The most important of the returning Bolshevik exiles was Lenin. His real name was Vladimir Ilyich Ulianov (1870-1924), but in his writings he used the pen name Lenin, to which he sometimes prefixed the initial N, a Russian abbreviation for “nobody,” to tell his readers that he was using a pseudonym.

Son of a provincial official, Lenin became a revolutionary in the 1880s, and in the early years of the SDs he led the party’s Bolshevik wing. He had returned to Russia from abroad for the Revolution of 1905, but he left Russia once more in 1908. From abroad he joined with a small group of socialists in opposing the war and urging that it be transformed into a class war. He considered the war to be the product of imperialism, itself produced by capitalism; thus, war, empires, and capitalism must all be destroyed if society was to be reformed.

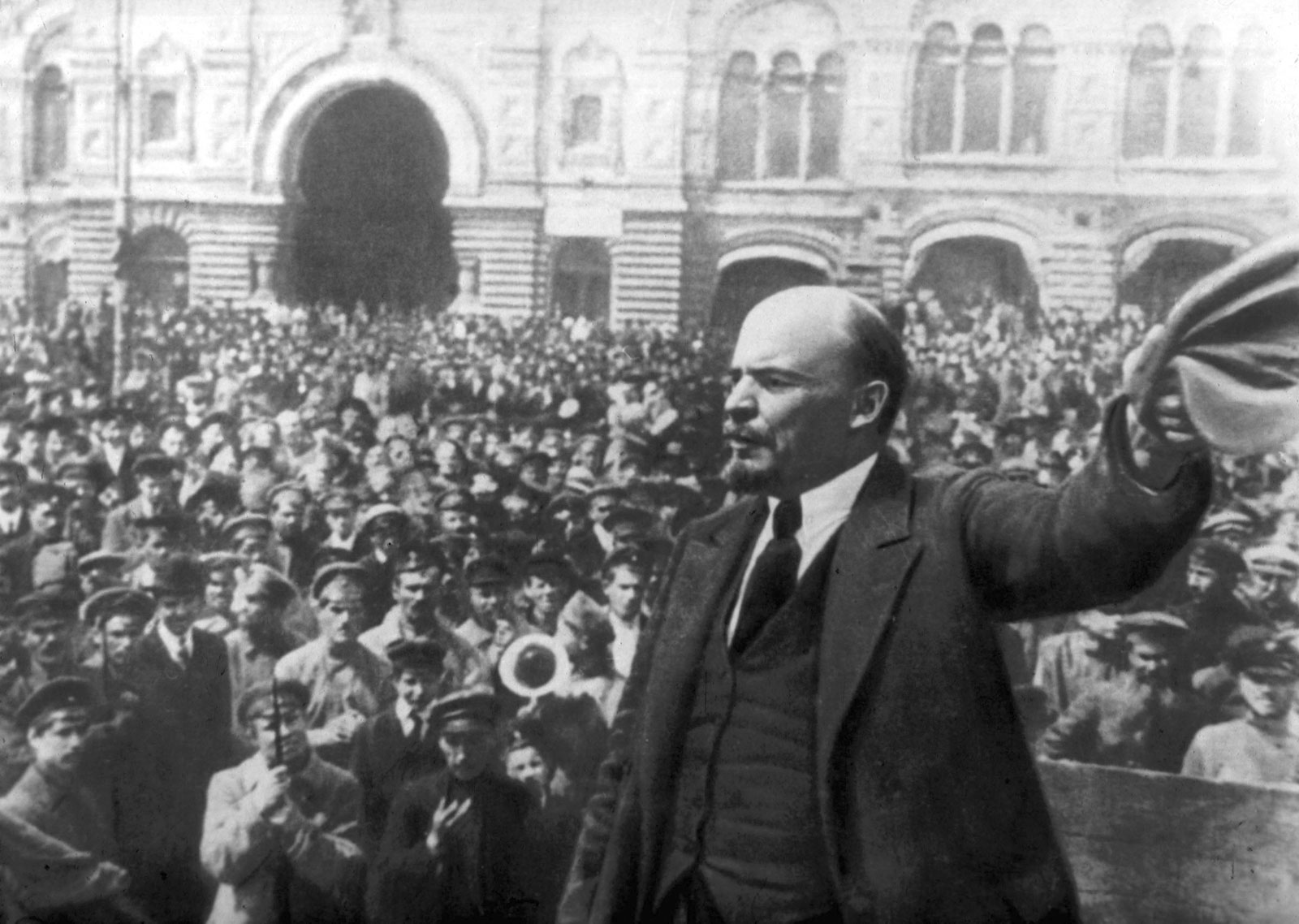

Though he had for a time despaired of living to see a true socialist revolution, Lenin was anxious to get back to Russia. The German general staff thought his return would help disrupt the Russian war effort, so the German military transported Lenin and other Bolshevik leaders across Germany from Switzerland to the Baltic in a sealed railroad car. Lenin arrived at the Finland station in Petrograd on April 16, 1917, a little more than a month after the March revolution.

Most Russian Social Democrats had long regarded a bourgeois parliamentary republic as a necessary preliminary stage to an eventual socialist revolution. There- fore, they were prepared to help transform Russia into a capitalist society. They favored the creation of a democratic republic and believed that complete political freedom was absolutely essential for their own rise to power. Despite the Marxist emphasis upon the industrial labor- ing class as the only proper vehicle for revolution, Lenin early realized that in Russia, where the “proletariat” embraced only about 1 percent of the population, the SDs must seek other allies.

During the Revolution of 1905 he had begun to preach the need for limited tactical alliances between the Bolsheviks and the SRs, who commanded the support of the peasantry; when that alliance had served its purpose, the SDs were to turn on their allies and destroy them. Then would come the socialist triumph. Lenin’s view, however, was not adopted, even by most Bolsheviks. Together with the Mensheviks, they continued to urge that a bourgeois revolution and a parliamentary democracy were necessary first steps.

Because Lenin did not trust the masses to make a revolution (by themselves, he felt, they were capable only of trade-union consciousness), he favored a dictatorship of the Bolshevik party over the working class. Because he did not trust the rank and file of Bolshevik party workers, he favored a dictatorship of a small elite over the Bolshevik party. And in the end, because he did not trust anyone’s views but his own, he favored, though never explicitly, his personal dictatorship over this elite. Another future Russian leader, the brilliant Lev Davidovich Bronstein, known as Leon Trotsky (1879-1940), early warned that Lenin’s views implied one-man dictatorship.

Trotsky, for his part, argued that the Russian bourgeoisie was so weak that the working class could telescope the bourgeois and socialist revolutions into one continuous movement. After the proletariat had helped the bourgeoisie achieve its revolution, the workers could move immediately to power, and could nationalize industry and collectivize agriculture. Although foreign intervention and civil war were to be expected, the Russian proletariat would soon be joined by the proletariats of other countries, who would make their own revolutions. Except for this last point, Trotsky’s analysis accurately forecast the course of events.

Lenin’s greatest talent was as a skillful tactician. Even before he returned to Russia in 1917, he had assessed some of the difficulties facing the provisional government and decided that the masses could take over at once. Immediately upon his arrival, therefore, he hailed the worldwide revolution, proclaiming that the end of imperialism, the last stage of capitalism, was at hand and demanding that all power immediately be given to the soviets. These doctrines were known as the April Theses.

Almost no one save Lenin felt that the loosely organized soviets could govern the country or that the war would bring down the capitalist world in chaos. Still, Lenin called not only for the abandonment of the provisional government and the establishment of a republic of soviets but for the confiscation of estates, the nationalization of land, and the abolition of the army, government officials, and the police. He was offering land at once to the impatient peasants, peace at once to the war-weary populace.

This program fitted the mood of the people far better than the cautious efforts of the provisional government to bring about reform by legal means. Dogmatic, furiously impatient of compromise, and entirely convinced that he alone had the courage to speak the truth, Lenin galvanized the Bolsheviks into a truly revolutionary group waiting only for the right moment to seize power.