By the fourteenth century the Ottoman Turks had begun to press against the borders of Byzantine Asia Minor. Economic and political unrest led the discontented population of this region to prefer the Ottomans to the harsh and ineffectual Byzantine officials. Farmers willingly paid tribute to the Turks, and as time went on many of them were converted to Islam to avoid payment. They learned Turkish and taught the nomadic Turkish conquerors the arts of a settled agricultural life.

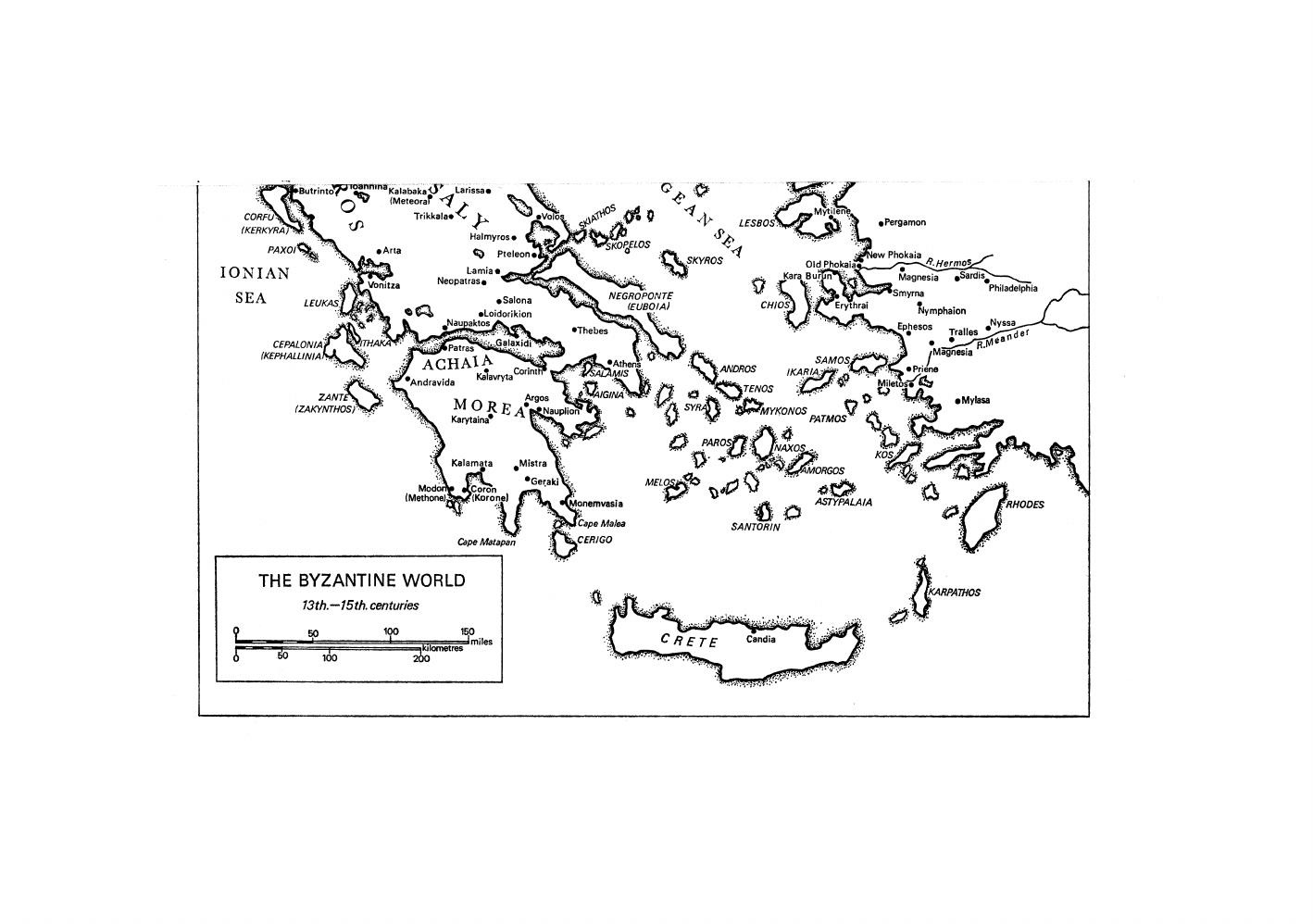

Having absorbed the Byzantine territories in Asia Minor, the Turks built a fleet and began raiding in the Sea of Marmora and the Aegean. In 1354 one of the rivals for the Byzantine throne allowed them to establish themselves in Europe. Soon they had occupied much of Thrace. In 1363 they moved their capital to Adrianople, well beyond the European side of the Straits. Constantinople was now surrounded by Turkish territory and could be reached from the West only by sea. To survive it all, the later emperors had to make humiliating arrangements with the Turkish rulers.

Although the Byzantine Empire lasted to 1453, its survival was no longer in its own hands. The Turks chose to attack much of the Balkan region first, conquering the Bulgarian and Serbian states in the 1370s and 1380s. A French and German “crusade” against the Turks was wiped out at Nicopolis on the Danube in 1396.

But further Turkish conquests were delayed for half a century when a new wave of Mongols under Timur the Lame (celebrated in literature as Tamerlane, c. 1336-1405) emerged from central Asia in 1402 and defeated the Ottoman armies at Ankara. Like most Mongol military efforts, this proved temporary, and the Ottoman armies and state recovered.

In the 1420s and 1430s the Turks moved into Greece. The West, now thoroughly alarmed at the spread of Turkish power in Europe, tried to bolster the Byzantine defenses by proposing a union of the Eastern and Western churches in 1439 and by dispatching another “crusade,” this time to Bulgaria in 1444. Both efforts proved futile.

With the accession of Muhammad II (also called Mehmed the Conqueror) to the Ottoman throne in 1451 (r. to 1481), the doom of Constantinople was sealed. New Turkish castles on the Bosporus prevented ships from delivering supplies to the city. In 1453 strong forces of troops and artillery were drawn up in siege array, and the Turks even dragged a fleet of small boats uphill on runners and slid them down the other side into the Golden Horn itself. The last emperor, Constantine XI (r. from 1448), died bravely defending the walls against the Turkish attack.

On May 29, 1453, with the walls breached and the emperor dead, the Turks took the city. Muhammad II gave thanks to Allah in Hagia Sophia; thenceforth, it was to be a mosque. Shortly thereafter, he installed a new Greek patriarch and proclaimed himself protector of the Christian church. On the whole, during the centuries that followed the Orthodox church accepted the sultans as the secular successors to the Byzantine emperors.