A vigorous and ambitious monarch, King Christian IV sought to extend Danish political and economic power over northern Germany. To check the Danish invasion, the German Catholics enlisted the help of the private army of Albert of Wallenstein (1583-1634). Wallenstein recruited and paid an army that lived off the land.

He had bought huge tracts of Bohemian real estate confiscated from Czech rebels and was in essence a private citizen seeking to become a ruling prince. Though he never came close to success, his army was a major factor in the war at its most critical period. Together with the forces of the Catholic League, Wallenstein’s army defeated the Danes and invaded Denmark.

Then, at the height of success, the emperor Ferdinand and his advisers overreached themselves. In the Edict of Restitution (1629) they demanded the restoration of all clerical estates that had passed from Catholic to Lutheran hands since 1551. The Edict also affirmed the Augsburg exclusion of Calvinists and radical Protestants from toleration. The Treaty of Lubeck, two months later, allowed Christian IV to recover his Danish lands but exacted from him a promise not to intervene again in Germany.

Ferdinand’s heavy-handedness contrasted with Cardinal Richelieu’s handling of the Huguenots at the siege of La Rochelle, which ended in 1628. There, despite the unprecedented length and ferocity of the siege and the wide agreement that fallen cities could be sacked, the royal army was kept under absolute discipline and food was provided to the starving inhabitants of the city.

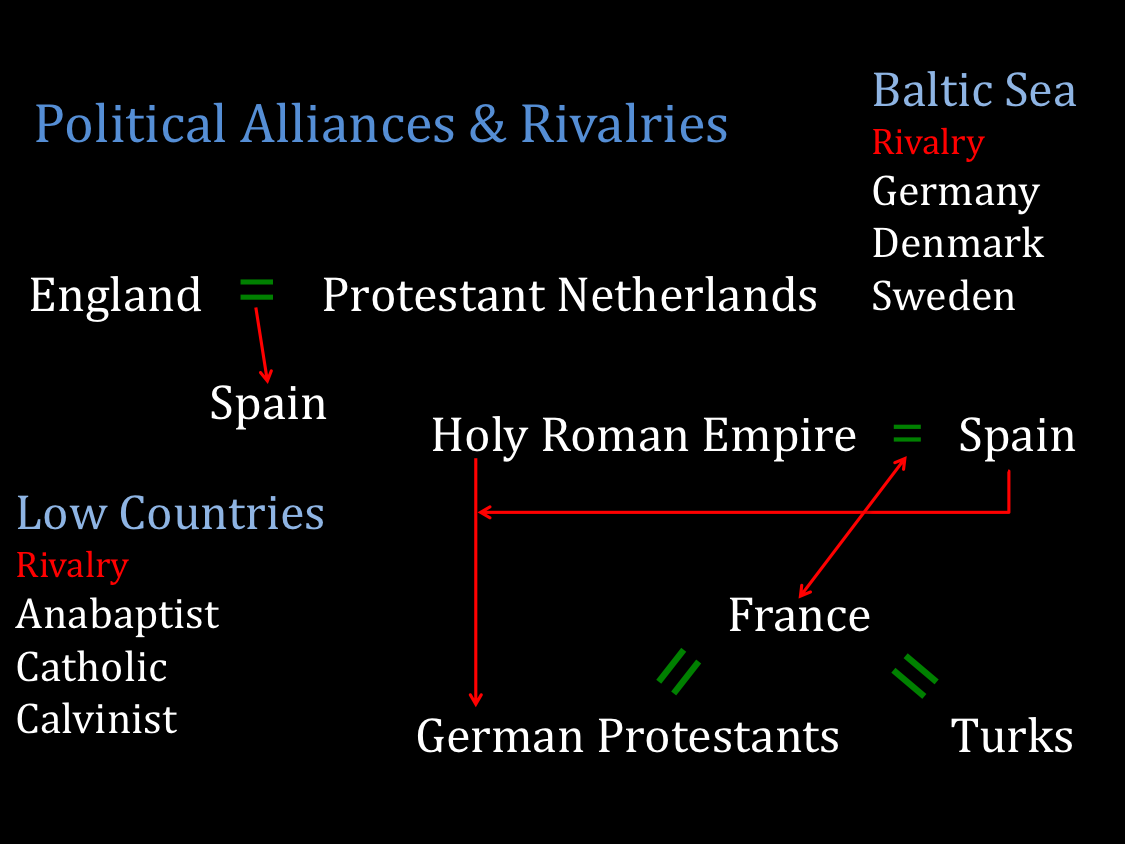

Richelieu acted with magnanimity, making it clear that while La Rochelle must abandon its political independence, and every church be returned to the Catholics, the price of heresy need not be paid in blood. What concerned Richelieu was maintaining a balance of power. The Habsburgs were now pressing into the Baltic, well beyond their spheres of influence, and although fellow Catholics, they were trespassers who ought to be forced to withdraw.

The more the emperor Ferdinand became indebted to the ambitious Wallenstein, the less he could control him. Wallenstein planned to found a new Baltic trading company with the remnants of the Hanseatic League, and by opening the Baltic to the Spaniards make possible a complete victory over the Dutch. Thus, when Ferdinand asked him for troops to use in Italy against the French, Wallenstein, intent on his northern plans, refused. Ferdinand dismissed Wallenstein, leaving the imperial forces under the command of the count von Tilly and of Maximilian of Bavaria, who had been alarmed by Wallenstein’s activities and was placated by his departure. If Ferdinand had also placated the Protestants by revoking the Edict of Restitution, peace might have been possible. But he failed to do so, and the war was resumed with Gustavus Adolphus as the Protestant champion.

Called the “Lion of the North,” Gustavus Adolphus (r. 1611-1632) was a much stronger champion than Christian of Denmark had been. Like Christian, he had ambitions for political control over northern Germany, and he hoped that Sweden might assume the old Hanseatic economic leadership. Gustavus brought a large well-disciplined army and added to it all the recruits, even prisoners, that he could induce to join him. Sharing the hardships of his troops, he usually restrained them from plunder. Richelieu agreed to subsidize his forces, and Gustavus agreed not to fight against Maximilian and to guarantee freedom of worship for Catholics. The Protestant electors of Brandenburg and Saxony mobilized, both to revive the Protestant cause and to protect the Germans against the Swedes.

German Protestant hesitation ended after a Catholic victory that probably did more to harm the Catholic cause than a defeat—the fall and sack of Magdeburg, a great symbol of the Protestant cause. Stormed by the imperialists in May 1631, it was almost wholly destroyed by fire and pillage. Each side sought to blame the sack on the other and sued the printing press to enlist public opinion in its cause throughout Europe. The Protestants accused the imperial commander-in-chief, Tilly, of planning the destruction of the city and its inhabitants—an accusation from which most historians absolve him, for the imperial troops clearly got out of hand. The Catholics countered by accusing the Protestants of setting the fires themselves. But in the long run, as the outpourings of the press took effect, the Protestant cause was strengthened.

The Protestant electors of Brandenburg and Saxony now allied themselves with Gustavus. In September 1631 Gustavus defeated Tilly. Combined with a defeat of the Spaniards off the Dutch coast, this turned the tide against the Habsburgs. The Saxons invaded Bohemia and recaptured Prague in the name of Frederick of the Palatinate, while Gustavus invaded the Catholic lands of south-central Germany, achieving an alliance of many princes and free cities. In the crisis, Ferdinand turned again to Wallenstein.

Gustavus was planning to reorganize all Germany, to unite the Lutheran and Calvinist churches, and to become emperor—aims opposed by all the German princes, Catholic and Protestant alike. In the face of his ambitions, his allies proved untrustworthy, and his enemies, Maximilian and Wallenstein, drew together. In November 1632 the Swedes defeated Wallenstein at Liitzen, but Gustavus Adolphus was killed.

Peace might now have been possible, yet the fighting continued. Richelieu preferred war to further advance French aims in the Rhineland; the Swedes needed to protect their heavy investment and come out of the fighting with some territory; the Spaniards hoped that Gustavus’s death meant that the Habsburg cause could be saved and the Dutch at least defeated.

As Wallenstein negotiated with the enemies of the Empire, hoping the French would recognize him as king of Bohemia, his army began to fade away, and he was again dismissed by the emperor Ferdinand. In February 1634 an English mercenary in the imperial service murdered Wallenstein and won an imperial reward. In September 1634 the forces of Ferdinand defeated the Protestants.