Summary | The Modernization of Nations

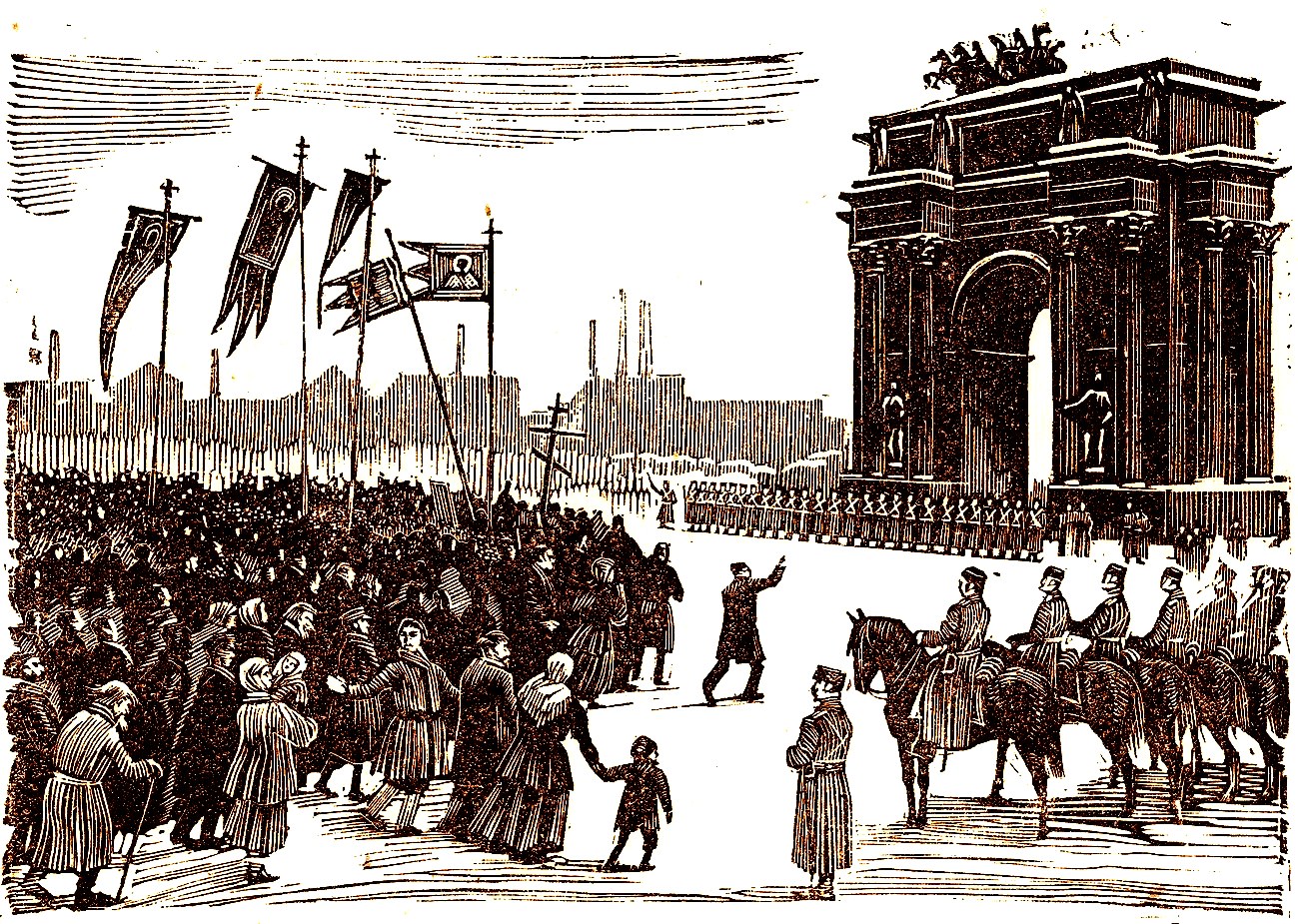

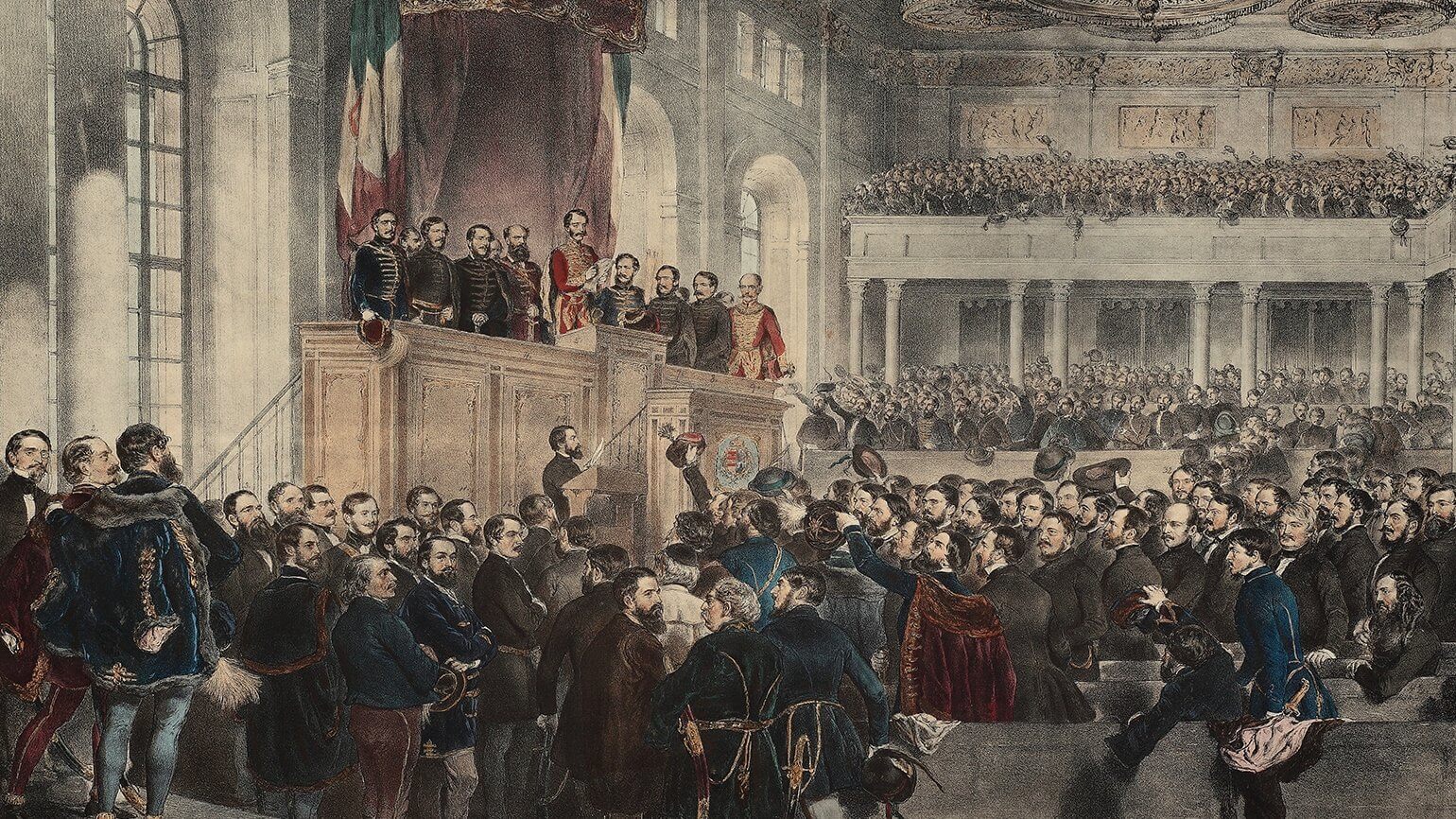

During the nineteenth century a sense of patrie, or commonality, brought the French together. A coup d’etat engineered by Louis Napoleon in 1851 ended the Second Republic and gave birth to the Second Empire.

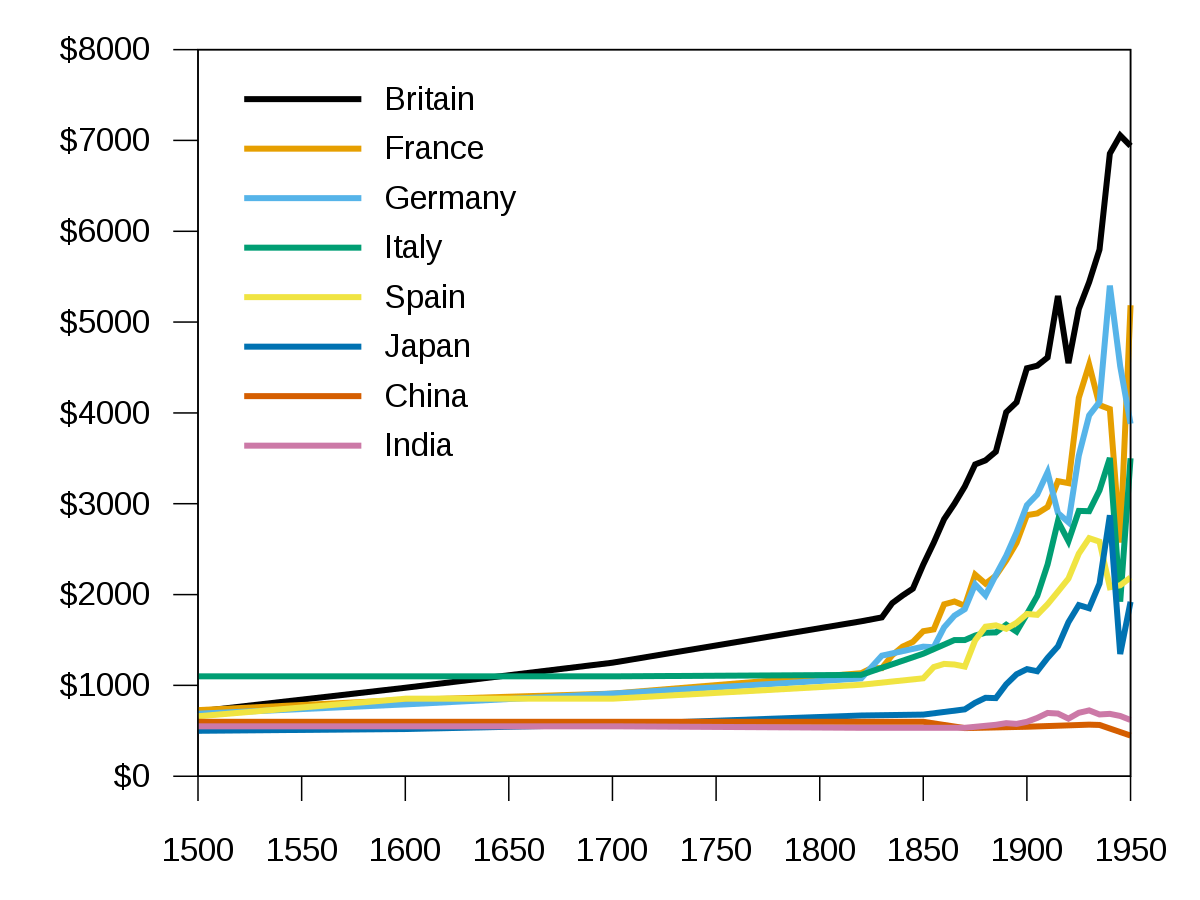

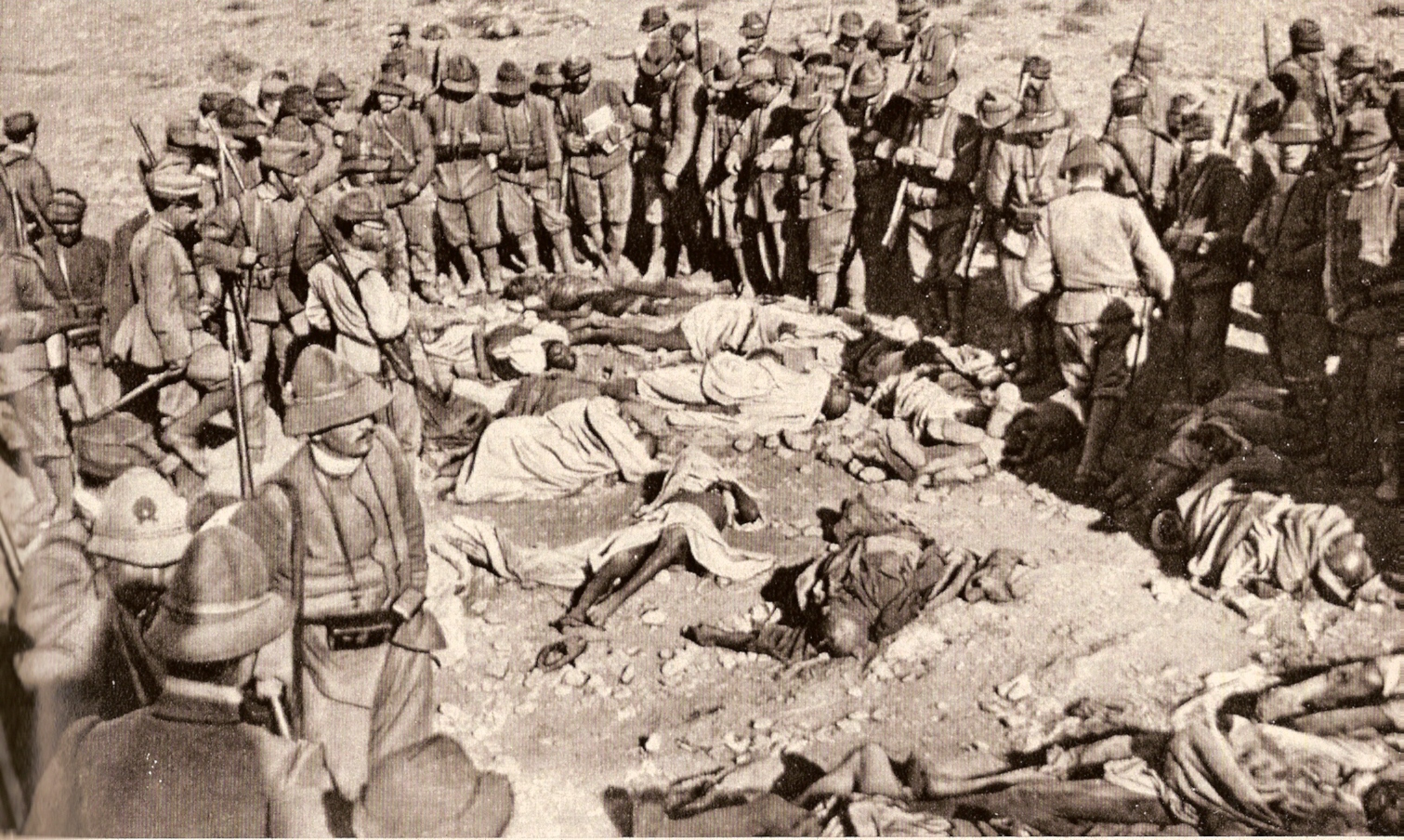

Napoleon III promised to reform but did little to improve the standard of living of the working class. Population expansion and industrial growth were smaller in France than in many other western European nations. The Franco-Prussian War ended the Second Empire.