For Calvinists the main theological concern was the problem of predestination against free will. The problem arose from the concept that God is all-powerful, all-good, all- knowing; this being so, he must determine all that happens, even willing that the sinner must sin. For if he did not so will, a person would be doing something God did not want, and God would not be all-powerful. There is a grave difficulty here. If God wills that the sinner sin, the sinner cannot be blamed for it. Logical argument appeared to be at a dead end.

Theologians preserve the moral responsibility of the individual by asserting the profound distance between God and humanity, a distance that faith alone can bridge. This means that for a person to claim that whatever is done is what God wants done is to make a presumptuous claim to knowing God’s will. Petty human understanding is never on a par with God’s; a person can never be certain of what God wants done; therefore, one should look for signs of God’s intentions.

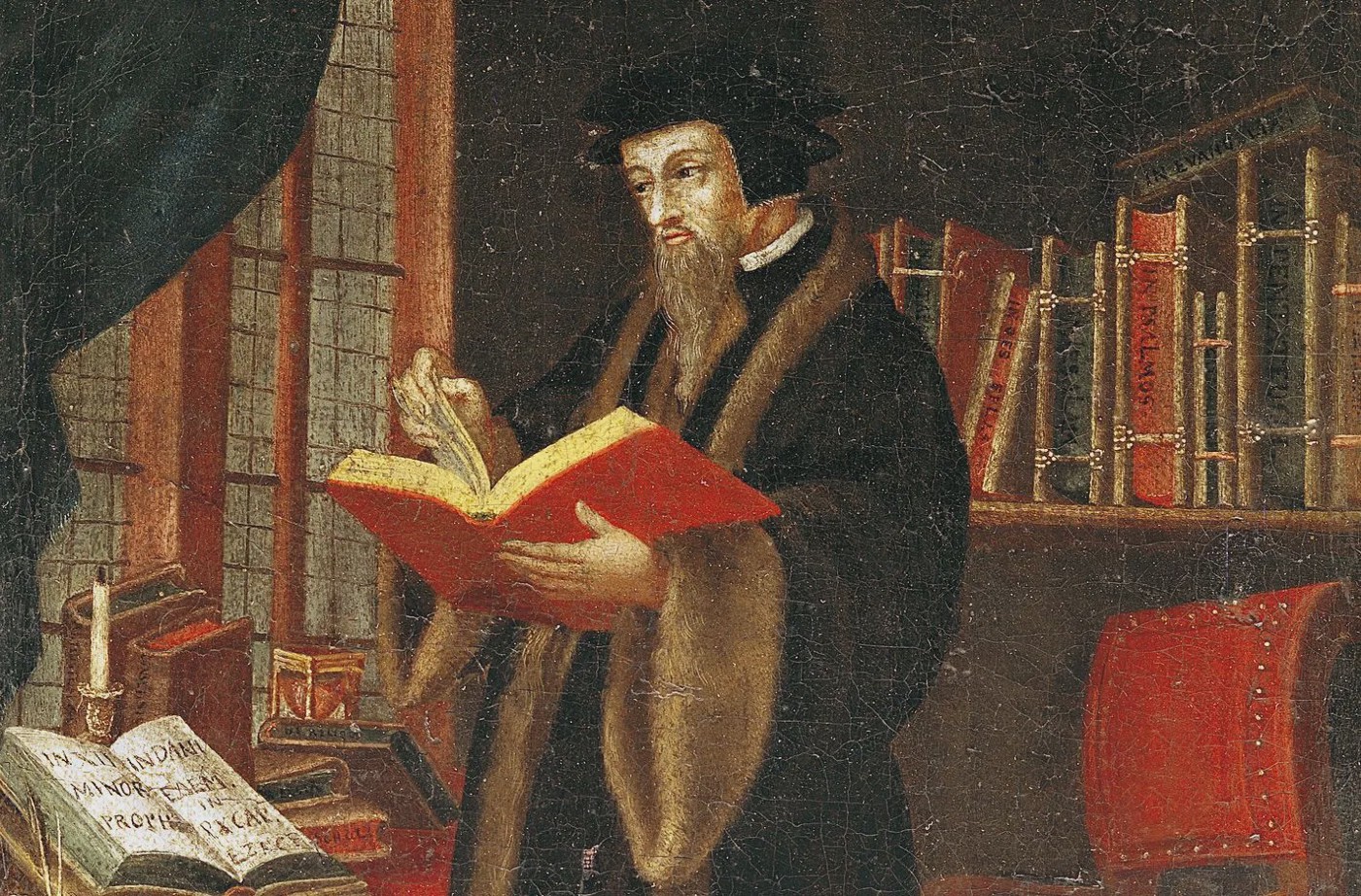

Such signs are found in Christian tradition and history. Calvin himself would have reached the same conclusion. But he was a logician. Both his temperament and his environment led him to reject what he believed to be the Catholic emphasis on easy salvation. He emphasized the hard path of true salvation, the majesty of God, and the insignificance of humanity; therefore he evolved an extreme form of the doctrine of predestination.

In Calvin’s system Adam’s original sin was unforgivable. God, however, in his incomprehensible mercy, sent Jesus Christ to this earth and let him die on the cross to make salvation possible for some—but not all or even most—of humanity. Only the elect could attain salvation, and that through no merit of their own. The elect were saved only through God’s free and infinite grace, by means of which they were given the strength to gain salvation. The elect tend to behave in a certain way, an identifiable way, a way that could be called “puritanical.”

Where the Calvinists were in complete control of an area (as in sixteenth-century Geneva) or in partial control of larger areas (as in England, Scotland, the Netherlands, or Puritan Massachusetts), they censored, forbade, banished, and punished. Particularly in Geneva, the local Catholic tradition of scrutinizing the morals of the populace continued on an intensive scale.

Every week a consistory composed of pastors and lay elders appointed by the city council passed judgment on all accused of improper behavior. The members of the Geneva consistory and other representatives of the Puritan spiritual police saw themselves as God’s agents, doing God’s work. Paradoxically, these firm believers in the inability of human efforts to change anything worked most ardently to get people to change their behavior.

The Calvinists did not seek to eliminate physical pleasures, but sought rather to select among worldly desires those that would further salvation, and to curb or suppress those that would not. They believed that Satan fostered human pleasures—music, dancing, gambling, fine clothes, drinking, play going, and fortune telling, among others. Although the Calvinists did not hold that all sexual intercourse was sinful, they believed that God provided sex to continue life and not to give pleasures; such pleasures were all the more dangerous since they might lead to sex outside of marriage, which was a very great sin.

Calvinism appeared in pure or diluted form in many sects: Presbyterian and Congregational in Britain, Reformed on the Continent. It influenced even the Anglicans and the Lutherans. Theologically its main opponent was a system of ideas called Arminianism, from Jacobus Arminius (1560-1609), a Dutch professor at Leiden. Arminius held that election and damnation were conditional in God’s mind—not absolute as Calvin had maintained—and that therefore what a person did on earth could change that person’s fate.

Where it became the established state church—in Geneva, in the England of the 1650s, in Massachusetts, for instance—the Calvinist church ran or tried to run the state. However, this theocracy was never fully realized, even in Geneva, where the city council refused to surrender all of its authority.

Where Calvinism had to fight to exist, it preached and practiced an ardent denial of the domination of the state over the individual. Later generations turned these affirmations of popular rights to the uses of their own struggles against both kings and churchmen.