The Rise of Mussolini | Between The World Wars

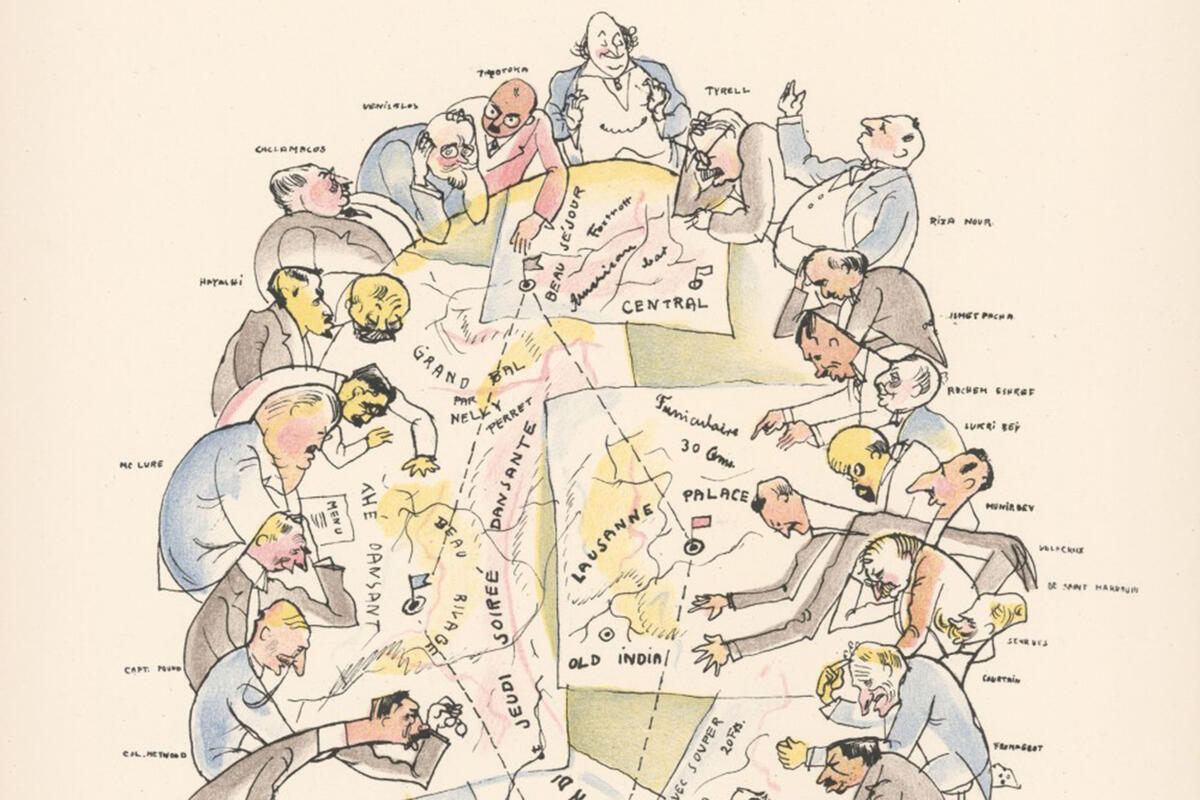

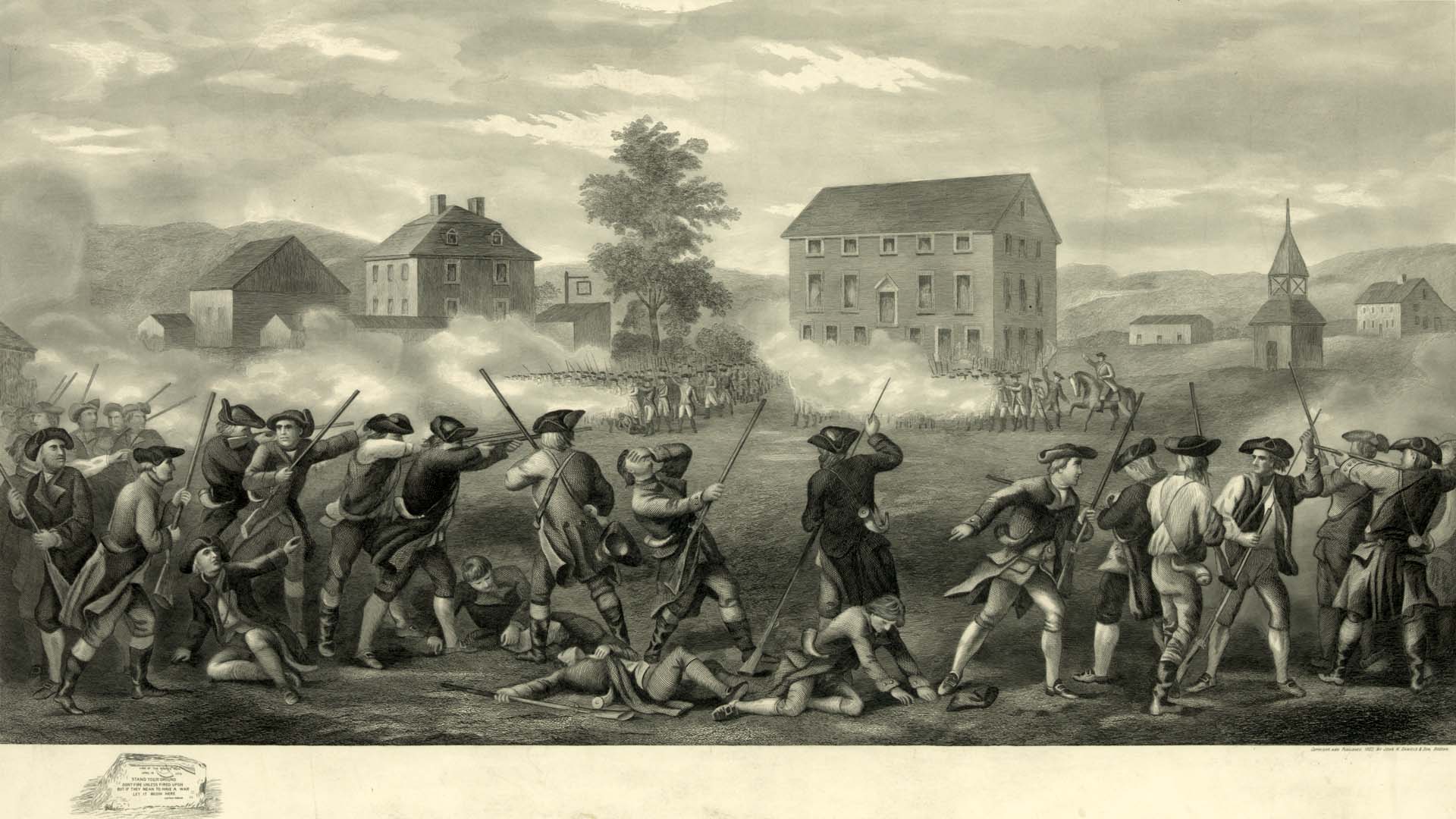

Some Italians, supporting Gabriele d’Annunzio (18631938), seized the city of Fiume, which had not been awarded to Italy by the Treaty of London. D’Annunzio ran his own government in Fiume until the end of 1920.

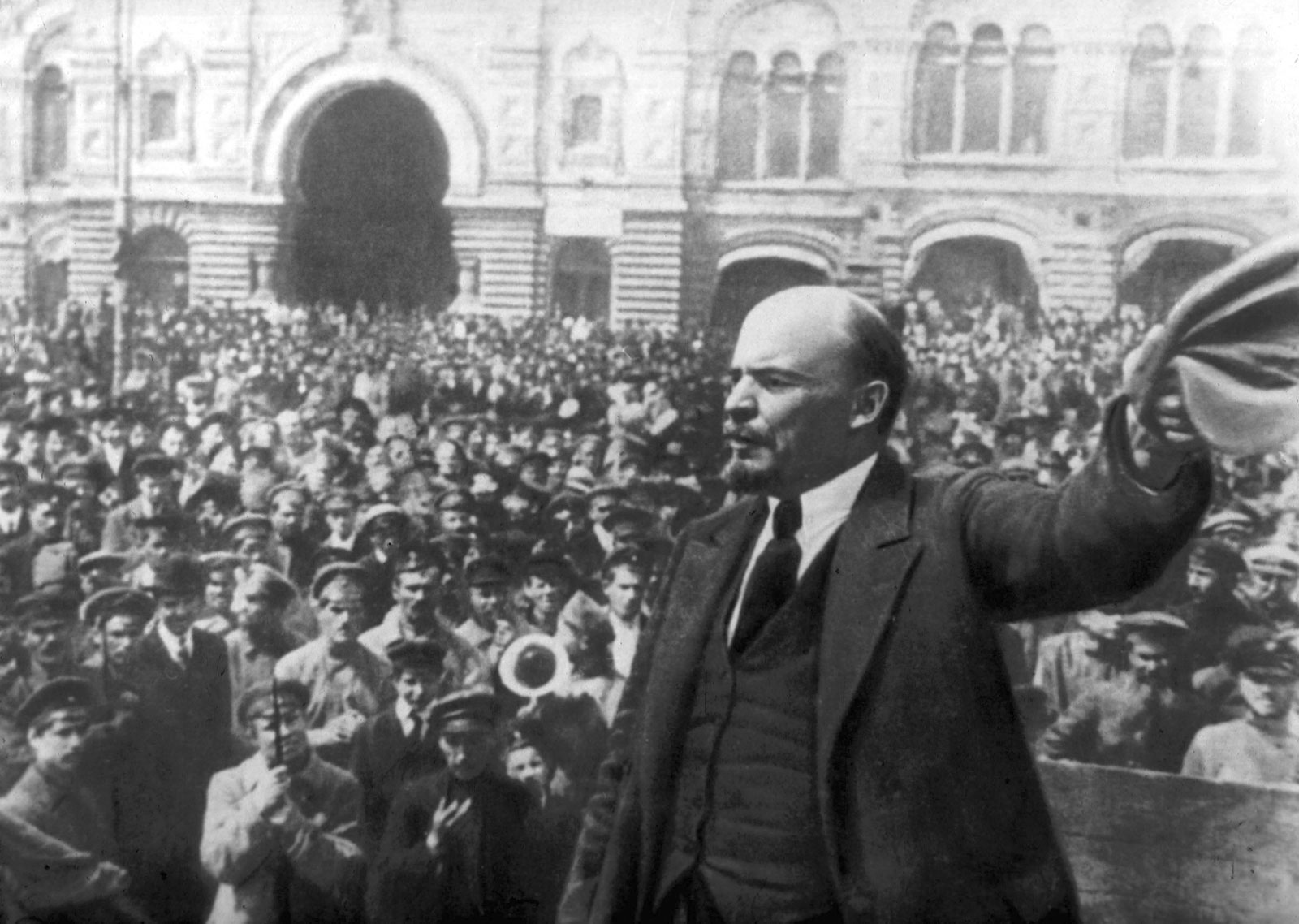

In November 1920, when the Italian government signed the Treaty of Rapallo with Yugoslavia by which Fiume was to become a free city, Italian forces drove d’Annunzio out. But d’Annunzio’s techniques of force, haranguing of mobs from a balcony, straight-arm salute, black shirts, rhythmic cries, and plans for conquest inspired Benito Mussolini (1883-1945), founder of Italian fascism.