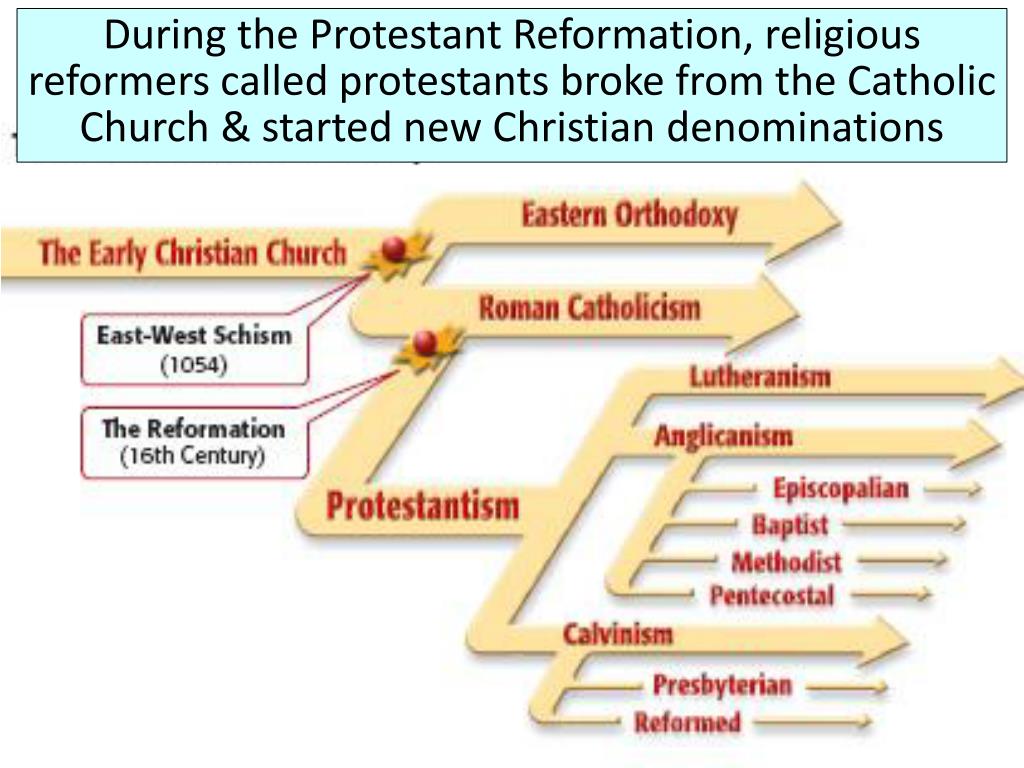

Summary | The Protestant Reformation

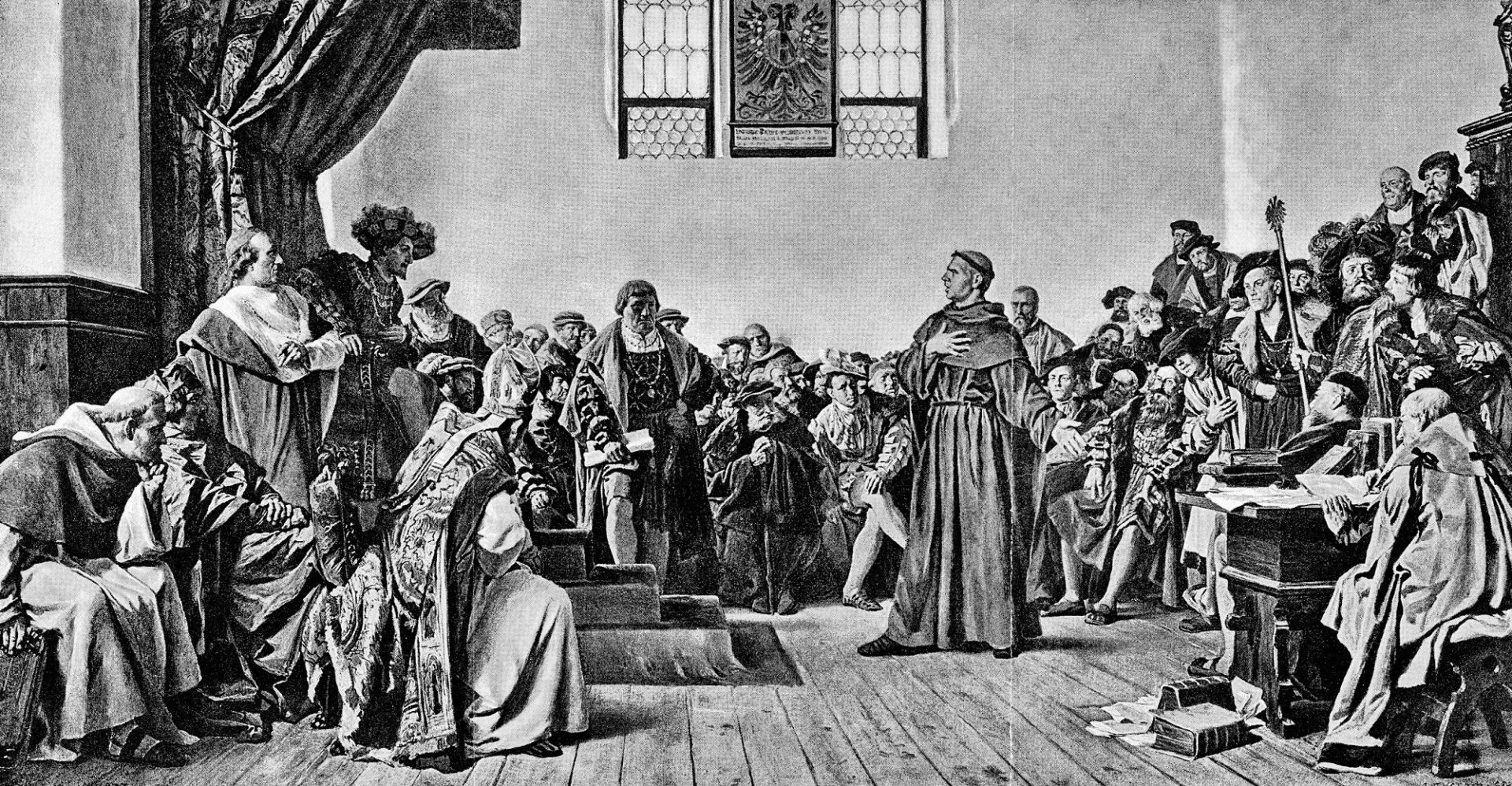

In 1517 Martin Luther touched off a revolution when he drew up Ninety-five Theses for debate. In them he questioned church practices, specifically the practice of granting indulgences—popularly believed to grant forgiveness of sin and remission of punishment. Luther himself had come to believe in the primacy of faith over good works and in the priesthood of individual believers.