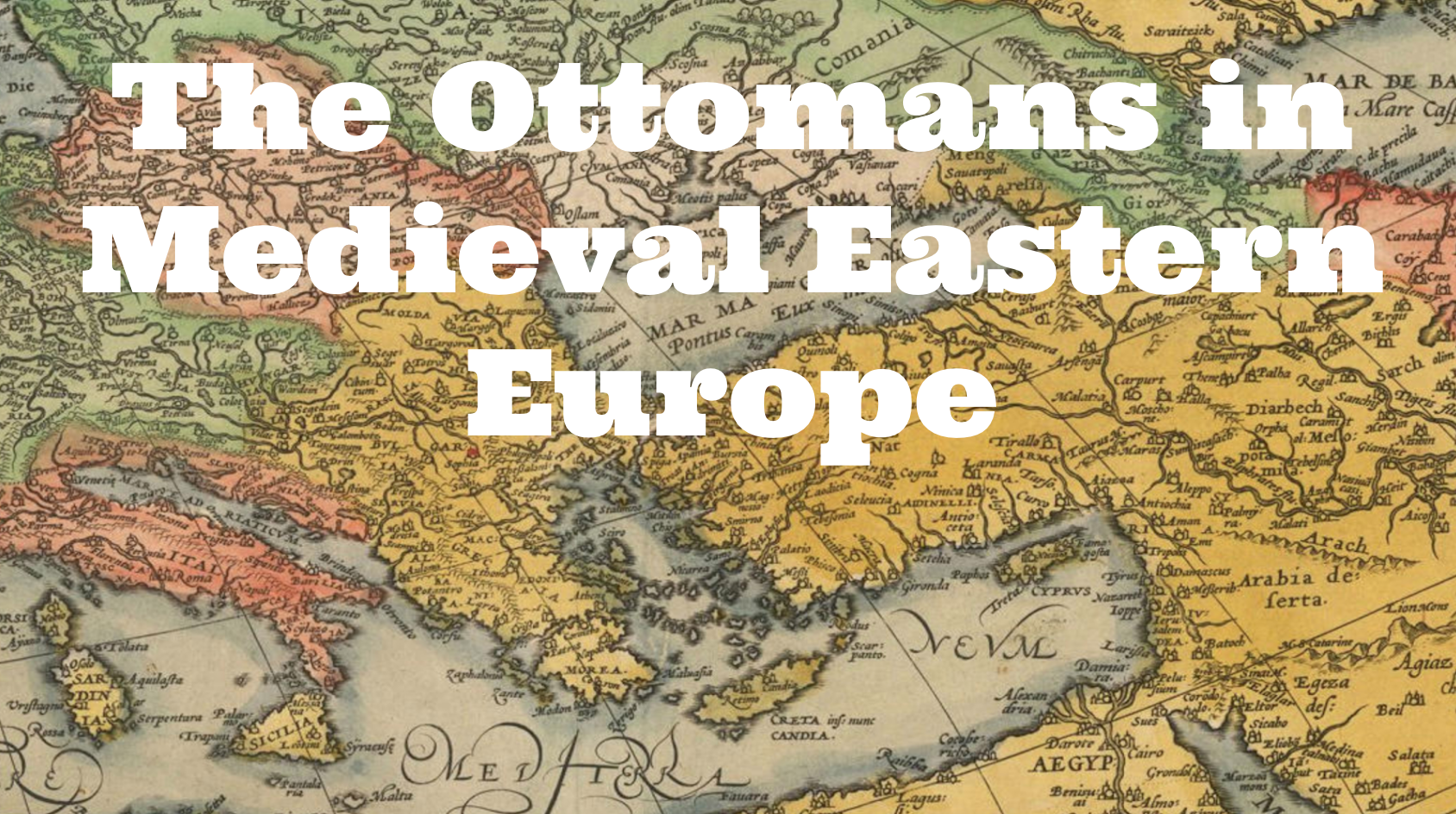

Summary | The Late Middle Ages in Eastern Europe

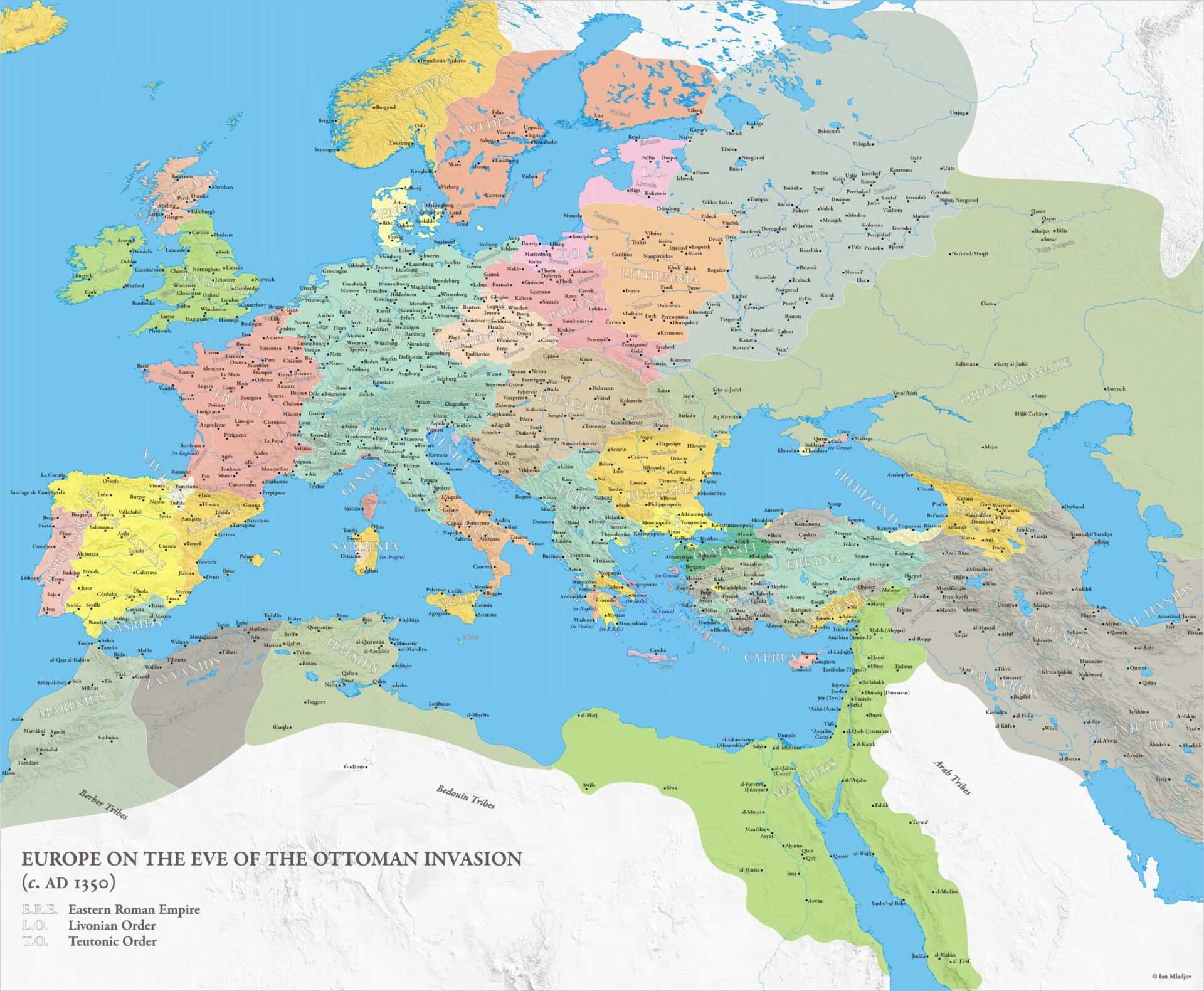

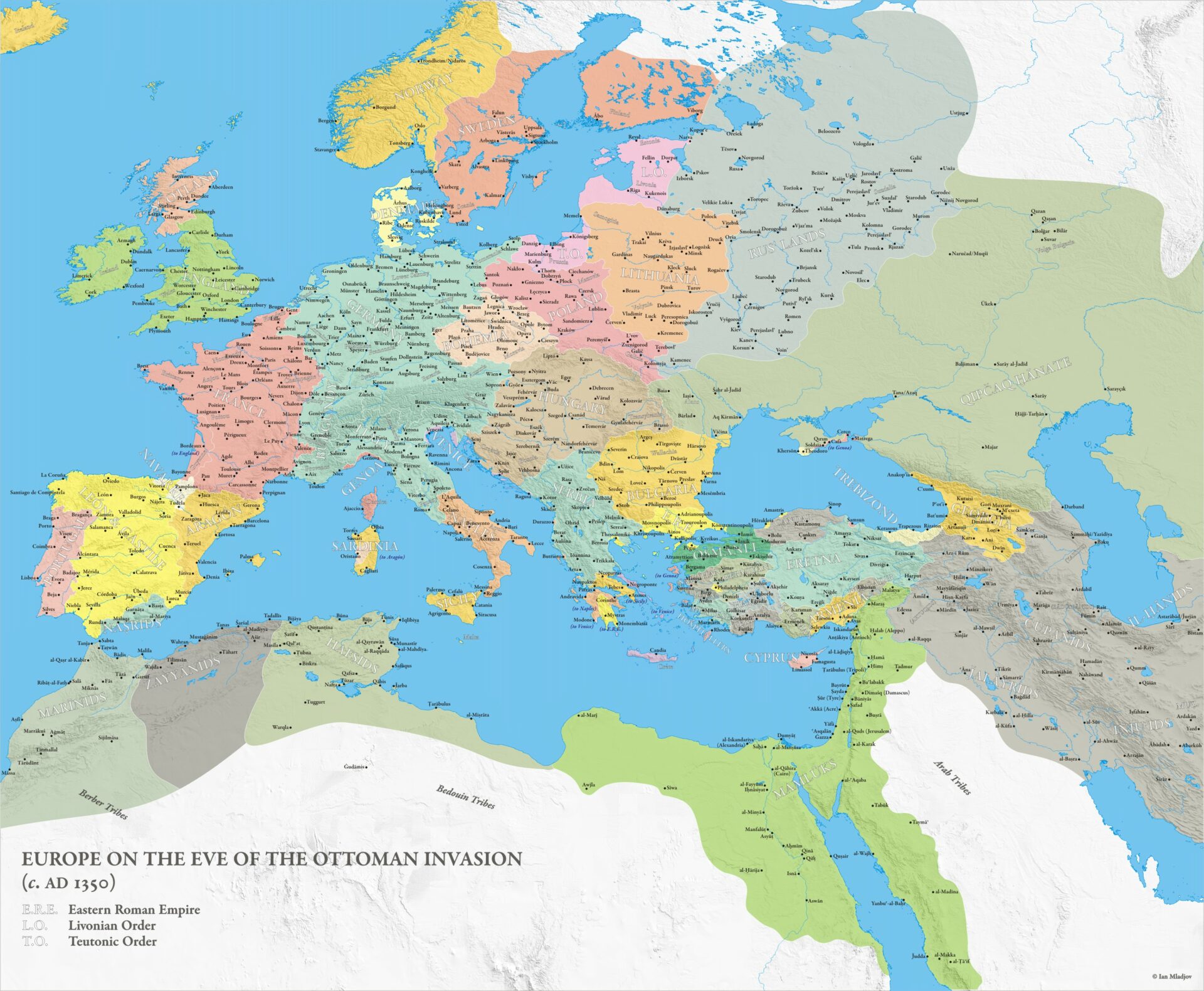

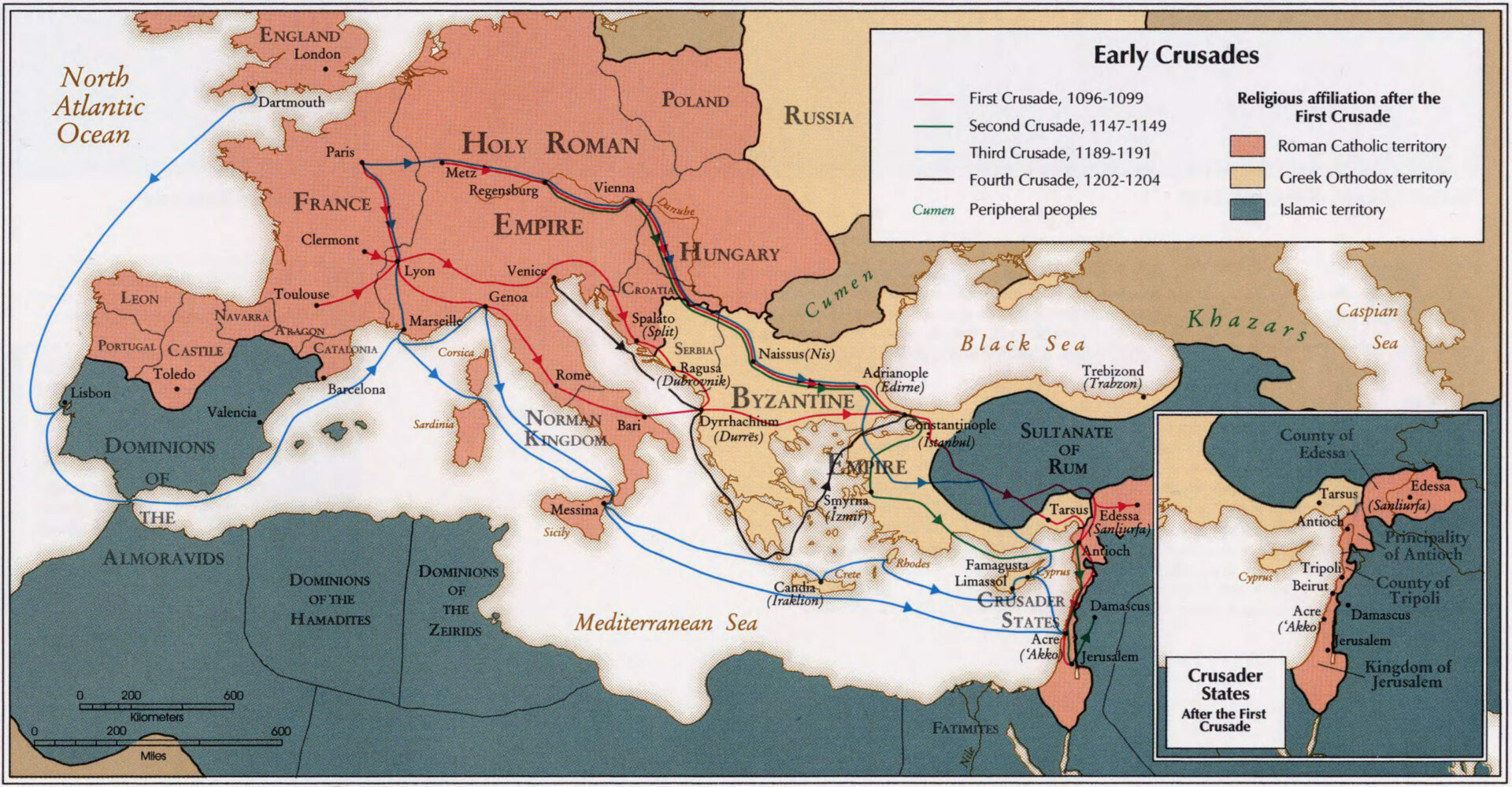

By the late eleventh century, instability in the Muslim and Byzantine empires and the expansion of the Seljuk Turks had made pilgrimages to Palestine unsafe for Christians. When Byzantine envoys asked Pope Urban II for military aid against the Seljuks, the pope responded by calling for a Crusade. Crusades, or holy wars supported by the papacy against the infidel, had been waged in Spain since the Muslim invasions of the eighth century.