The peace conference first met formally on January 18, 1919. Nearly thirty nations involved in the war against the Central Powers sent delegates. Russia was not represented. The defeated nations took no part in the deliberations; the Germans, in particular, were given little chance to comment on or criticize the terms offered them. German anger over this failure of the Allies to accept their new republic was to play a large part in the ultimate rise of Adolf Hitler.

The conference got off to a good start. Wilson’s Fourteen Points already seemed to guarantee peace; it was believed that the proposed association of nations, working together in the freedom of parliamentary discussion, would eliminate the costly burdens of armament.

However, the conference took on a familiar pattern. The small nations were excluded from the real negotiations; the business of the conference was carried on in private among the political chiefs of the victorious great powers—the Big Four of Wilson, Lloyd George, Clemenceau, and Italian premier Vittorio Orlando (1860-1952). Decisions were made with only indirect consultation of public opinion and with all the pressures, intrigue, compromises, and bargaining common to earlier peace conferences.

The professional diplomats of the smaller states had probably never expected that they would be treated on equal terms, but the completeness of their exclusion from the work of the conference annoyed them and angered their peoples. More important, all the major powers had large staffs of experts—economists, political scientists, historians, specialists in many fields—who were confident that they would do the real work and make the real decisions. They drew up report after report, but they did not make policy. The most celebrated of these experts was an economist, John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946), who represented the British Treasury at Versailles until he quit in disgust and wrote a highly critical and influential analysis, The Economic Consequences of the Peace.

Keynes would become the most famous economist of the nventieth century. His work was both theoretical and practical. In The Economic Consequences he attacked the negotiators at Versailles, and especially Wilson, so skillfully, arguing that the treaty was unworkable as well as immoral and that it would lead to economic ruin throughout Europe, that the British were persuaded in the interwar years that so harsh a punishment of Germany required rectification.

The reception of Keynes’ work drove a wedge between the British, French, and Americans. In time Keynes would produce his General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, published in 1936, which would tackle the Great Depression that he had predicted, arguing that the usual government policy—cutting spending in the face of inflation—was wrong, and that governments should spend in order to pull the economy out of depression. This argument paved the way for deficit financing with its many short-range benefits and long- range problems.

Wilson and his experts were gradually persuaded to accept harsher peace terms. The reparations bill against Germany was lengthened; Poland, Italy, and Japan made claims to lands that could not be justified on the basis of self-determination by the peoples concerned. Wilson compromised on a dozen points, but he would not let the Italians have Fiume, though Italy might have neigh- boring Trieste and the coveted Trentino. Yet Fiume was Italian-speaking and historically was linked with Venice. The Italian delegation left the conference in anger, but Wilson was immovable.

The covenant of the League of Nations was an inte- gral part of the Treaty of Versailles. The League was no supranational body but a kind of permanent consultative system initially composed of the victors and a few neutrals. The way was left open for the Germans and the Russians to join the League, as they later did. The League had an assembly in which each member state had one vote, and a council in which five great powers (Britain, France, Italy, the United States, and Japan) had permanent seats, and to which four other member states were chosen by the assembly for specific terms.

A permanent secretariat, to be located at Geneva, was charged with administering the affairs of the League. The League never fulfilled the hopes it had aroused. It did not achieve disarmament, nor did its peacemaking machinery prevent aggression. The great powers simply went their usual ways, using the League only as their policy makers saw fit.

More relevant to the work in Paris was the problem of territorial changes. The peacemakers were confronted not merely with the claims of the victorious Allies but also with those of the new nations that had sprung up from the disintegrating Austrian, Russian, and Turkish empires. They had to try to satisfy diverse land hungers without too obviously violating the principle of “self-determination of peoples.” This principle was hard to apply in much of central Europe, where peoples of different language and national consciousness were mixed together in a mosaic of minorities. The result was to multiply the number of sovereign nations.

France regained Alsace-Lorraine. The Saar Basin was to be separated from Germany for fifteen years as an international ward supervised by the League of Nations. During that period its coal output would go to France, and at its close a plebiscite would determine its political future. The Rhineland remained part of the German Republic, though it was to be demilitarized and occupied for a time by Allied soldiers.

Belgium was given some small towns on the German border. After a plebiscite provided for in the Treaty of Versailles, Denmark recovered the northern part of Schleswig, which the Danish Crown had lost to Prussia in 1864. Poland, erased from the map as an independent state in 1795, was restored and given lands that it had possessed before the partitions of the eighteenth century but that contained large German and other minorities.

The old Habsburg Empire was completely dismembered. Charles I (1887-1922) had come to the Habsburg throne in 1916 and had sought separate peace negotiations. But the empire broke up under him as ice breaks in a spring river: on October 15, 1918, Poland declared its independence; on October 19, Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes at Zagreb declared the sovereignty of a south-Slav government; on November 1, Charles granted Hungary independence.

When Austria-Hungary signed a separate armistice on November 3, it had virtually ceased to exist. The heart of its German-speaking area was constituted as the republic of Austria, which was forbidden to join itself to Germany, and the heart of its Magyar-speaking area became a diminished kingdom of Hungary. The Czech- inhabited lands of Bohemia and Moravia were joined with Slovakia, to which were added the Ruthenian lands of the Carpatho-Ukraine frontier further east to form the “successor state” of Czechoslovakia.

Another successor state was Yugoslavia, officially the kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, a union between prewar Serbia and the south-Slav territories of the Habsburgs. Romania, which received the former Hungarian province of Transylvania, was also rewarded with Bessarabia, a Russian province that the Bolsheviks could not defend. Greece received Thrace at the expense of Turkey and Bulgaria. Wilson’s refusal to accept the partition of Albania among Yugoslavia, Italy, and Greece saved that country from destruction.

Out of the former czarist domains (other than Poland) held at the end of the war by the Germans, the Baltic republics of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania were created. In time plebiscites determined other territorial adjustments, notably whether parts of East Prussia and Silesia should go to Poland or remain German. The new Polish state was granted access to the Baltic Sea through the so-called Polish Corridor, a narrow strip of land that had once been Polish and that terminated in the almost wholly German port of Danzig. The Poles wanted Danzig, but the Allies compromised by making it a free city and by giving the Poles free trade with it. The Polish Corridor now separated East Prussia from the rest of Germany, and Germans had to cross it in sealed trains.

Outside Europe the Near East presented the most acute problems. By the Treaty of Sevres of October 1920, the Turks were left with only Constantinople and a small area around it in Europe, and with Anatolia in Asia. Mesopotamia (contemporary Iraq) and Palestine were given as mandates to Britain, while Syria and Lebanon were granted as mandates to France. The Greeks were to hold Smyrna and nearby regions in Asia Minor for five years, after which the mixed Greek and Turkish population would be entitled to a plebiscite.

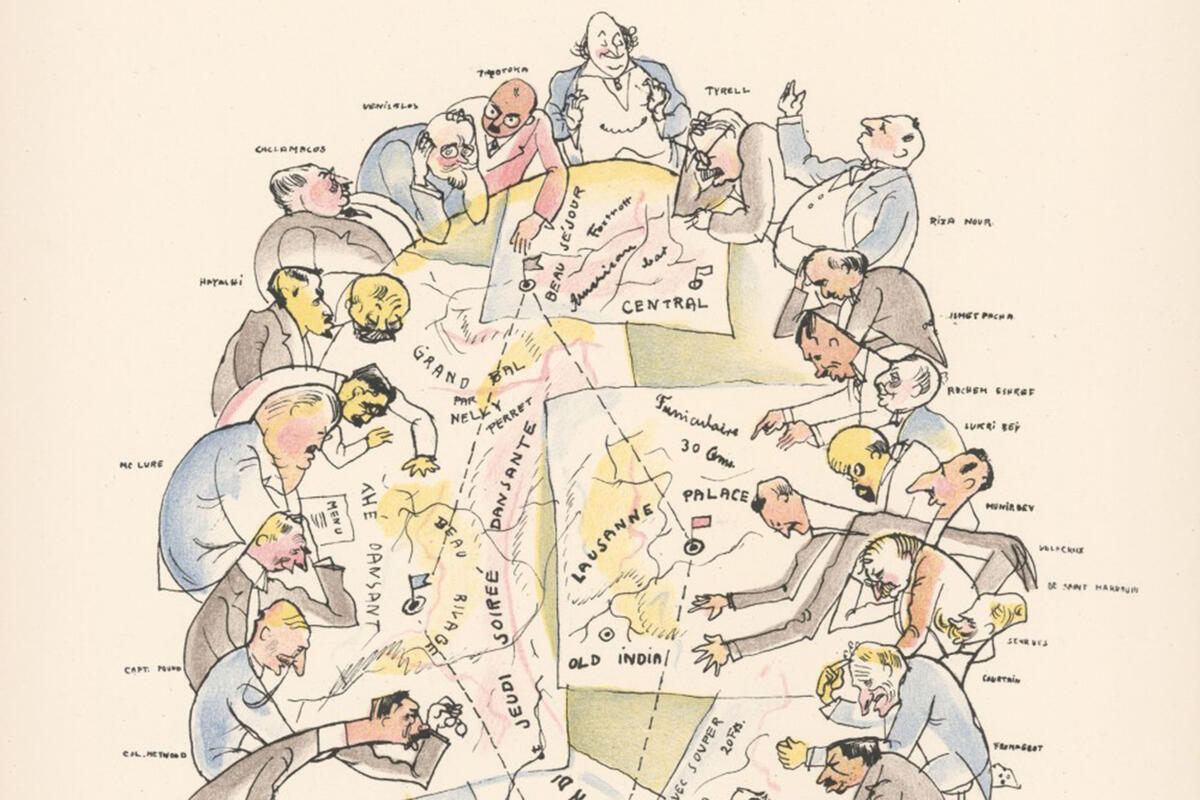

But the Treaty of Sevres never went into effect, though it was signed by the sultan. A group of army officers headed by Mustafa Kemal led a popular revolt in Anatolia against the government at Constantinople and galvanized the Turkish people into a renewed nationalism. In the Greco-Turkish War of 1921-1922, the Turks drove the Greek army into the sea and set up a republic with its capital at Ankara in the heart of Anatolia. The Allies were obliged to conclude the Treaty of Lausanne with this new government in 1923; the new treaty transferred the area of Izmir (Turkish for Smyrna) and eastern Thrace from Greek to Turkish control and was much more advantageous to the Turks than the Treaty of Sevres had been.

The Lausanne settlement included a radical innovation: a formal transfer of populations, affecting 2 million people. Greeks in Turkey, except for Istanbul, were moved to Greece, and Turks in Greece, except for western Thrace, were moved to Turkey. Each government was to take care of the transferred populations, and though much hardship resulted, on the whole the plan worked. No such exchange occurred on Cyprus, the British-controlled island in the eastern Mediterranean, where Greeks outnumbered Turks four to one and where the two peoples were so thoroughly intermingled in the towns and villages that an exchange would have been extremely difficult. Nor were measures taken to satisfy the national aspirations of two other minorities—the Muslim Kurds of eastern Anatolia and the Christian Armenians, many now dispersed from northeastern Anatolia to northern Syria.

Under the mandate system, control over a con- quered territory was assigned to a power by the League of Nations, which undertook to see that the terms of the mandate were fulfilled. This system was designed to prepare colonial peoples for eventual independence. Under it the former German overseas territories and the non- Turkish parts of the Ottoman Empire were distributed. Of Germany’s African possessions, East Africa went to Britain; Southwest Africa went to the Union of South Africa; and both the Cameroons and Togoland were divided between Britain and France. In the Pacific the German portion of New Guinea went to Australia, western Samoa to New Zealand, and the Caroline, Marshall, and Mariana island groups to Japan. In the Near East France secured Syria and Lebanon, while Britain took Palestine, Transjordan, and Iraq (the new Arabic desig- nation for Mesopotamia).

After land transfers, the most important business of the peace conferences was reparations, which were imposed on Austria, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Turkey, as well as on Germany. It was, however, the German reparations that so long disturbed the peace and the economy of the world. The Germans had to promise to pay for all the damage done to civilian property during the war, and to pay at the rate of $5 billion a year until 1921, when the final bill would be presented to them. They would then be given thirty years in which to pay the full amount. The amount was left indefinite at Versailles, for the Allies could not agree on a figure, but the totals suggested were astronomical.

The Versailles settlement also required Germany to hand over many merchant ships to the Allies and to make large deliveries of coal to France, Italy, and Belgium for ten years. The western frontier zone, extending to a line fifty kilometers east of the Rhine, was to be completely “demilitarized”—that is, to contain neither fortifications nor soldiers. In addition, the Allies could maintain armies of occupation on the left bank of the Rhine for fifteen years or longer. The treaty forbade Germany to have either submarines or military planes and severely limited the number and size of surface vessels in its navy. Finally, Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles obliged Germany to admit that the Central Powers bore sole responsibility for starting the war in 1914.

The League of Nations was potentially a means by which a new generation of international administrators might mitigate the old rivalries. The reparations could be, and were, scaled down. The new successor states were based on a national consciousness that had been developing for at least a century. Though some might protest at the “Balkanization of Europe,” it would have been impossible to deny national independence to the Czechs, the Poles, the Baltic peoples, and the south Slays. Germany, though not treated generously, was not wiped off the map, as Poland had been in the eighteenth century. Versailles was simply a compromise peace.

It contained, however, too many compromises for the American people, who were not used to striking international bargains. The American refusal to ratify the Treaty of Versailles was the result of many forces. Domestic politics were an important part, for the Republicans had won control of Congress in the elections of November 1918. President Wilson, a Democrat, made no concessions to the Republicans, either by taking Republicans to Paris with him or by accepting modifications in the treaty that would have satisfied some of his Republican opponents.

The Senate feared that the League would drag the United States into future wars. Wilson declared that Article X of the League Covenant had turned the Monroe Doctrine into a world doctrine, for it guaranteed “the territorial integrity and political independence” of all League members. But opponents argued that were the United States to sign the Covenant, the League could interfere with American tariffs and immigration laws. The Senate refused to ratify the treaty and ended the technical state of war with Germany by congressional resolution on July 2, 1921. Separate treaties were then signed with Germany, Austria, and Hungary, by which the United States gained all the rights stipulated for it by the Treaty of Versailles.

It is unlikely that even a more pliable and diplomatic president than Wilson could have won Senate ratification of a defensive alliance among France, Britain, and the United States. Without United States participation, Britain refused a mere dual alliance with France against a German attack. France, still seeking to bolster its security, thereupon patched up a series of alliances with the new nations to the east and south of Germany— Poland, and the Little Entente of Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, and Romania—a wholly unsatisfactory substitute for Britain and the United States as allies.

The peace left France with uneasy dominance of Europe, dependent on the continued disarmament and economic weakening of Germany, on the continued isolation of Russia, and on the uncertain support of unstable new allies. Moreover, France had been disastrously weakened by the human and material losses of the war. Germany was in fact still the strongest nation on the Continent. The Great War had checked, but not halted, its potential ability to dominate the Continent.

One most important matter was not directly touched upon by the Versailles settlement: Russia, or the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), the formal name of the new communist state. Yet in many senses, the most important result of World War I was the emergence of this new state.