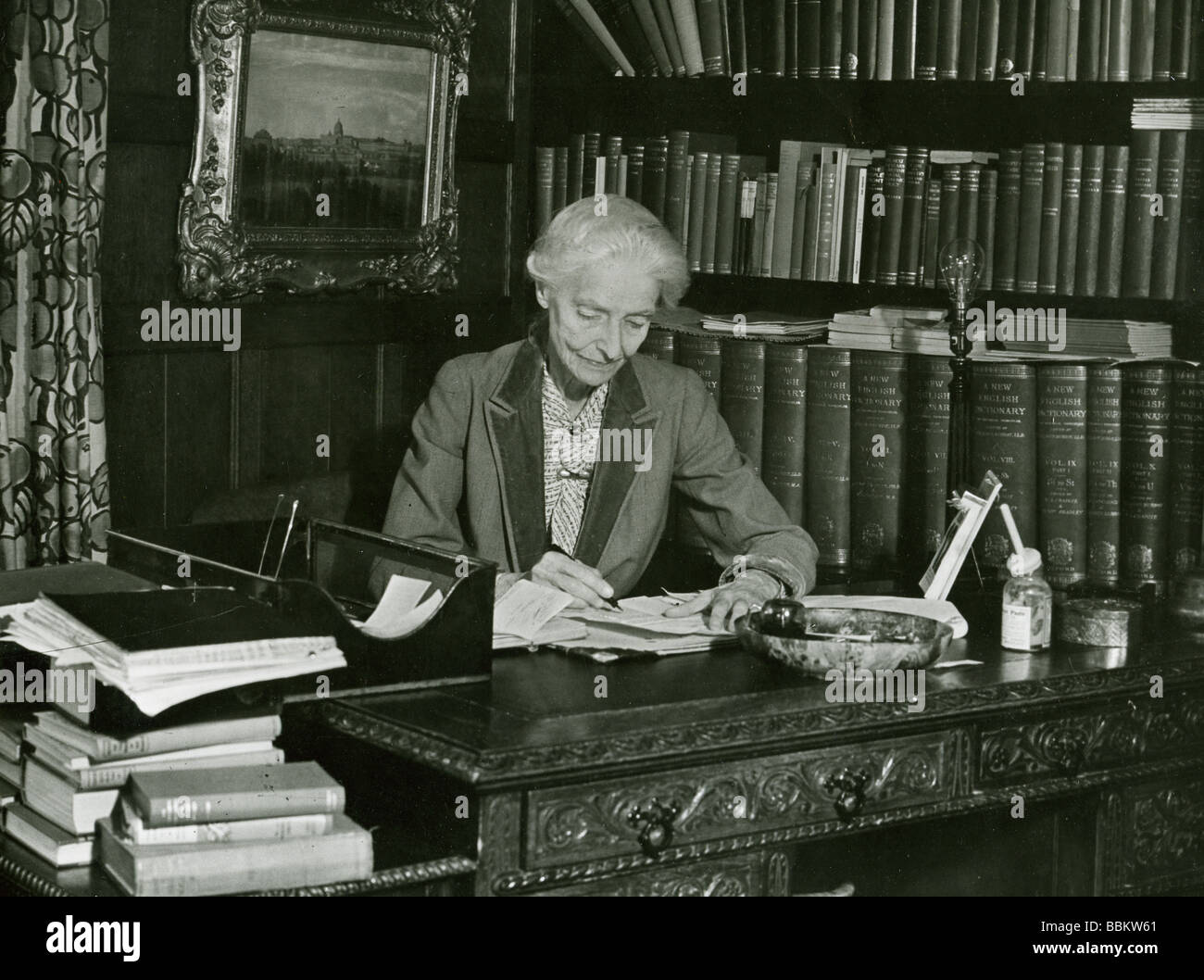

One of the leading intellectuals in the socialist movement in Britain was Beatrice Potter, who became the wife of the Fabian socialist and administrator Sidney Webb. In My Apprenticeship she addressed the question, “Why I Became a Socialist.”

Can I describe in a few sentences the successive steps in my progress towards Socialism?

My studies in [London’s] East End life had revealed the physical misery and moral debasement following in the track of the rack-renting landlord and capitalist profit- maker in the swarming populations of the great centres of nineteenth-century commerce and industry. It is true that some of these evils—for instance, the low wages, long hours and insanitary conditions of the sweated industries, and the chronic under-employment at the docks, could, I thought, be mitigated, perhaps altogether prevented by appropriate legislative enactment and Trade Union pressure.

By these methods it might be possible to secure to the manual workers, so long as they were actually at work, what might be regarded from the physiological standpoint as a sufficient livelihood. Thus, the first stage in the journey—in itself a considerable departure from early Victorian individualism—was an all-pervading control, in the interest of the community, of the economic activities of the landlord and the capitalist.

But however ubiquitous and skillful this State regulation and Trade Union intervention might become, I could see no way out of the recurrent periods of inflation and depression—meaning, for the vast majority of the nation, alternate spells of overwork and unemployment— intensified, if not actually brought about by the speculative finance, manufacture and trading that was inspired by the mad rush to secure the maximum profit for the minority who owned the instruments of production.

Moreover, “Man does not live by bread alone”; and without some “socialism”—for instance, public education and public health, public parks and public provision for the aged and infirm, open to all and paid for out of rates and taxes, with the addition of some form of “work or maintenance” for the involuntarily unemployed—even capitalist governments were reluctantly recognising, though hardly fast enough to prevent race-deterioration, and the regime of private property could not withstand revolution. This “national minimum” of civilised existence, to be legally ensured for every citizen, was the second stage in my progress toward socialism.