Summary | The Greeks

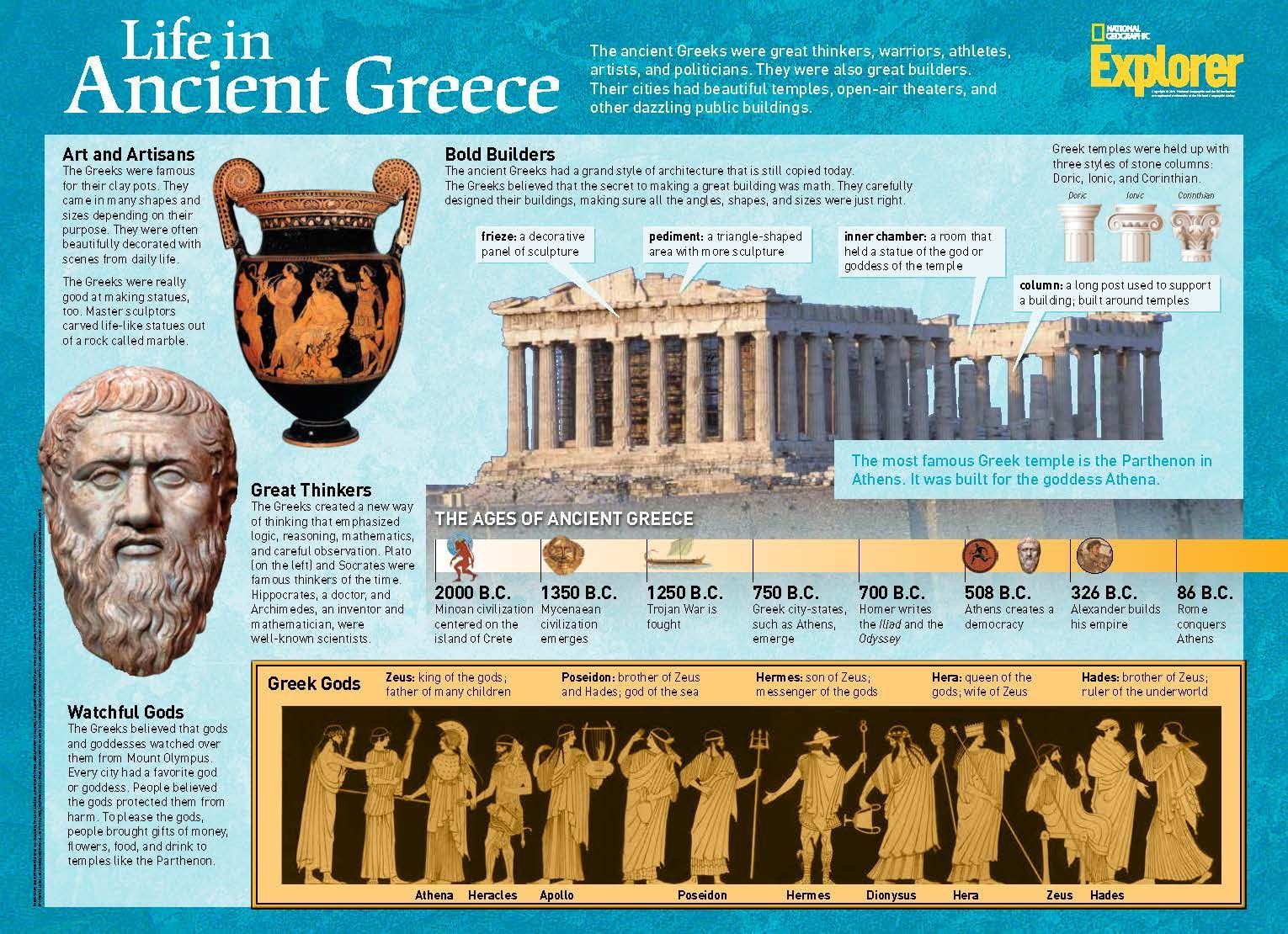

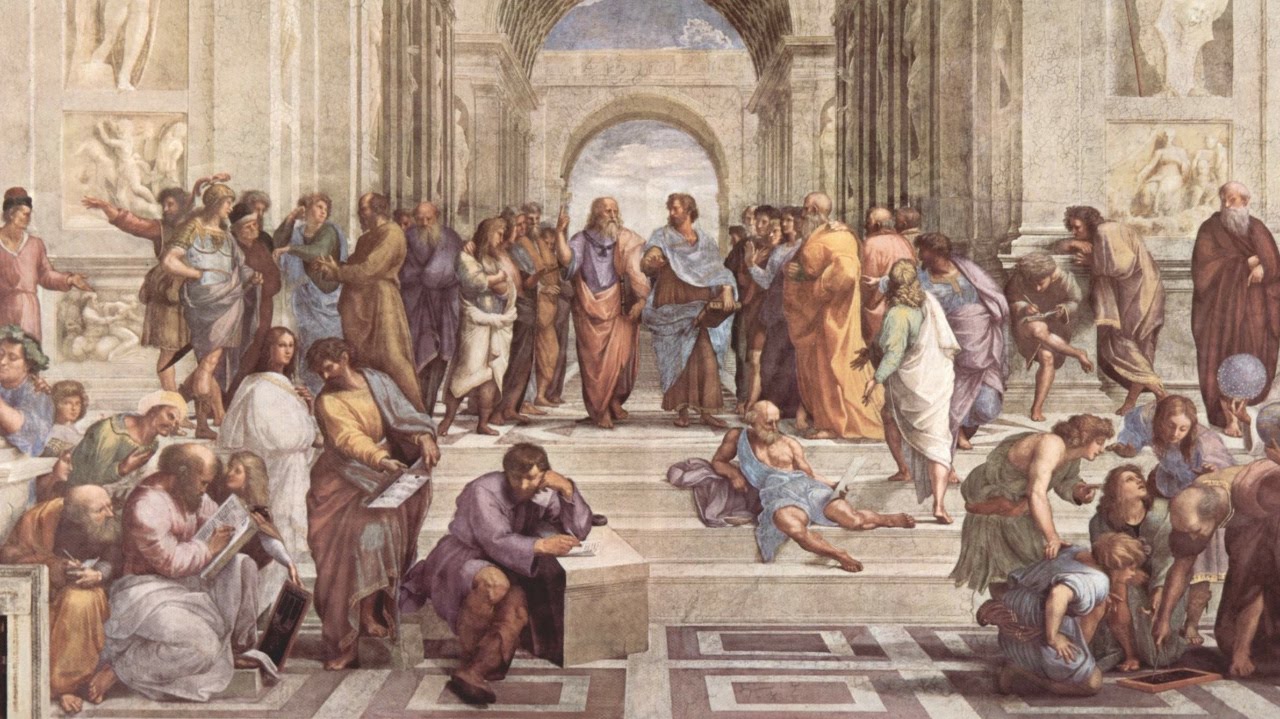

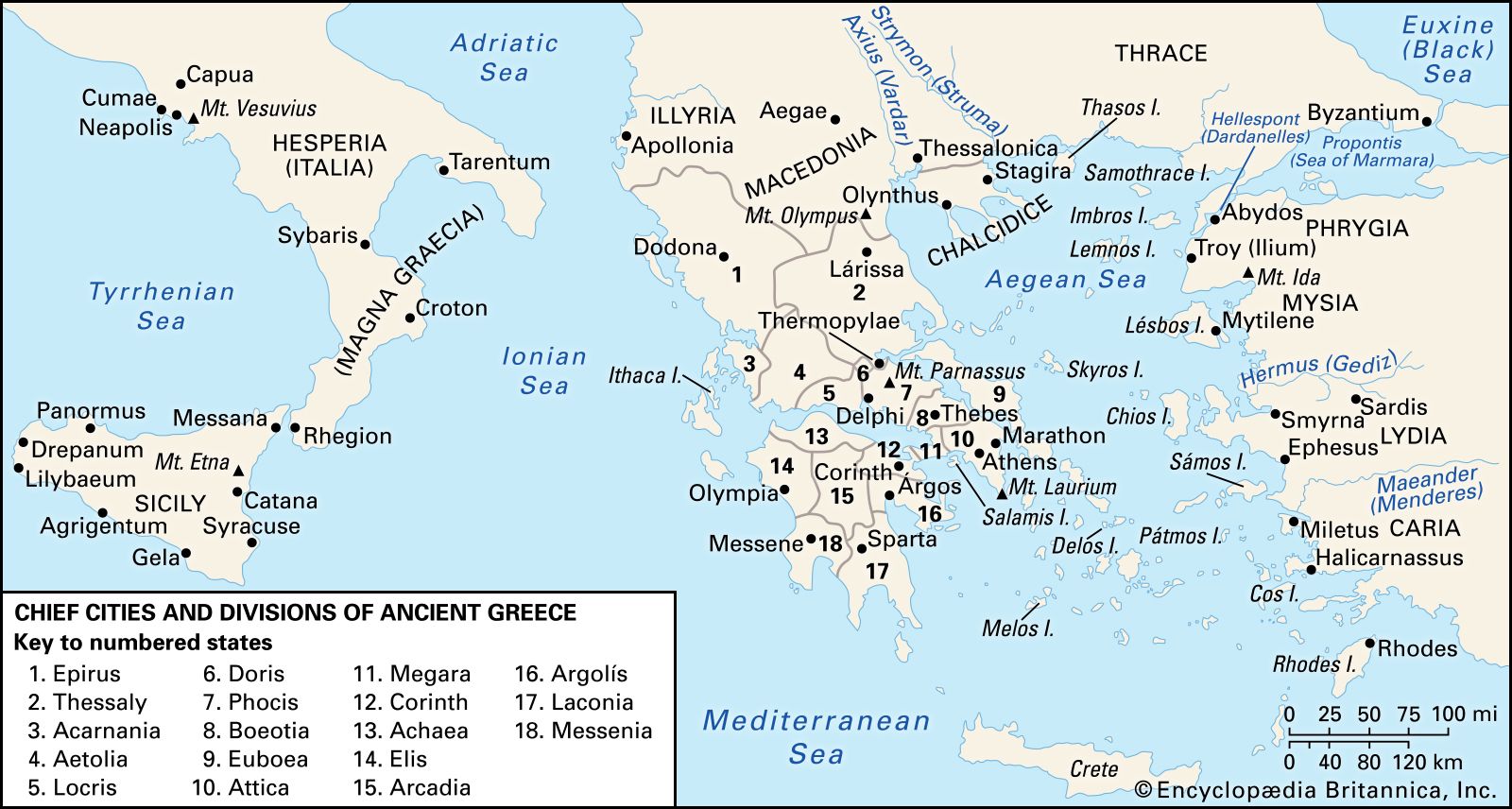

The Greeks are the first ancient society with which modern society feels an immediate affinity. We can identify with Greek art, Greek politics, Greek curiosity, and the Greek sense of history. The polis, roughly translated as the city-state, was the prevailing social and political unit of ancient Greece. Athens and Sparta were the two most significant poleis.

Sparta was a conservative military oligarchy ruled jointly by two kings and a council of elders. It had an excellent army, but its society was highly regimented. Sparta produced little of artistic or cultural importance.