A World Turned Upside Down | The Rise of the Nation

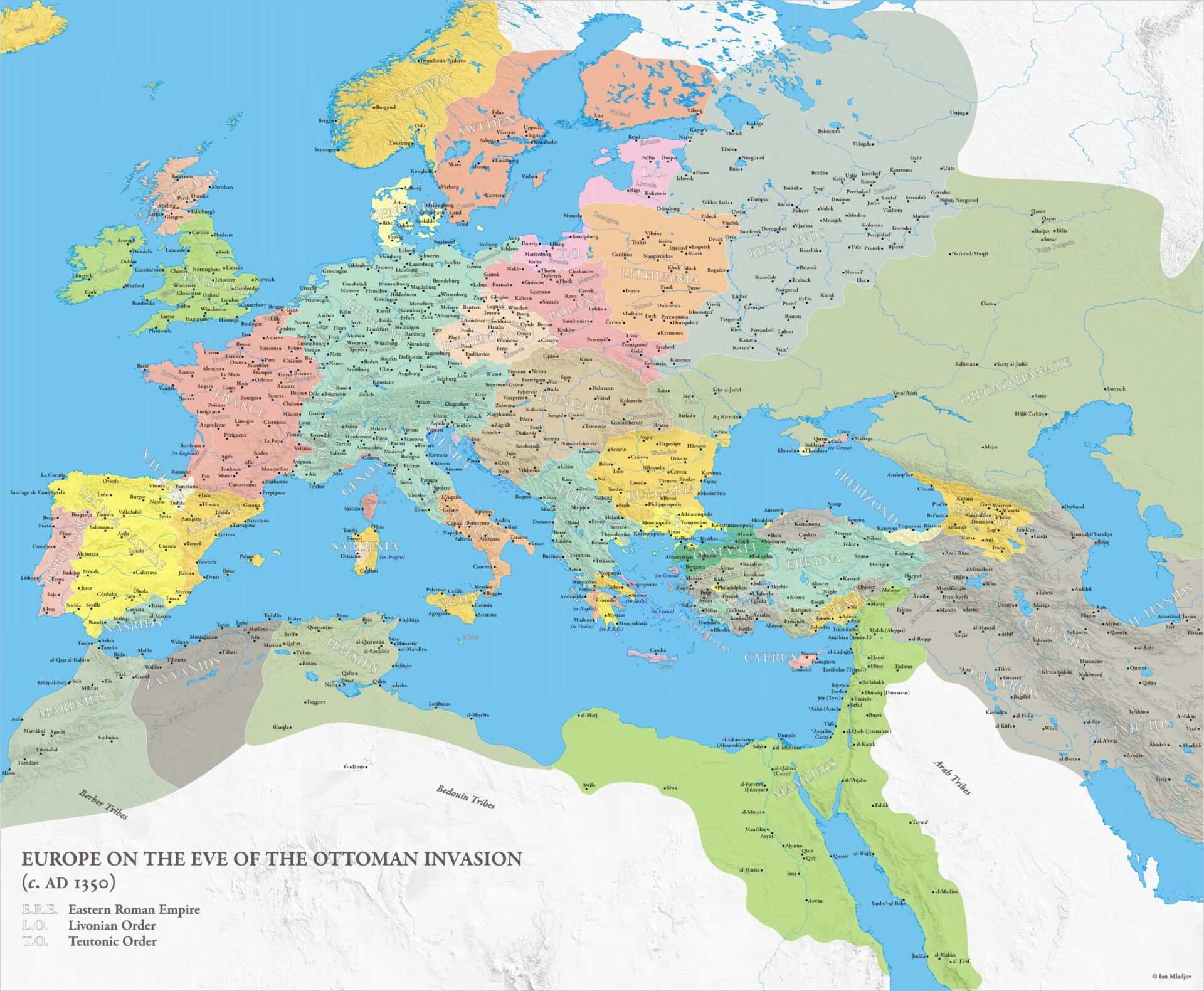

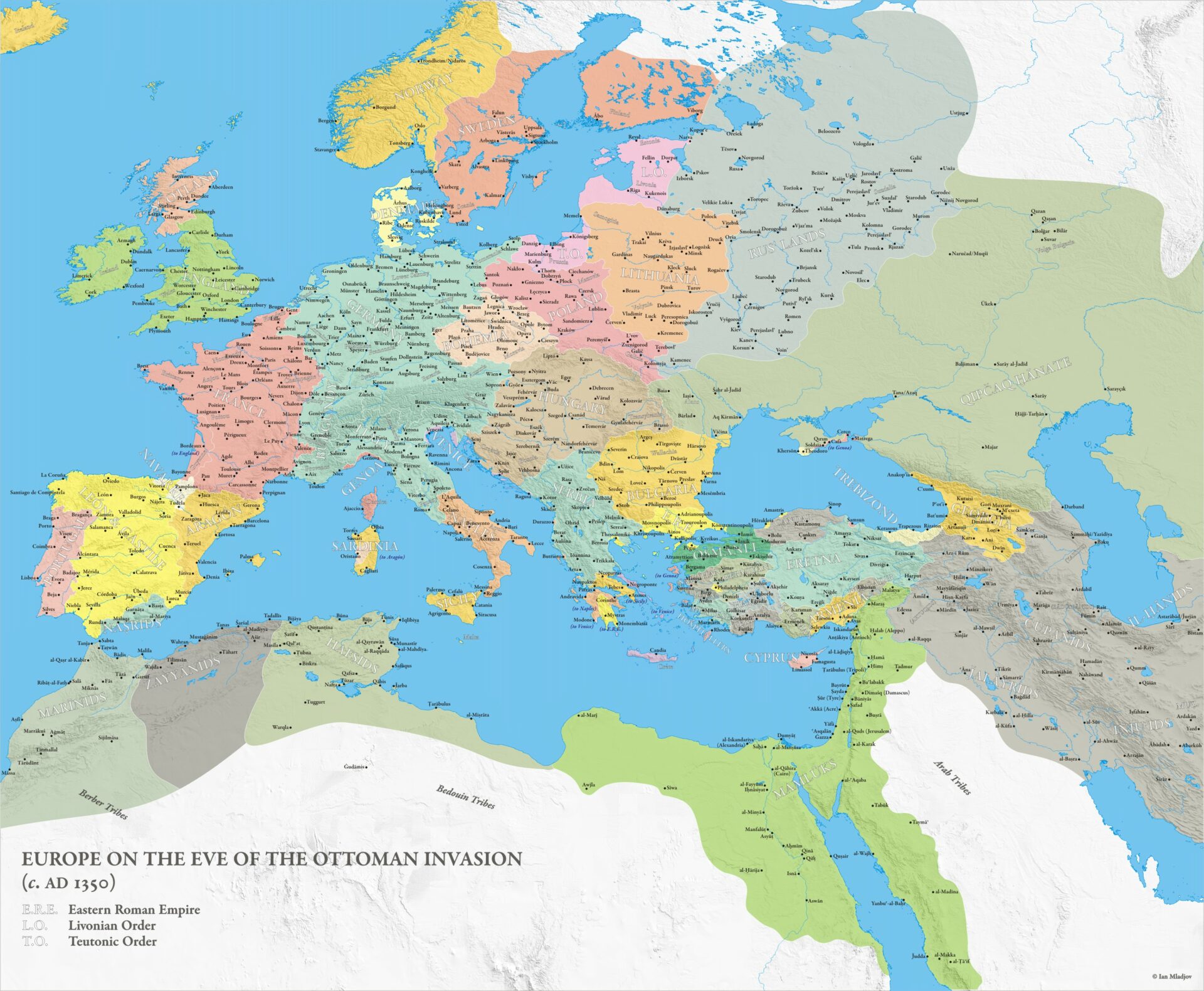

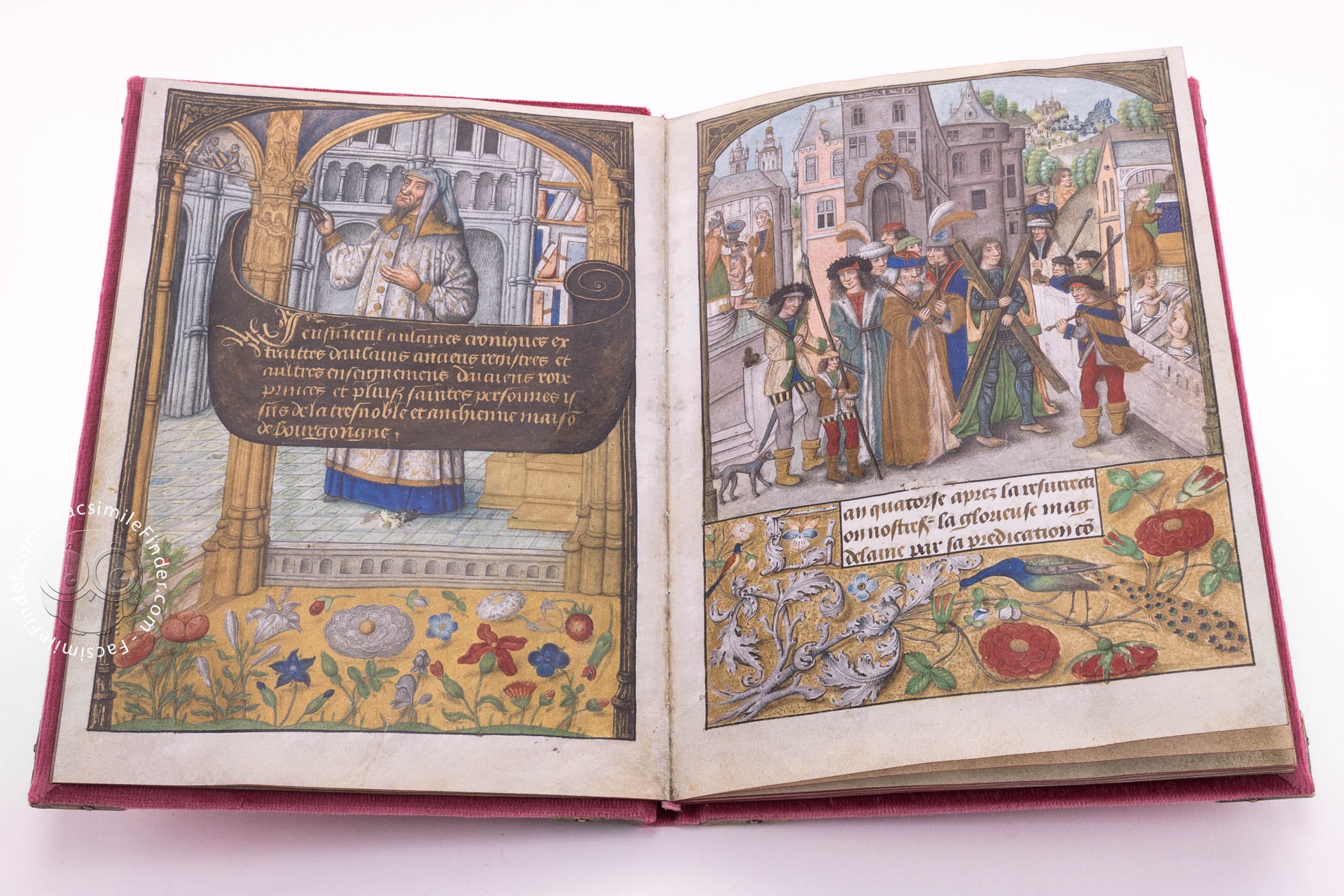

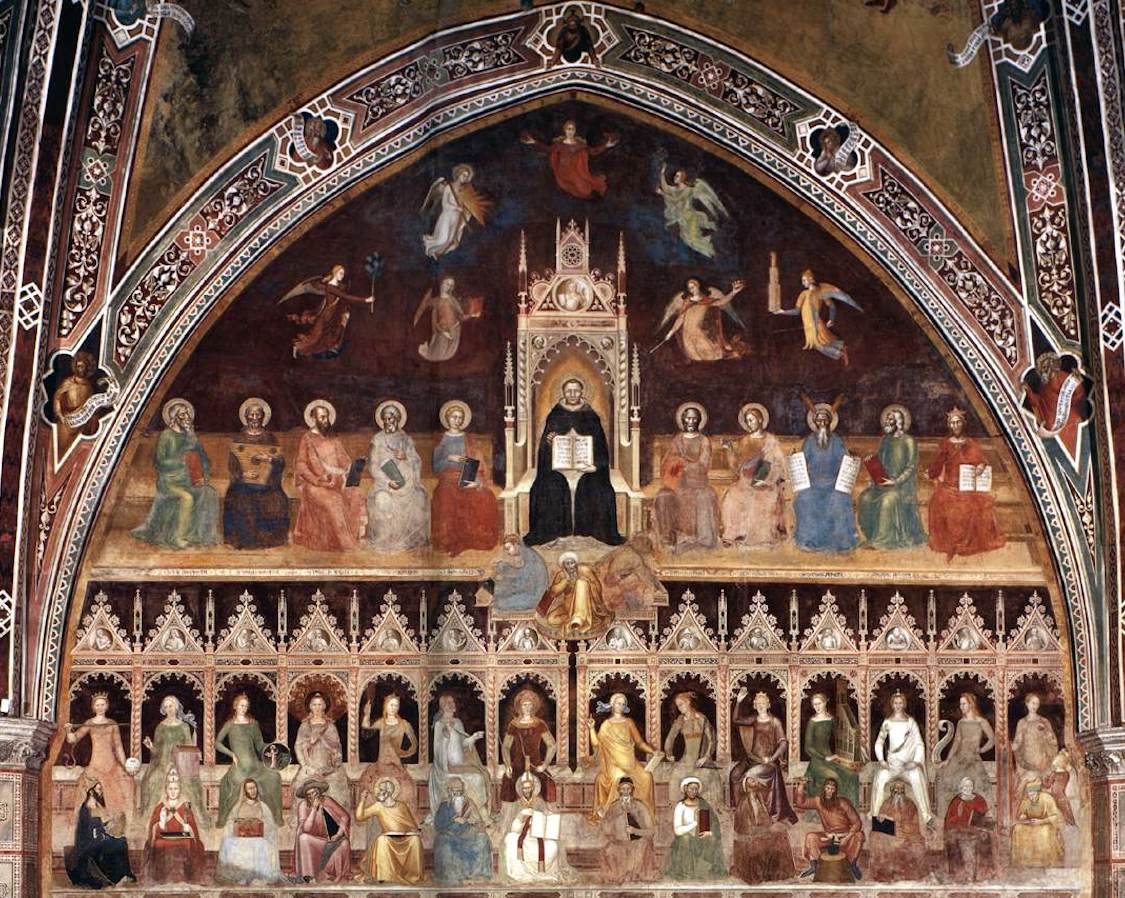

During the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries old forms and attitudes persisted in Western politics but became less flexible and less creative. The Holy Roman emperor Henry VII in the early 1300s sought to straighten out the affairs of Italy in the old Ghibelline tradition, even though he had few of the resources that had been at the command of Frederick Barbarossa. The nobles of France and England, exploiting the confusion of the Hundred Years’ War, built private armies and great castles and attempted to transfer power back from the monarch to themselves.