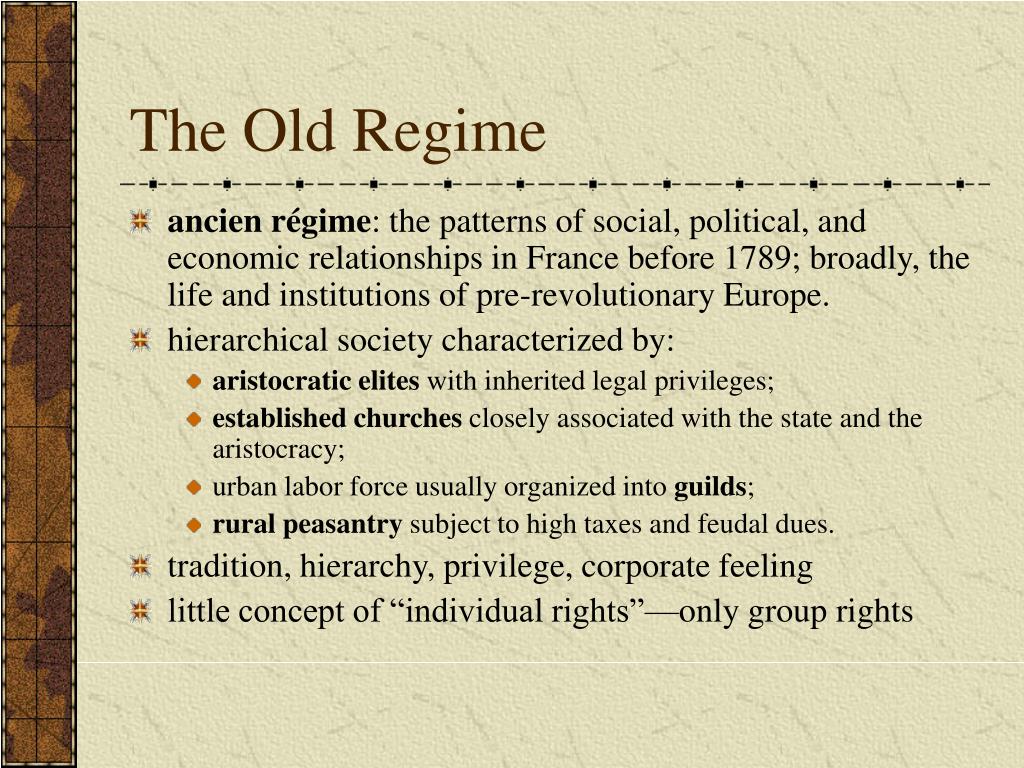

Summary | The Old Regimes

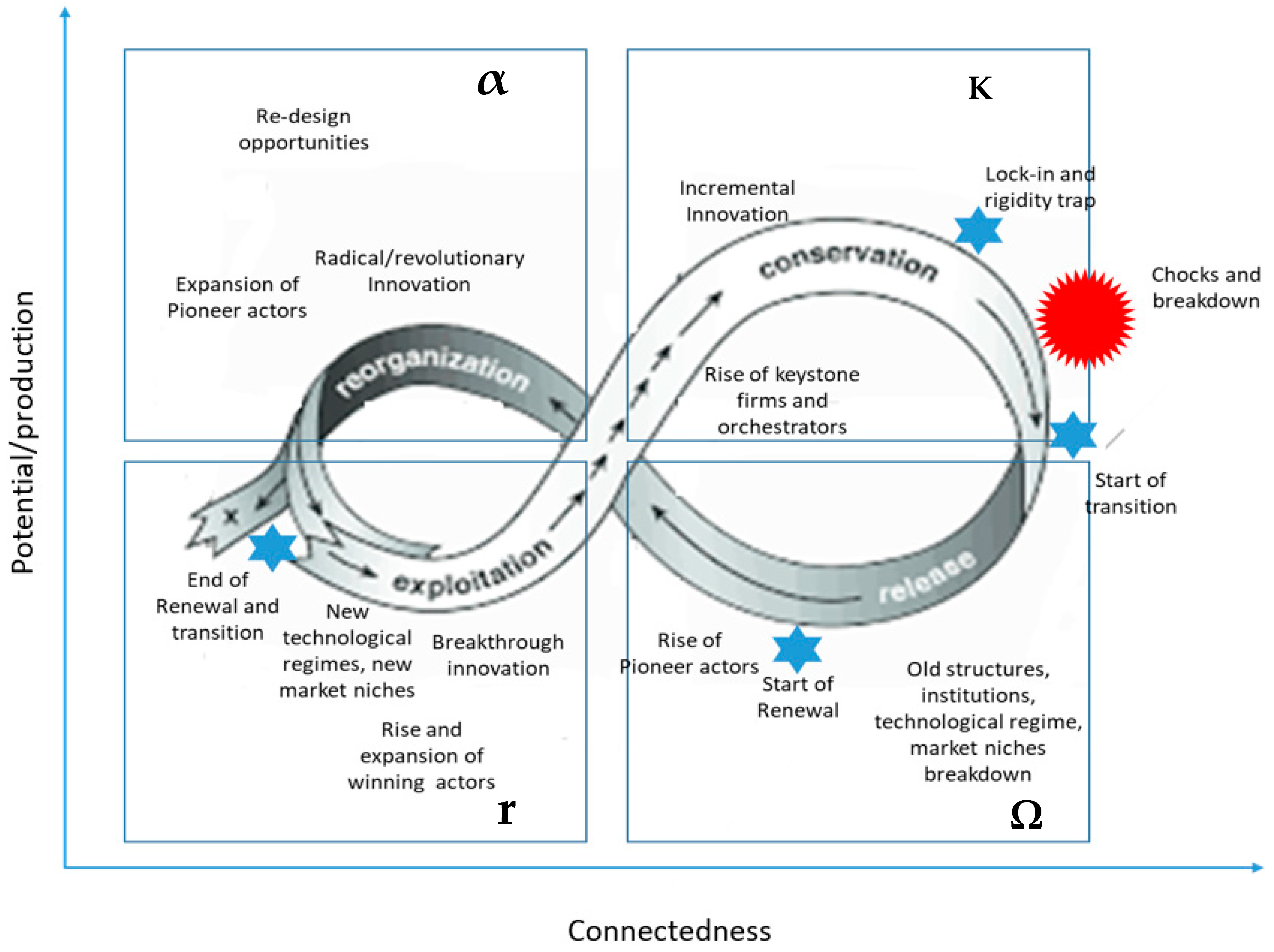

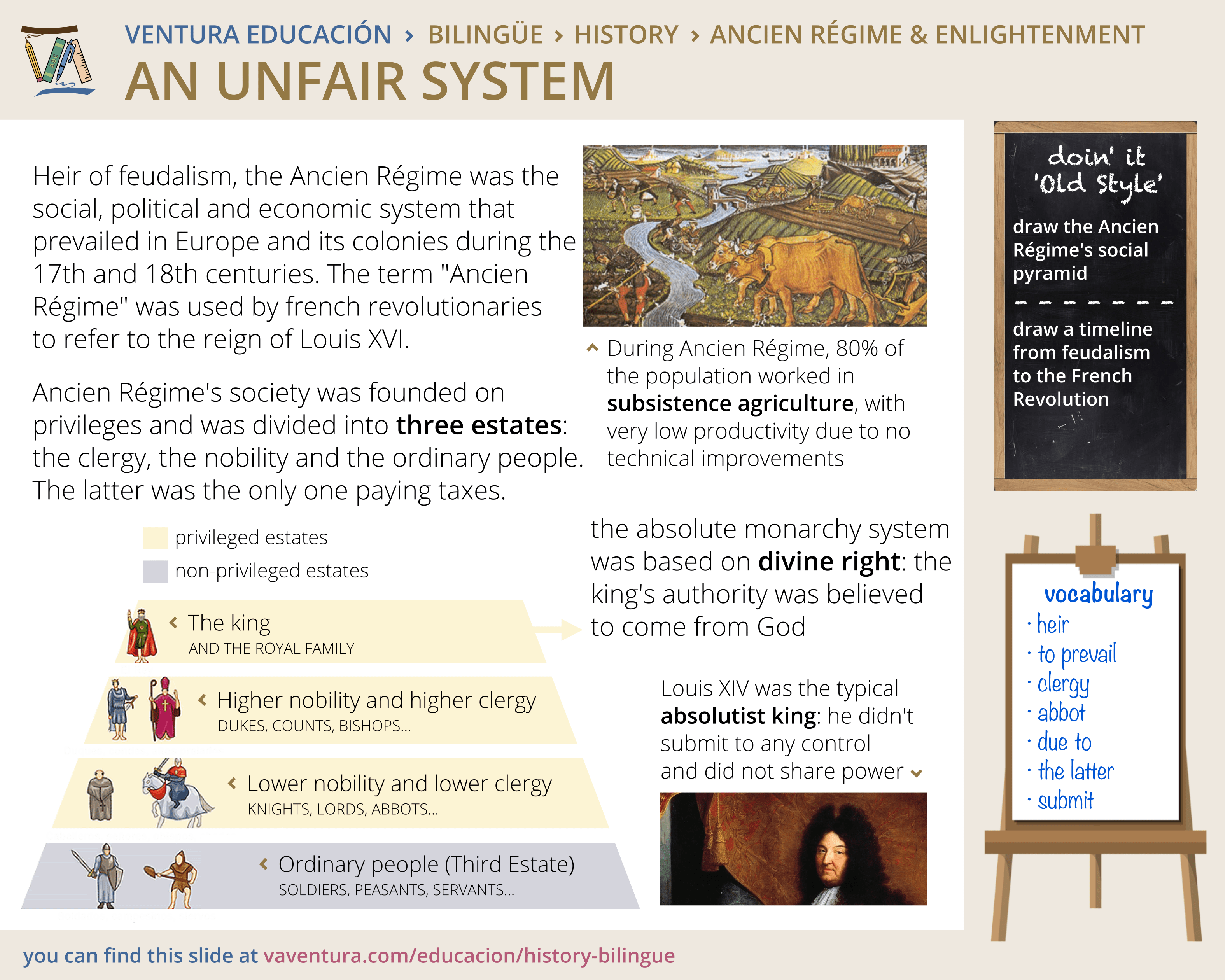

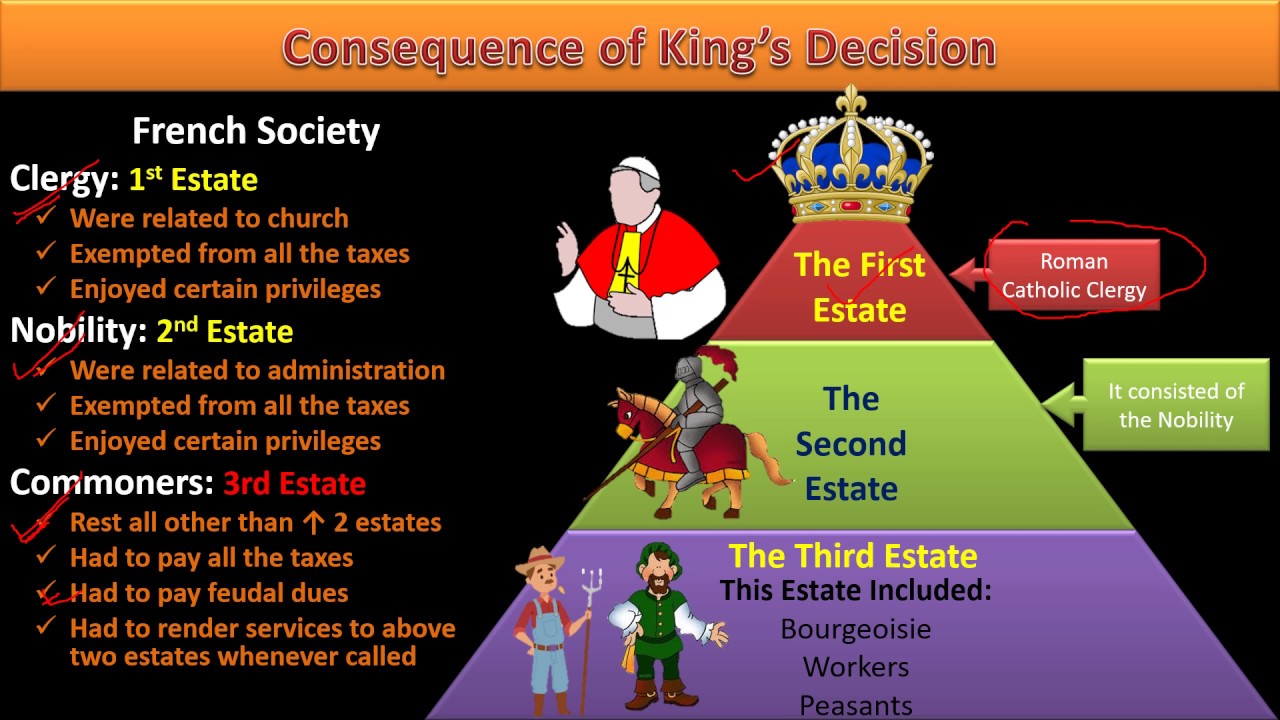

The Old Regime, the institutions that existed in France and Europe before 1789, exhibited features of both the medieval and early modern worlds. The economy was largely agrarian, but in western Europe serfdom had disappeared. The social foundations of the Old Regime were based on three estates. Increasingly, the economic, social, and political order of the Old Regime came under attack in the eighteenth century.