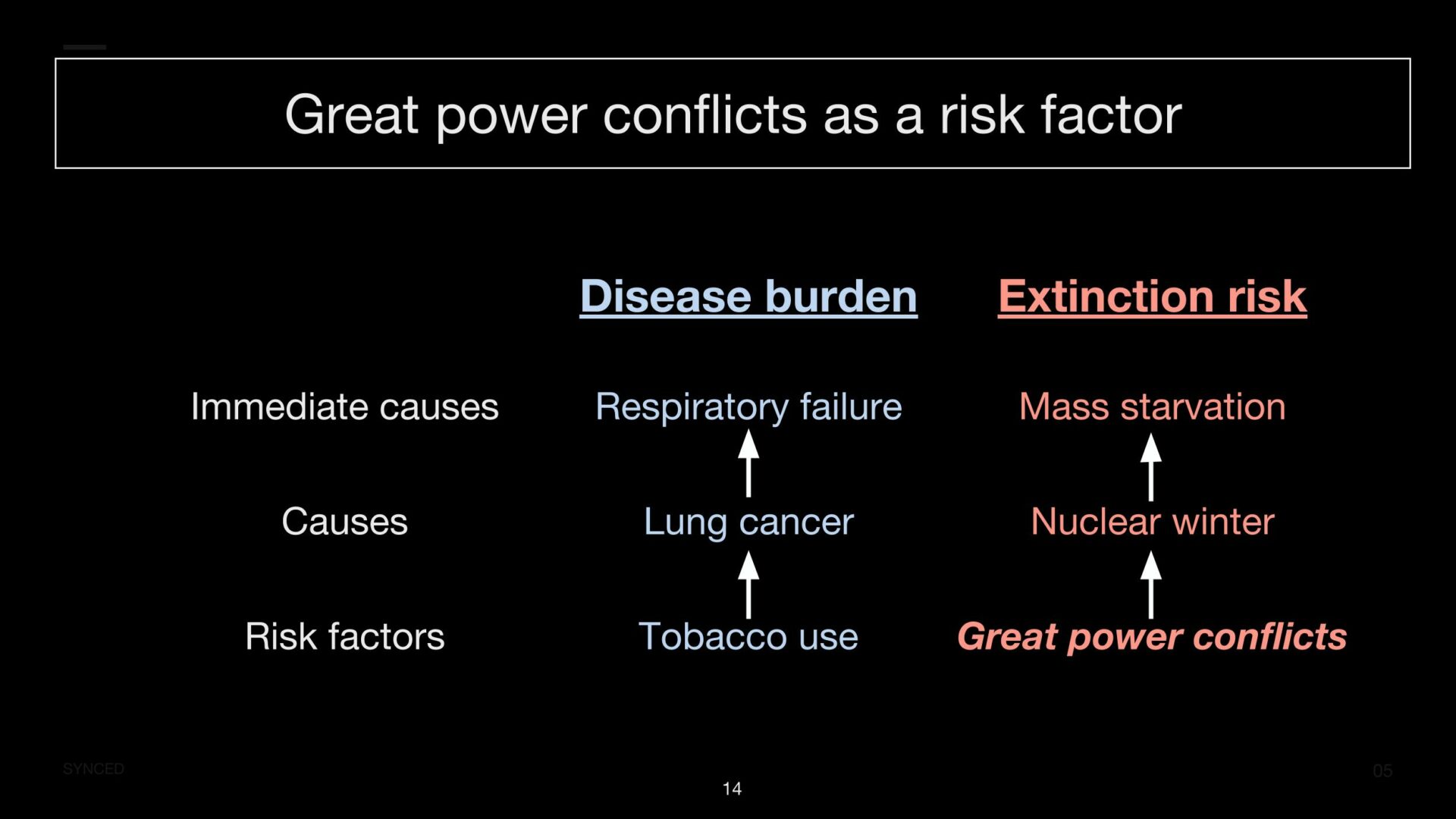

Summary | The Great Powers in Conflict

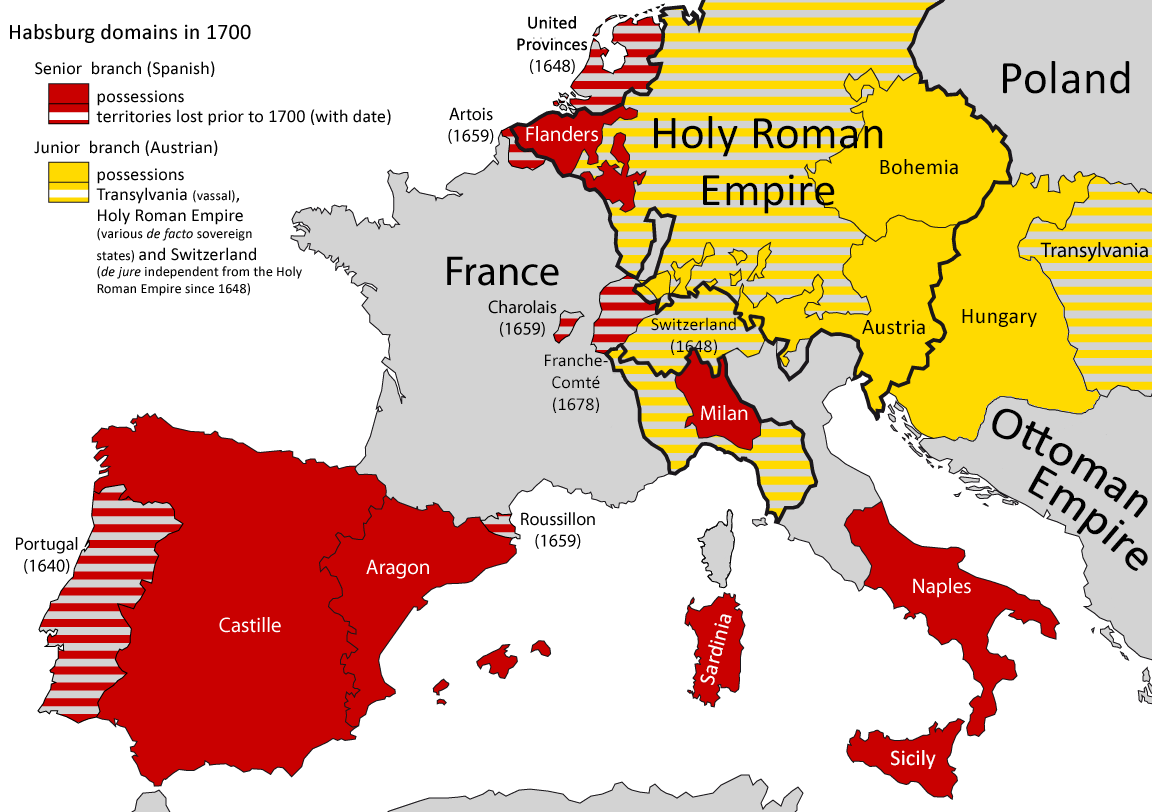

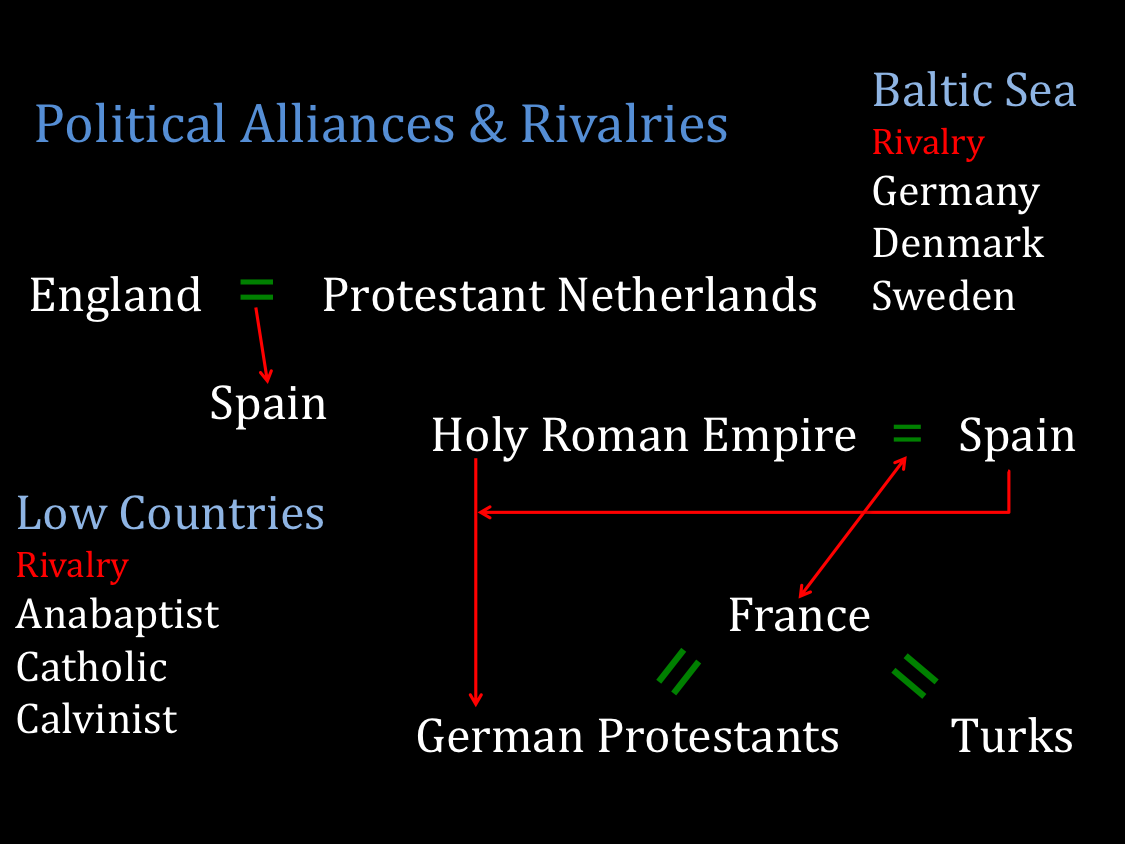

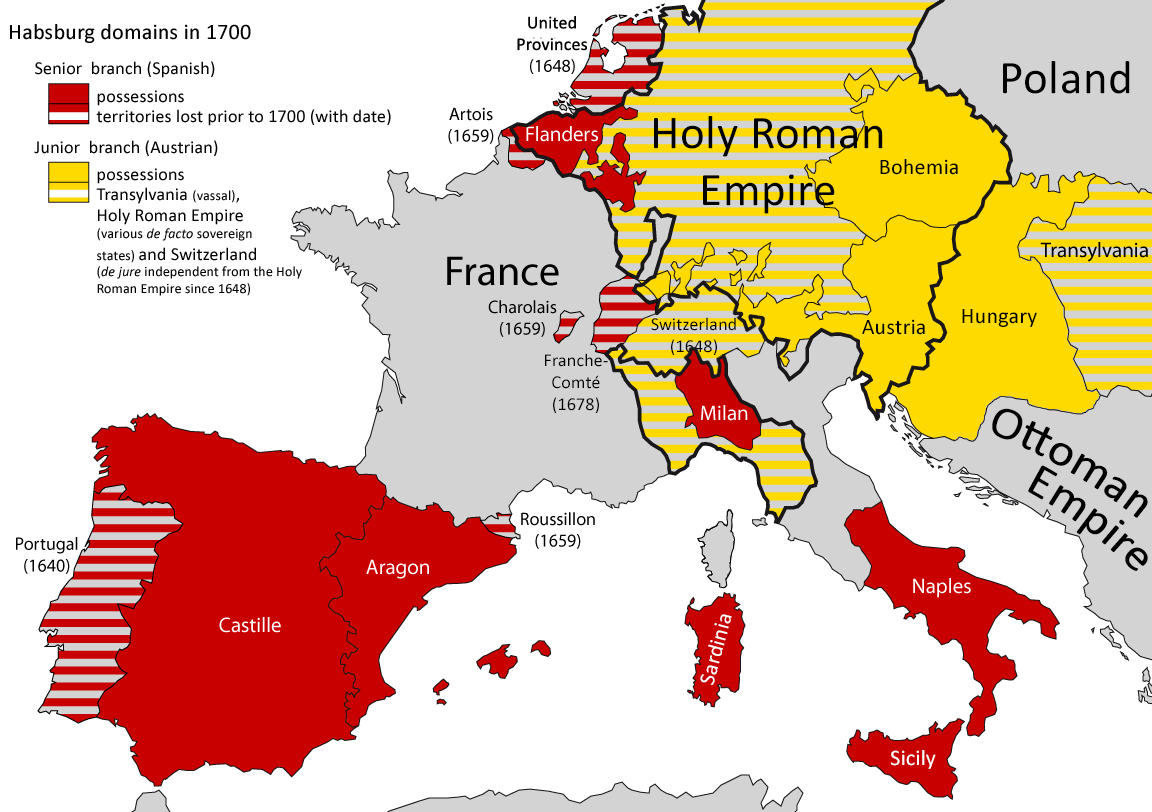

By the sixteenth century, changes in political, social, family, and economic structure were underway that marked the beginning of what historians call the modern period. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the modern state system took shape as well-organized states competed for power in western Europe.

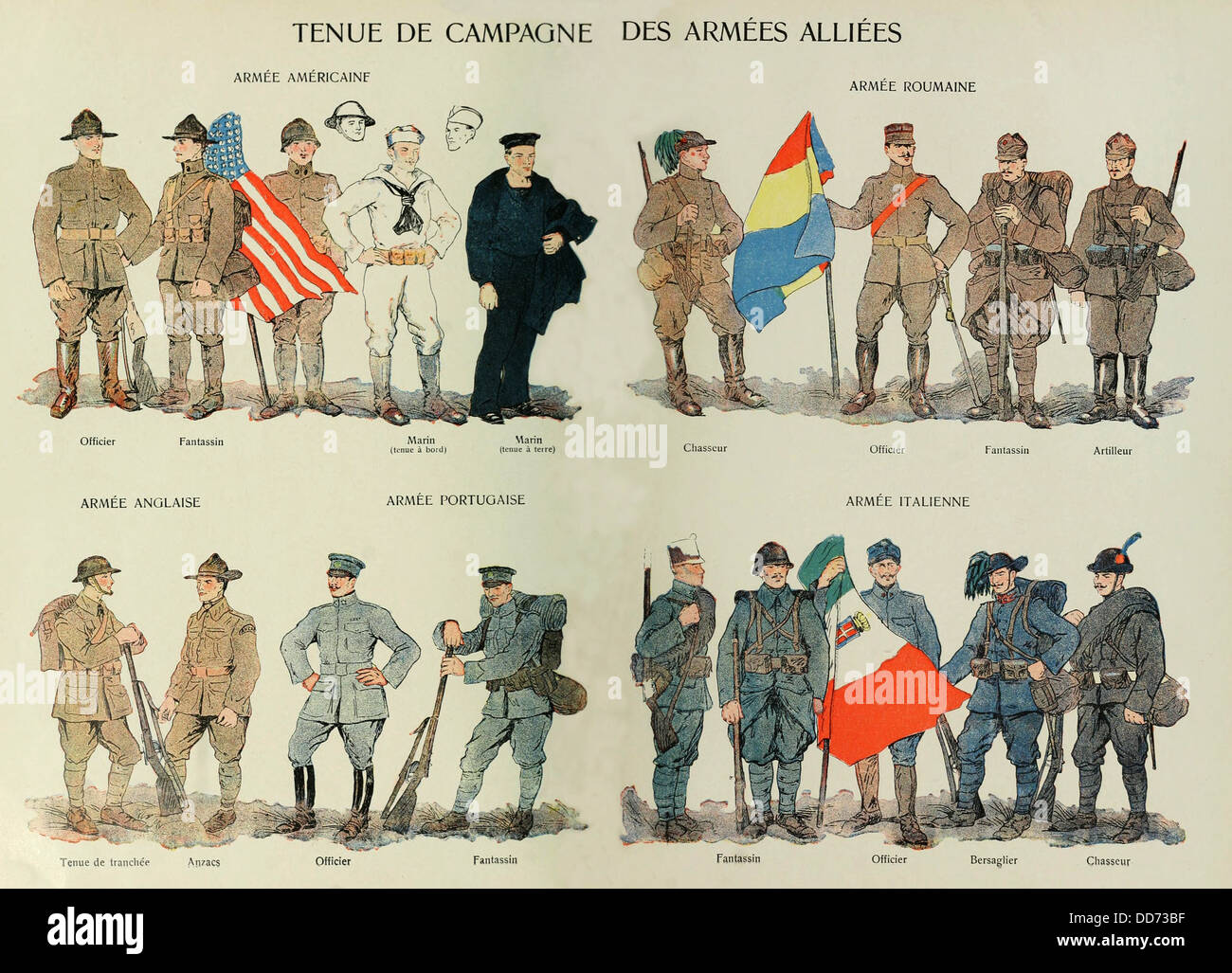

With the emergence of Spain, France, and England came the growth of national patriotism. European states developed diplomatic services and professional armies. The first modern navies were also built. Increases in population, trade, and prices fostered conditions that led to warfare.