Moscow lay near the great watershed from which the Russian rivers flow north into the Baltic or south into the Black Sea. It was richer than the north, could provide enough food for its people, and had flourishing forest industries. Thus, when the Tatar grip relaxed and trade could begin again, Moscow was advantageously located. Moreover, Moscow was blessed with a line of remarkably able princes.

They married into powerful families, acquired land by purchase and by foreclosing mortgages, and inherited it through wills. They scored the first victories over the Tatars and could truthfully claim to be the champions of Russia. Finally, the princes of Moscow secured the support of the Russian church. In the early fourteenth century the metropolitan archbishop made Moscow the ecclesiastical capital of Russia.

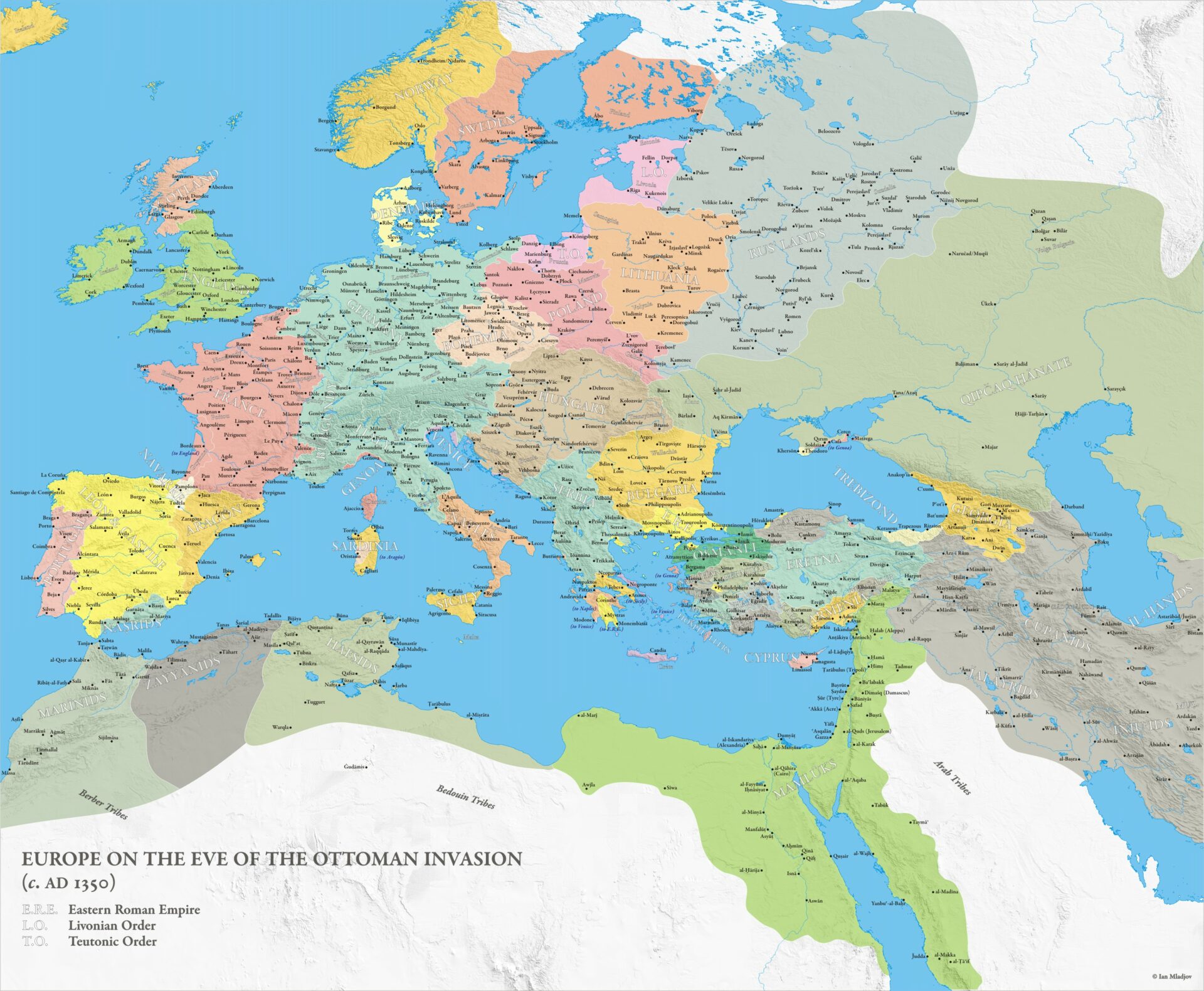

By the middle of the fifteenth century, Moscow was a self-conscious Russian national state that could undertake successful wars against both the Polish-Lithuanian kingdom and the Tatars. Ivan III (r. 1462— 1505) put himself forward as the heir to the princes of Kiev and declared that he intended to regain the ancient Russian lands that had been lost to Poles and Tatars. Many nobles living in the western lands came over to him with their estates and renounced their loyalties to the Lithuanian- Polish state. In 1492 the prince of Lithuania was forced to recognize Ivan III as sovereign of “all the Russians.”

In 1472 Ivan had married Zoe, niece of the last Byzantine emperor, Constantine XI, who had been killed fighting against the Turks in Constantinople in 1453. Ivan adopted the Byzantine title of Autocrat and began to behave like a Byzantine emperor. He sometimes used the title Czar (Caesar) and no longer consulted his nobles. Italian architects built him an enormous palace, the Kremlin (or fortress). When the Holy Roman emperor in the 1480s decided to make an alliance with Ivan III and to arrange for a dynastic marriage, Ivan responded that he already had unlimited power derived directly from God.

When a rebellious noble fled Russia under the reign of Czar Ivan IV, the Terrible (1533-1584), he wrote the czar from abroad, denouncing him for failing to consult his nobles on important questions. Ivan replied that he was free to bestow favors on his slaves or inflict punishment on them as he chose. The first to formally take the title of czar, Ivan broke the power of the Tatars, conquered Kazan, Astrakhan, and Siberia, and systematically and brutally suppressed the most powerful nobles to establish a thoroughly autocratic government.

Part of the explanation for this rapid growth of autocratic theory is that Russia lived in a constant state of war or preparation for war. Perhaps more significant is that in Moscow, feudalism had not developed a united class of nobles who would fight against the rising monarchy for their privileges, as it had in the West. Instead of uniting against the pretensions of the monarch, the Muscovite nobility produced various factions with which the monarch could deal individually.

But most important of all was the ideology supplied by the church. In the West, the church itself was a part of feudal society and jealous of its prerogatives. In Russia it became the ally of the monarchy and something like a department of state. Russian churchmen were entirely familiar with Rome’s claim to world empire and to

Constantinople’s centuries-long position as “new Rome.” With the fall of Constantinople to the Turks, they elaborated a theory that Moscow was the successor to the two former world capitals.

Russian churchmen spread the story that Rurik, the first political organizer of Russia, was descended from the brother of Augustus. They claimed that the Russian czars had inherited certain insignia and regalia not only from the Byzantines but even from the Babylonians. All the czars down to the last, Nicholas II (r. 1894-1917), were crowned with a cap and clothed with a jacket that were of Byzantine manufacture. Thus the church supplied the state with justification for its acts. Imperial absolutism became one of the chief political features of modern Russia.