-

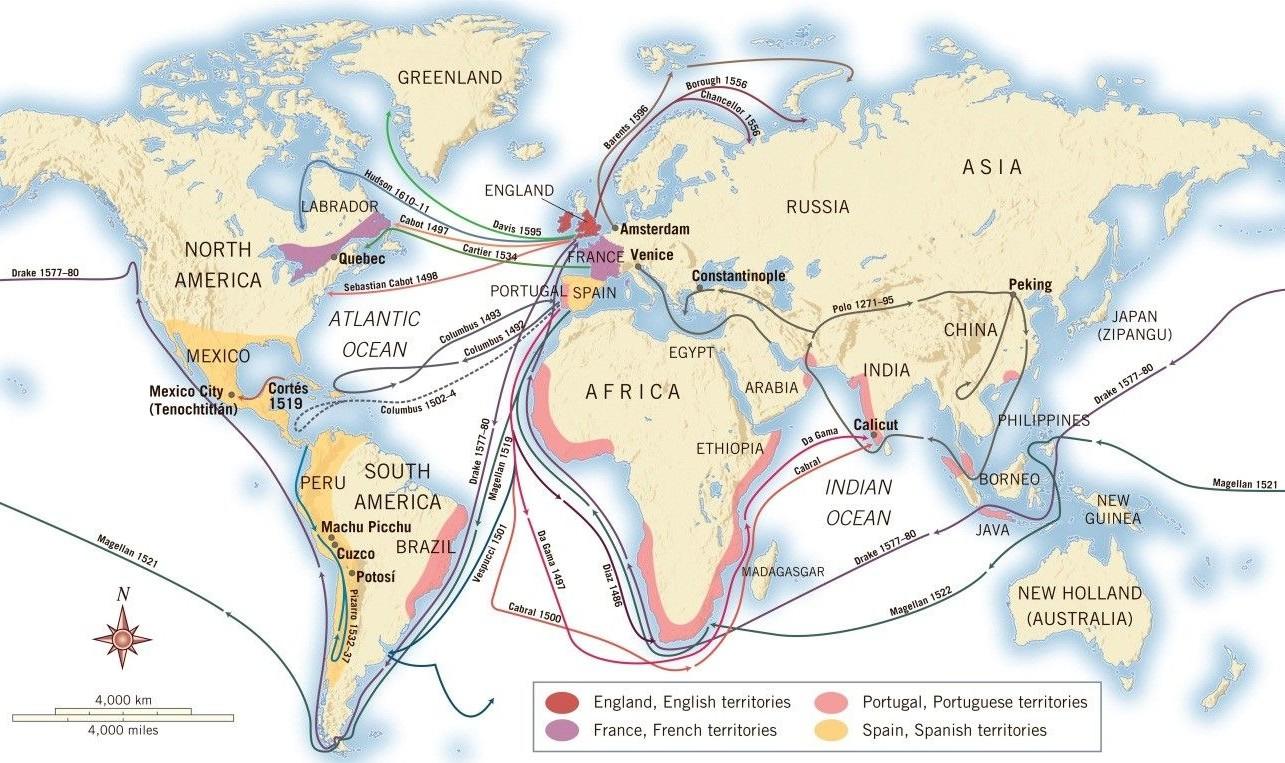

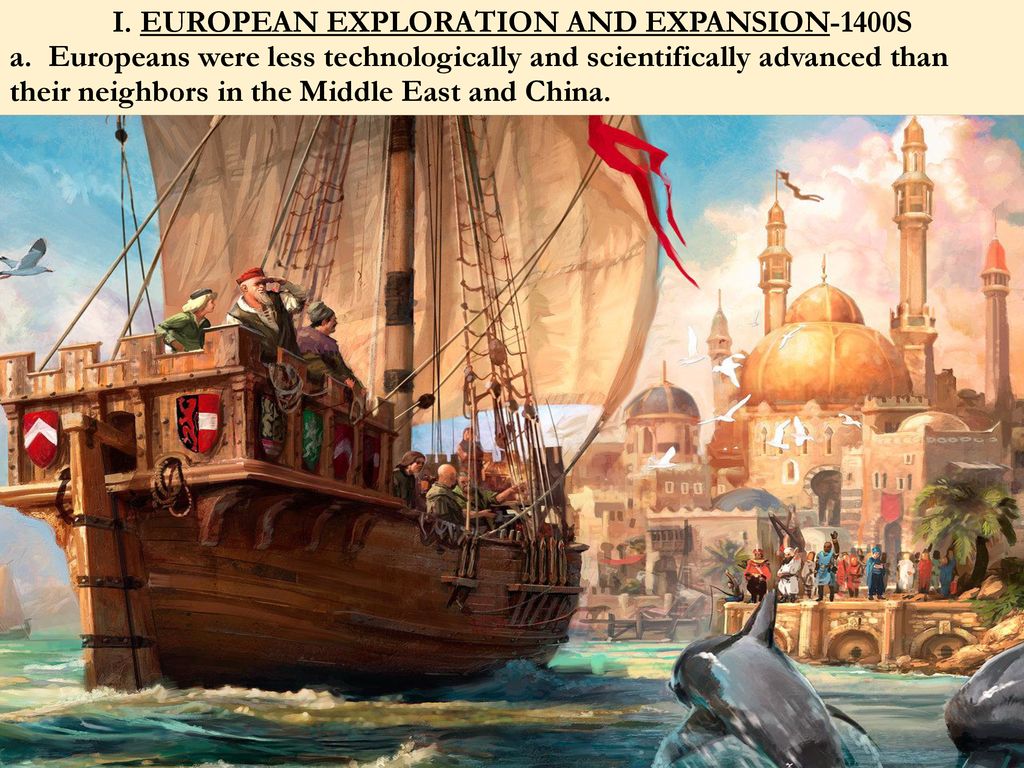

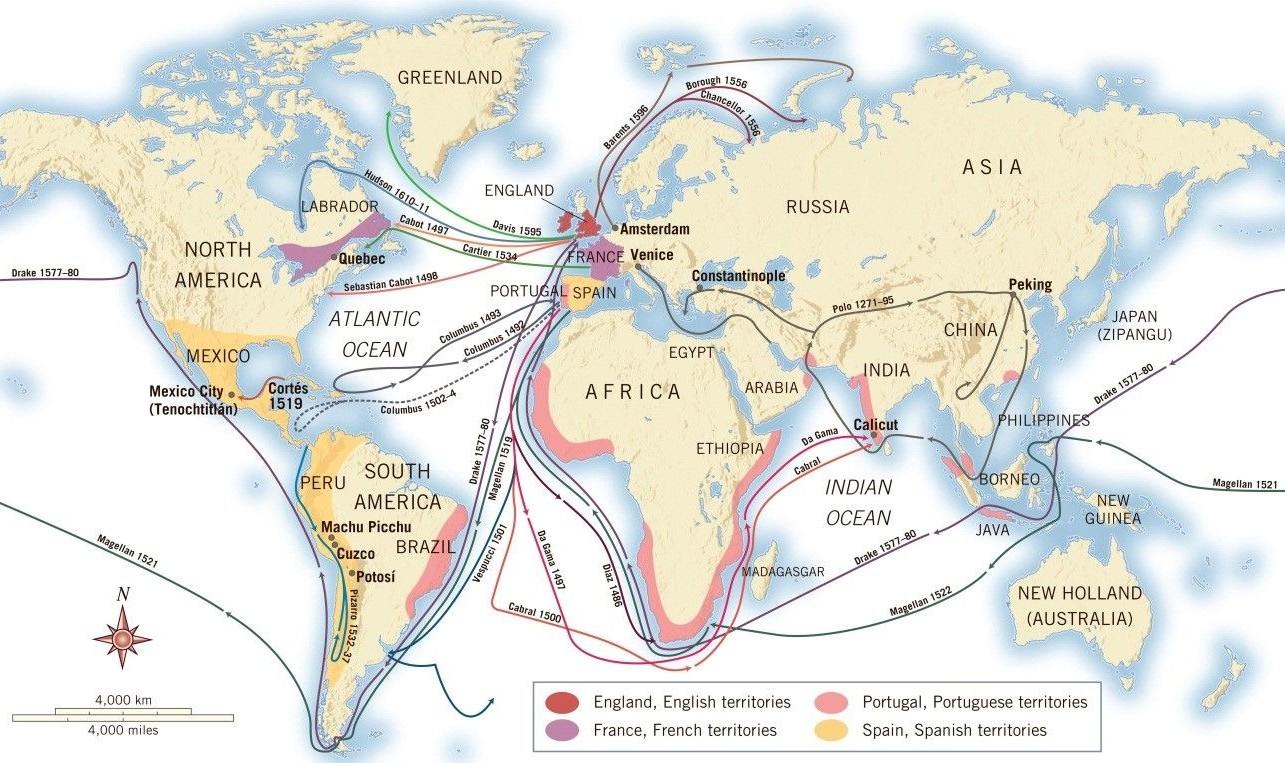

The North Atlantic Powers | European Exploration and Expansion

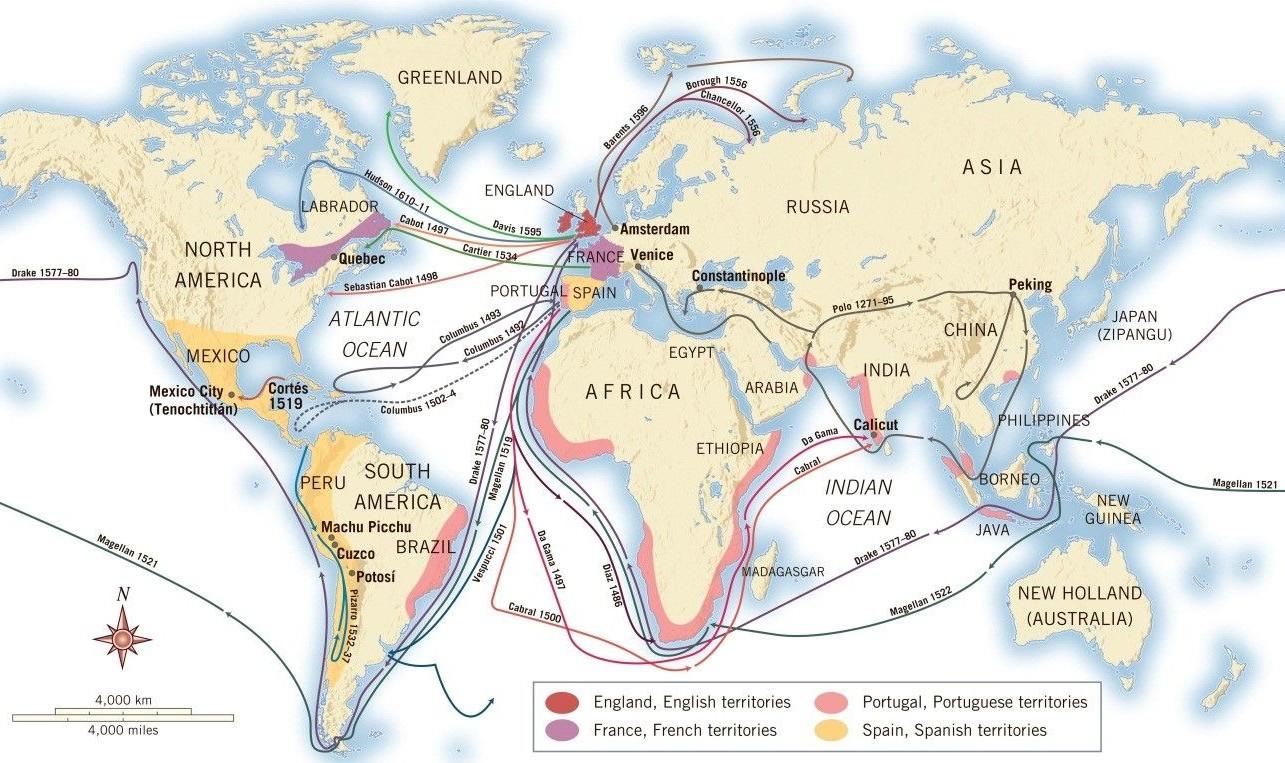

Spain and Portugal enjoyed a head start of nearly a century in founding empires of settlement. The northern Atlantic states soon made up for their late start, however. As early as 1497 John Cabot (d. c. 1498) and his son Sebastian, Italians in English service, saw something of the North American coast and gave the…

-

The Hazards of Exploration

A routine entry from the journal of Antonio Pigafetta (c. 1491–c. 1536), who completed the circumnavigation of the globe begun by Magellan, tells of daily pain and deprivation. On Wednesday the twenty-eighth of November, one thousand five hundred and twenty, we issued forth from the said strait [of Magellan] and entered the Pacific Sea, where…

-

The Growth of the Spanish Empire | European Exploration and Expansion

By the Treaty of Tordesillas Spain and Portugal had divided the world open to trade and empire along a line cut through the Atlantic, so that Brazil became Portuguese. This same line extended across the poles and cut the Pacific, so that some of the islands Magellan discovered came into the Spanish half. Spain conveniently…

-

Columbus Describes the New World

As he neared the end of his first voyage, Christopher Columbus prepared a letter for the king of Spain in which he described the islands he had discovered.

-

Columbus and Later Explorers | European Exploration and Expansion

Columbus (1451-1506), born in Genoa, was an experienced sailor and had gone at least once to the Gold Coast of Africa; he may also have sailed to Iceland. His central obsession, that the Far East (“the Indies”) could be reached by sailing westward from Spain, was not unique. No educated person in 1492 seriously doubted…

-

West by Sea to the Indies | European Exploration and Expansion

In the earliest days of concerted effort to explore the oceans, the rulers of Spain had been too busy disposing of Muslim Granada and uniting the separate parts of Spain to patronize scientific exploration as the Portuguese had done. But Spanish traders were active, and Spain was growing in prosperity.

-

The Growth and Decline of the Portuguese Empire | European Exploration and Expansion

Along the coasts of Africa, India, and China, the Portuguese established a series of trading posts over which they hoisted their flag as a sign that these bits of territory had been annexed to the Portuguese Crown. Such posts were often called factories after the factors, or commercial agents, who were stationed there to trade…

-

China | European Exploration and Expansion

China, too, resisted the West. China also saw its armed forces beaten whenever they came into formal military conflict with European or European-trained armies or fleets. It, too, was forced to make many concessions to Europeans—to grant treaty ports, and above all, extraterritoriality, that is, the right of Europeans to be tried in their own…

-

India | European Exploration and Expansion

India had been marginally in touch with Europe for several thousand years. Throughout the Middle Ages the Arabs had served as a link in trade, and in the sixteenth century a direct link was forged between the West and India, never to be loosened.

-

Prince Henry and the Portuguese | European Exploration and Expansion

Prince Henry of Portugal (1394-1460), known as “the Navigator,” was a deeply religious man who may well have been moved by a desire to convert the populations of India and the Far East. Indeed, many in the West were convinced that these distant peoples were already Christian, and for true salvation needed only to be…

-

East by Sea to the Indies | European Exploration and Expansion

Over the broad sweep of the growth of European empires, there was a strong tendency for one nation to dominate for a century or so and then decline. The fifteenth and sixteenth centuries tended to be dominated by the Iberian states, the seventeenth century by the Dutch, the eighteenth by the French, and the nineteenth…

-

European Exploration and Expansion

Westerners were not the first people to migrate over vast reaches of water. Even before the Viking voyages in the Atlantic, the Polynesians had settled remote Pacific islands. But the Polynesians and other early migrants were not societies in expansion, but groups of individuals on the move. The expansion of the West was different. From…

-

Exploration and Expansion

During the early modern centuries, when Europeans were experiencing the Renaissance and the Reformation and their long aftermath of traumatic conflict, some nations took part in a remarkable expansion that carried European sailors, merchants, missionaries, settlers, and adventurers to almost every quarter known world” meaning known to them— of the globe. What Westerners called “the…

-

Summary | The Great Powers in Conflict

By the sixteenth century, changes in political, social, family, and economic structure were underway that marked the beginning of what historians call the modern period. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the modern state system took shape as well-organized states competed for power in western Europe. With the emergence of Spain, France, and England came…

-

World-Machine, Rationalism, and Materialism | The Great Powers in Conflict

All these investigations in the various sciences tended to undermine the older Aristotelian concept of a thing’s being “perfect.” Instead of perfect circles, post-Copernican astronomy posited ellipses; instead of bodies moving of themselves, Newton pictured bodies responding to forces acting upon them.

-

The Scientific Revolution 1543-1700 | The Great Powers in Conflict

A major role in the cultivation of a new scientific attitude was taken by the English thinker and politician Francis Bacon. Though not himself a successful practitioner of science, Bacon was a tireless proponent of the need to observe and to accumulate data. In Novum Organum (1620) he wrote that scientists must think all things…

-

Science and Religion in the 16th Century | The Great Powers in Conflict

During the long sixteenth century and deep into the seventeenth, a slow transition from societies based on religious certainties to societies derived from secular concerns was taking place throughout western Europe. The pace was uneven; it differed markedly from place to place, and for most people religion remained at the root of human concern, since…

-

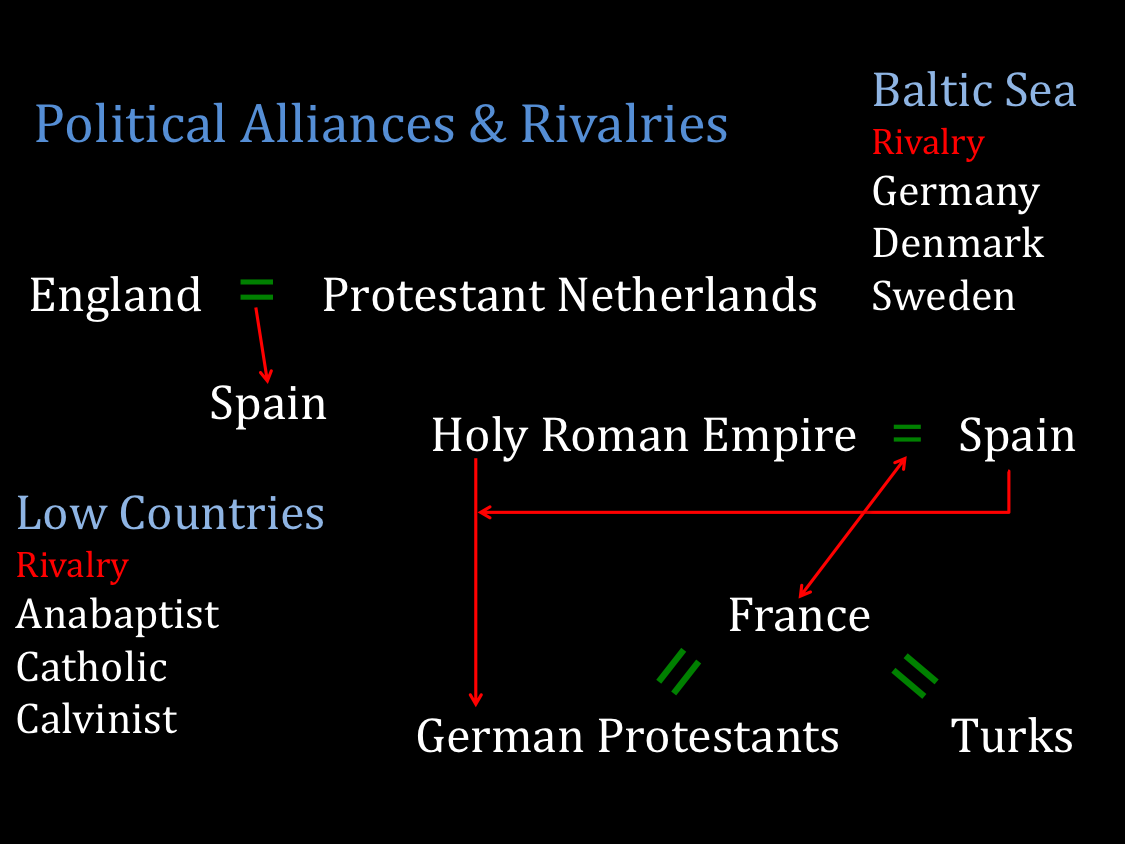

The Thirty Years’ War: The Peace of Westphalia, 1648 | The Great Powers in Conflict

The terms of the peace extended the Augsburg settlement to Calvinists as well as to Lutherans and Catholics. Princes would still “determine” the faith of their subjects, but the right of dissidents to emigrate was recognized. In most of Protestant Germany, multiplicity of sects was in fact accepted.

-

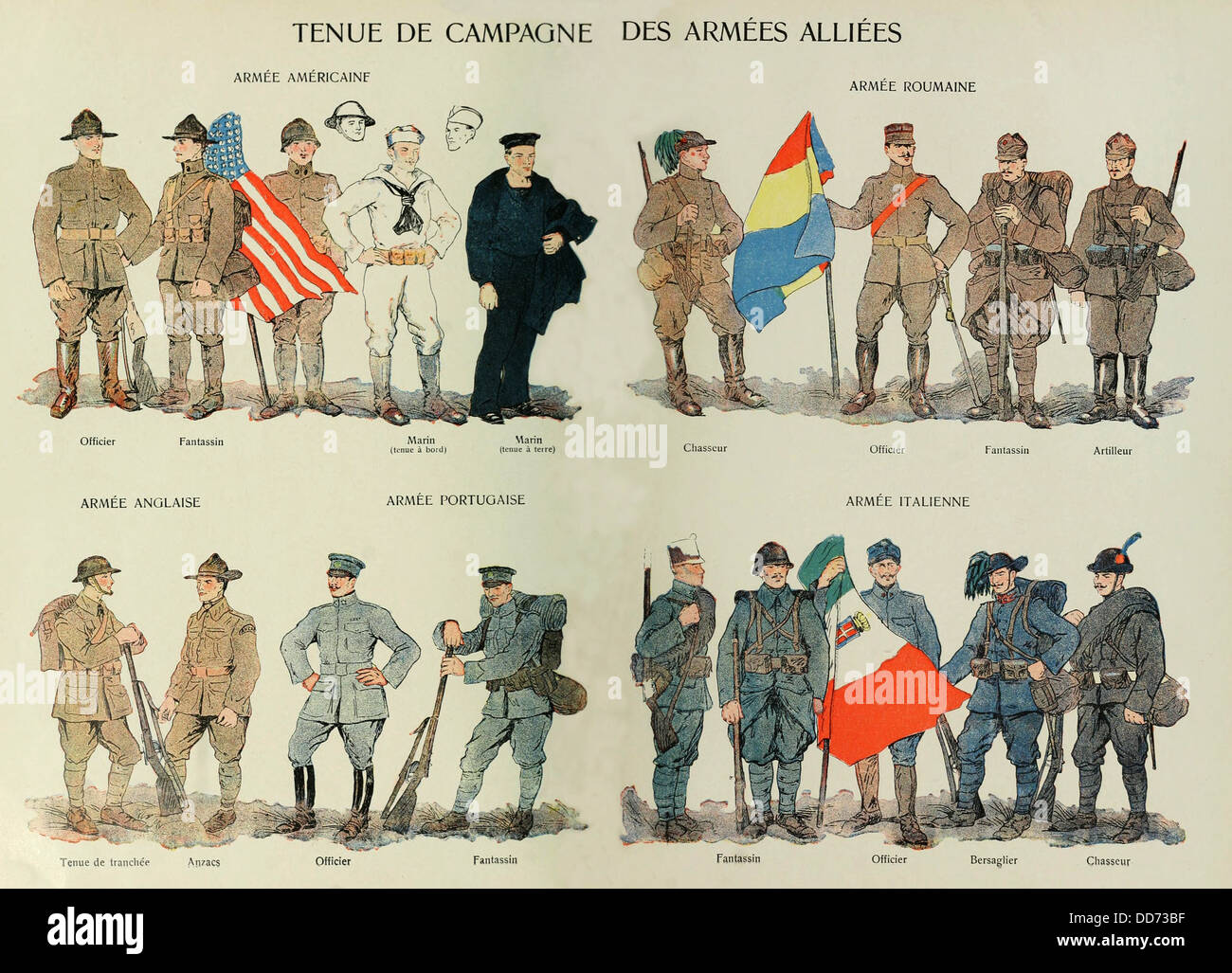

The Thirty Years’ War: The Habsburg-Bourbon Conflict, 1635-1648 | The Great Powers in Conflict

The remainder of the Thirty Years’ War was a Habsburg- Bourbon conflict. The Protestant commander had to promise future toleration for Catholicism in Germany and to undertake to fight on indefinitely in exchange for a guarantee of French men and money. The war became transformed into a struggle between emerging national identities. The armies on…

-

The Thirty Years’ War: Intervention by Denmark and Sweden, 1625-1635 | The Great Powers in Conflict

A vigorous and ambitious monarch, King Christian IV sought to extend Danish political and economic power over northern Germany. To check the Danish invasion, the German Catholics enlisted the help of the private army of Albert of Wallenstein (1583-1634). Wallenstein recruited and paid an army that lived off the land.

-

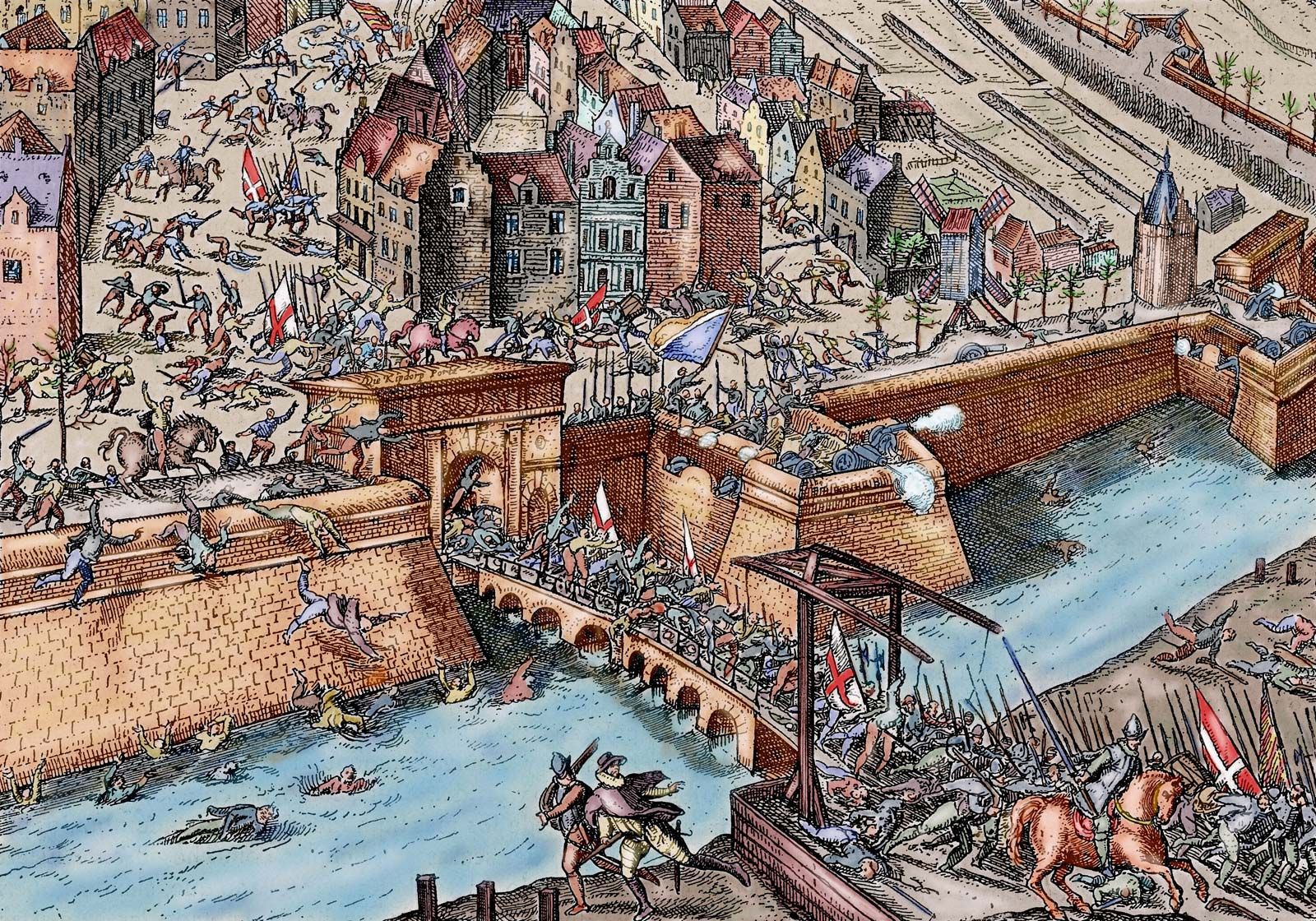

The Thirty Years’ War: The Struggle over Bohemia and the Palatinate, 1618-1625 | The Great Powers in Conflict

A major physical obstacle blocking Spanish communications was the Palatinate, a rich area in the Rhineland ruled by a Calvinist prince, the Elector Palatine. In 1618 the Elector Palatine, Frederick V, also headed the Protestant Union. Frederick hoped to break the Catholic hold on the office of emperor upon the death of the emperor Matthias…

-

Germany and the Thirty Years’ War | The Great Powers in Conflict

Like the great wars of the sixteenth century, the Thirty Years’ War of 1618-1648 was in part a conflict over religions. This time, however, most of the fighting took place in Germany. The Habsburg emperor, Ferdinand II (r. 1619-1637), made the last serious political and military effort to unify Germany under Catholic rule. The Thirty…

-

The Dutch Republic, 1602-1672 | The Great Powers in Conflict

The United Provinces of the Northern Netherlands gained independence from Spain before the death of Philip II, though formal recognition of that independence came only in 1648. The Dutch state was an aristocratic merchant society, the first significant middle-class state in Europe with virtually no landed aristocracy. Despite its small size, it was a great…

-

The English Aristocracy

Historians today emphasize that the political differences between England and the Continent reflected differences in social structure. England had its nobility or aristocracy ranging from barons to dukes. These nobles, plus Anglican bishops, composed the House of Lords. But in England, the younger sons of nobles were not themselves titled nobles, as they were on…

-

The English Renaissance: The Elizabethan Era | The Great Powers in Conflict

Elizabeth’s reign was marked by intrigue, war, rebellion, and personal and party strife. Yet there were solid foundations under the state and society that produced the wealth and victories of the Elizabethan Age and its attainments in literature, music, architecture, and science. The economy prospered in an era of unbridled individual enterprise.

-

Tudor England: Queen Elizabeth I, r. 1558-1603 | The Great Powers in Conflict

When Mary died in 1558, Henry VIII’s last surviving child was Elizabeth, daughter of Anne Boleyn. She had been declared illegitimate by Parliament in 1536 at her father’s request; Henry’s last will, however, had rehabilitated her, and she now succeeded as Elizabeth I (r. 1558-1603). She had been brought up a Protestant, and so once…

-

Tudor England: King Edward VI and Queen Mary, r. 1547-1558 | The Great Powers in Conflict

The death of Henry VIII in 1547 marked the beginning of a period of extraordinary religious shifts. Henry was succeeded by his only son, the ten-year-old Edward VI (r. 1547-1553), borne by his third wife, Jane Seymour. Led by the young king’s uncle, the duke of Somerset, as lord protector, Edward’s government pushed on into…

-

Tudor England: King Henry VIII, 1509-1547 | The Great Powers in Conflict

Critics have often accused European royalty of ruinous expenditures on palaces, retinues, pensions, mistresses, and high living in general, and yet such expenditures were usually a relatively small part of government outlays. War was really the major cause of disastrous financial difficulties for modern governments. Henry VIII’s six wives, his court, his frequent royal journeys…

-

The Edict of Nantes

By this edict Henry IV granted religious freedom to the Huguenots. Its key provisions follow: We have by this perpetual and irrevocable Edict pronounced, declared, and ordained and we pronounce, declare and ordain: I. Firstly, that the memory of everything done on both sides from the beginning of the month of March, 1585, until our…

-

The First Bourbon King: Henry IV, 1589-1610 | The Great Powers in Conflict

Henry of Navarre was now by law Henry IV (r. 15891610), the first king of the house of Bourbon. In the decisive battle of Ivry in March 1590, he defeated the Catholics, who had set up the aged cardinal of Bourbon as “King Charles X.” But Henry’s efforts to besiege Paris were repeatedly frustrated by…

-

France: Toward Absolutism, 1547-1588 | The Great Powers in Conflict

The long-established French monarchy began to move toward more efficient absolutism after the Hundred Years’ War, particularly under Louis XI. In this development, France had certain advantages. None of its provinces showed quite the intense regionalism that could be found in Catalonia or among the Spanish Basques.

-

Don Quixote

A tension runs through Cervantes’ Don Quixote. Its hero struggles against reality, and in his aspirations he is ennobled even in a world where evil often triumphs. This class work is the source of our word quixotic.

-

"The Spanish Century" | The Great Powers in Conflict

Spanish supremacy, though short-lived, was real enough. The Spanish “style” was set in this Golden Age, which has left the West magnificent paintings, architecture, and decoration, and one of the few really universal books, Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes (1547-1616). This Spanish style is not at all like those of France and Italy, even…

-

The Spanish Economy | The Great Powers in Conflict

The Iberian peninsula is mountainous, and its central tableland is subject to droughts, but its agricultural potential is considerable and it has mineral resources, notably iron. Spain was the first major European state to secure lands overseas and to develop a navy and merchant marine to integrate the vast resources of the New World with…

-

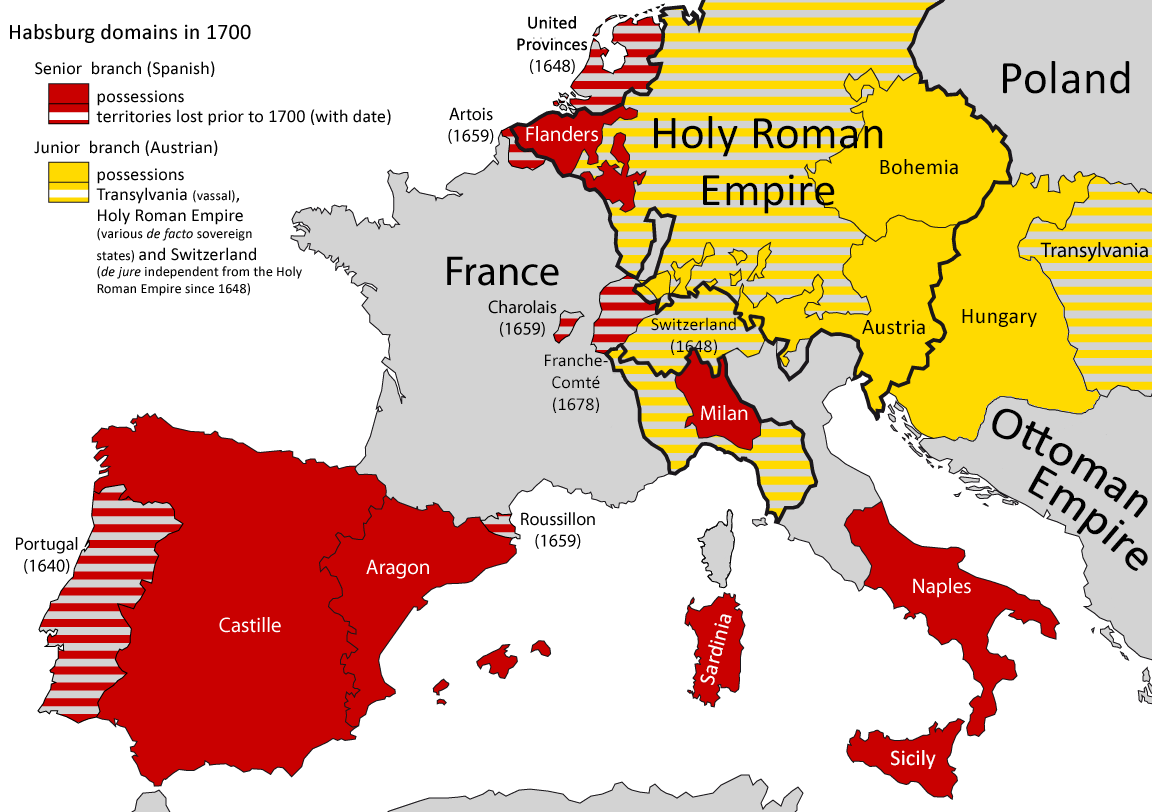

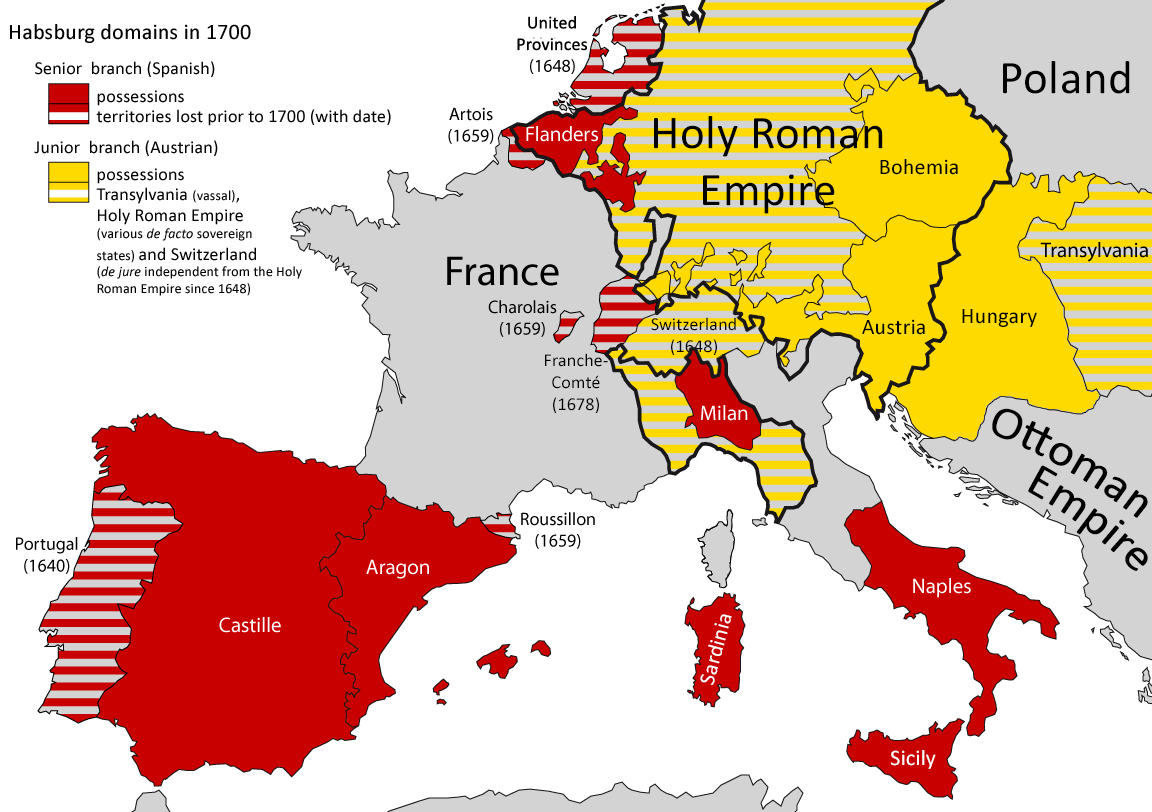

Spanish Absolutism, 1516-1659 | The Great Powers in Conflict

Spain in its Golden Age, 1516-1659, offers a case study of the clash between the ideal of absolutism and the persistence of the varied groups on which the monarchy sought to impose its centralized, standardizing rules. The reigns of its two hard-working monarchs, Charles V (r. 1516-1556) and Philip II, span almost the entire century.

-

The Catholic Monarchies: Spain and France | The Great Powers in Conflict

Such labels as Age of Absolutism and Age of Divine-Right Monarchy are frequently applied to the early modern centuries; over most of Europe the ultimate control of administration rested with a hereditary monarch who claimed a God-given right to make final decisions. But while the greater nobles were losing power and influence to the monarchy,…

-

The Wars of Philip II and the Dutch Revolt, 1556-1598 | The Great Powers in Conflict

In 1556 Charles V abdicated both his Spanish and imperial crowns and retired to a monastery, where he died two years later. His brother, who became Emperor Ferdinand I (r. 1556-1564), secured the Austrian Habsburg territories; his son, Philip II of Spain (r. 1556— 1598), added the Spanish lands overseas (Mexico, Peru, and in the…

-

Francis I versus Charles V, 1515-1559 | The Great Powers in Conflict

There were now two aggressors: the French house of Valois, still bent on expansion, and the house of Habsburg. When the Habsburg Charles V (who was Charles I in Spain), succeeded his grandfather Maximilian as emperor in 1519, he had inherited Spain, the Low Countries, the Habsburg lands in central Europe, the Holy Roman Empire,…

-

The Italian Wars of Charles VIII and Louis XII, 1483-1515 | The Great Powers in Conflict

Charles VIII of France (r. 1483-1498) continued Louis XI’s policy of extending the royal domain by marrying the heiress of the duchy of Brittany. Apparently secure on the home front, Charles decided to expand abroad. As the remote heir of the Angevins, Charles disputed the right of the Aragonese, then led by Ferdinand (1458-1494), to…

-

The Instruments of Foreign Policy | The Great Powers in Conflict

By 1500 almost all European sovereign states possessed, at least in rudimentary form, most of the social and political organs of a modern state. They had two essential instruments: a professional diplomatic service and a professional army. The fifteenth and sixteenth centuries saw the steady development of modern diplomatic agencies and methods.

-

Renaissance Monarchies, 1450-1650 | The Great Powers in Conflict

In early modern times, Western society was a group of states, each striving to grow, usually by annexing other states or at least bringing them under some sort of control. At any given moment some states were on the offensive, trying to gain land, power, and wealth; others were on the defensive, trying to preserve…

-

A Long Duree | The Great Powers in Conflict

In the long struggle between the European nations for hegemony, there was an enduring theme—a “long sixteenth century,” or long duree, of population growth and price inflation during which the Mediterranean basin largely remained the economic and military heart of Europe. In the past a steady increase in population tended to exceed the capacity of…

-

The Great Powers in Conflict

Here is no general agreement on which date, or even which development, best divides the medieval from the modern. Some make a strong case for a date associated with the emergence of the great, ambitious monarchs: Louis XI in France in 1461; or Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile, who were married in 1469;…

-

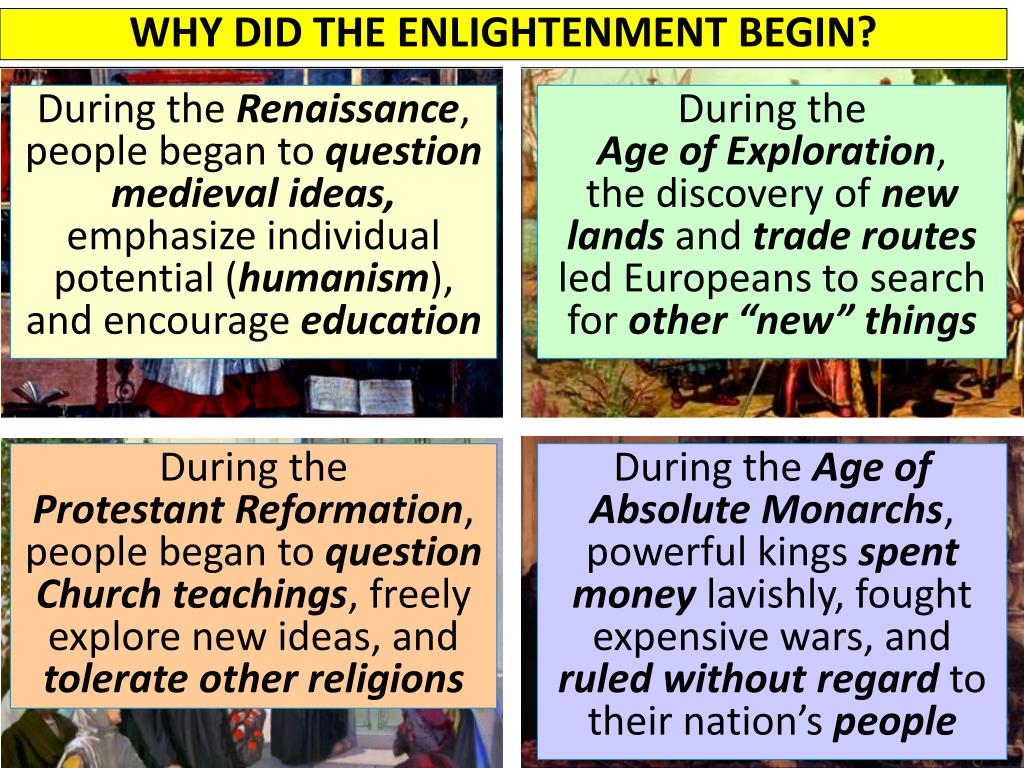

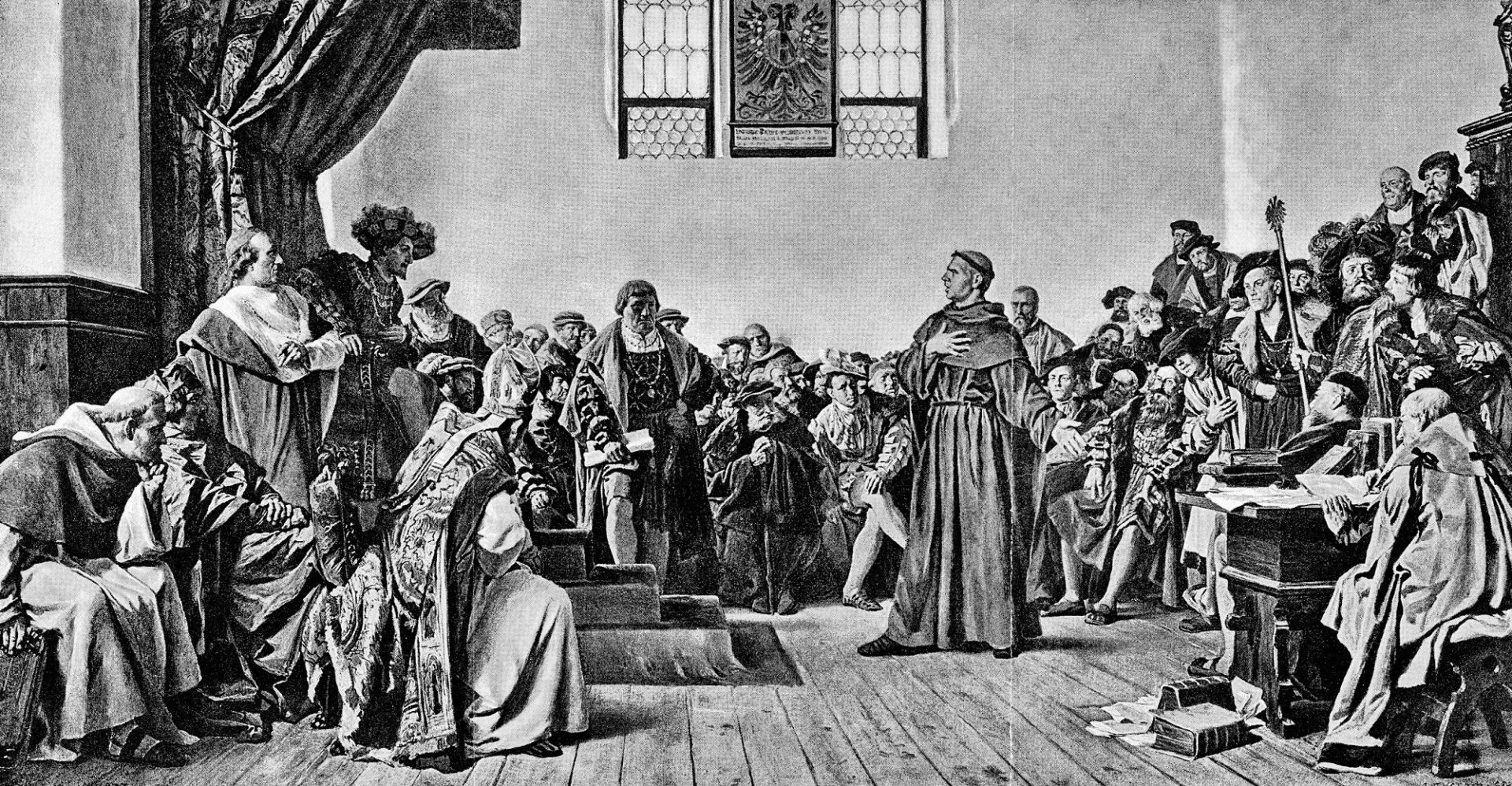

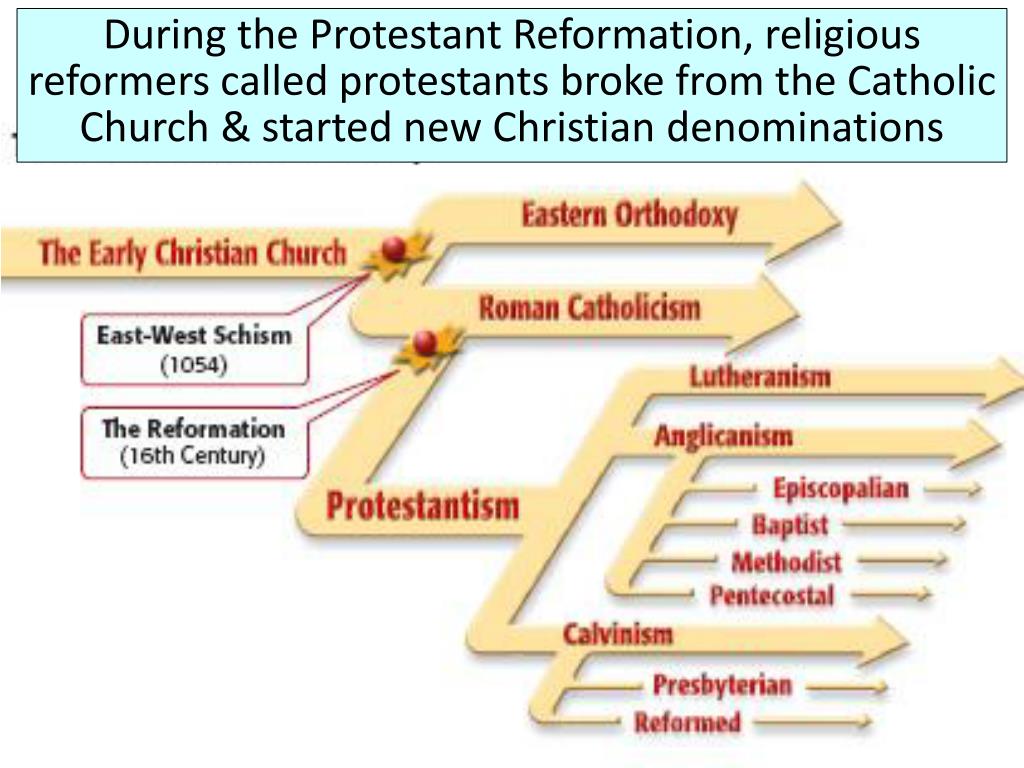

Summary | The Protestant Reformation

In 1517 Martin Luther touched off a revolution when he drew up Ninety-five Theses for debate. In them he questioned church practices, specifically the practice of granting indulgences—popularly believed to grant forgiveness of sin and remission of punishment. Luther himself had come to believe in the primacy of faith over good works and in the…

-

Nationalism, Modernity, and the Reformation | The Protestant Reformation

After the great break of the sixteenth century, both Protestantism and Catholicism became important elements in the formation of modern nationalism. Neither Protestants nor Catholics were always patriots. French Protestants sought help from the English enemy, and French Catholics from the Spanish enemy. But where a specific religion became identified with a given political unit,…

-

Conflicting Views of Protestantism | The Protestant Reformation

The German sociologist Max Weber explored this question in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, first published in 1904. What started Weber’s exploration was evidence suggesting that in his own day German Protestants had a proportionately greater interest in the world of business, and German Catholics a proportionately smaller interest, than their ratio…

-

How "Modern" Was Protestantism? | The Protestant Reformation

The Reformation has often been interpreted, especially by Protestants, as peculiarly modern, forward-looking, and democratic—as distinguished from the stagnant and class-conscious Middle Ages. This view seems to gain support from the fact that those parts of the West that in the last three centuries have been most prosperous, that have seemed to have worked out…

-

The Inquisition

In the sixteenth century the Inquisition inquired into the faith and correctness of view of many people who considered themselves to be Christians. In 1583 Domenico Scandella, called Menocchio (1532-1599), was denounced for heresy. Menocchio had been asked about the relationship of God to chaos, and he had answered “that they were never separated, that…

-

The Council of Trent, 1545-1564 | The Protestant Reformation

If anything, revulsion against the Protestant tendency toward the “priesthood of the believer” hardened Catholic doctrines into a firmer insistence on the miraculous power of the priesthood. Protestant variation promoted Catholic uniformity. Not even on indulgences did the church yield; interpreted as a spiritual rather than a monetary transaction, indulgences were reaffirmed by the Council…

-

The Jesuits and the Inquisition, 1540-1556 | The Protestant Reformation

The greatest of these clerical orders by far was the Society of Jesus, founded in 1540 by the Spaniard Ignatius Loyola (1491-1556). Loyola, who had been a soldier, turned to religion after receiving a painful wound in battle. From the first the Jesuits were the soldiery of the Catholic church; their leader bore the title…

-

The Catholic Reformation | The Protestant Reformation

The religious ferment from which Protestantism emerged was originally a ferment within the Catholic church, to which many who remained Catholics had contributed. Erasmus and other Christian humanists greatly influenced the early stages of what came to be called the Catholic Reformation. Particularly in Spain, but spreading throughout the Catholic world, there was a revival…

-

The Radicals | The Protestant Reformation

Among the radicals, preaching was even more important than in other forms of Protestantism, and more emotionally charged with hopes of heaven and fears of hell. Many sects expected an immediate Second Coming of Christ and an end of the material world. Many were economic equalitarians, communists of a sort; they did not share wealth,…

-

Calvinism and Predestination | The Protestant Reformation

For Calvinists the main theological concern was the problem of predestination against free will. The problem arose from the concept that God is all-powerful, all-good, all- knowing; this being so, he must determine all that happens, even willing that the sinner must sin. For if he did not so will, a person would be doing…

-

The Conservative Churches | The Protestant Reformation

The divergent beliefs and practices that separated the Protestant churches one from another may be arranged most conveniently in order of their theological distance from Catholicism. The Church of England managed to contain almost the whole Protestant range, from High Church to extreme Low Church.

-

Common Denominators of Protestant Beliefs and Practices | The Protestant Reformation

There were certain common beliefs and practices that linked all Protestant sects and set them apart from Catholicism. The first of these common denominators was repudiation of Rome’s claim to be the one true faith. The difficulty here was that each Protestant sect initially considered itself to be the one true faith, the legitimate successor…

-

Anabaptists and Other Radicals, 1521-1604 | The Protestant Reformation

Socially and intellectually less “respectable” than the established Lutheran and Anglican churches or the sober Calvinists was a range of radical sects, the left wing of the Protestant revolution. In the sixteenth century most of these were known as Anabaptists (from the Greek for “baptizing again”).

-

Protestant Founders: King Henry VIII, 1509-1547 | The Protestant Reformation

In England, the Reformation arose from the desire of King Henry VIII (b. 1491; r. 1509-1547) to put aside his wife, Catherine of Aragon (1485-1536) because she had not given him a male heir. In 1533 Henry married Anne Boleyn (1507-1536), whom he had made pregnant; Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556), the archbishop of Canterbury, annulled the…

-

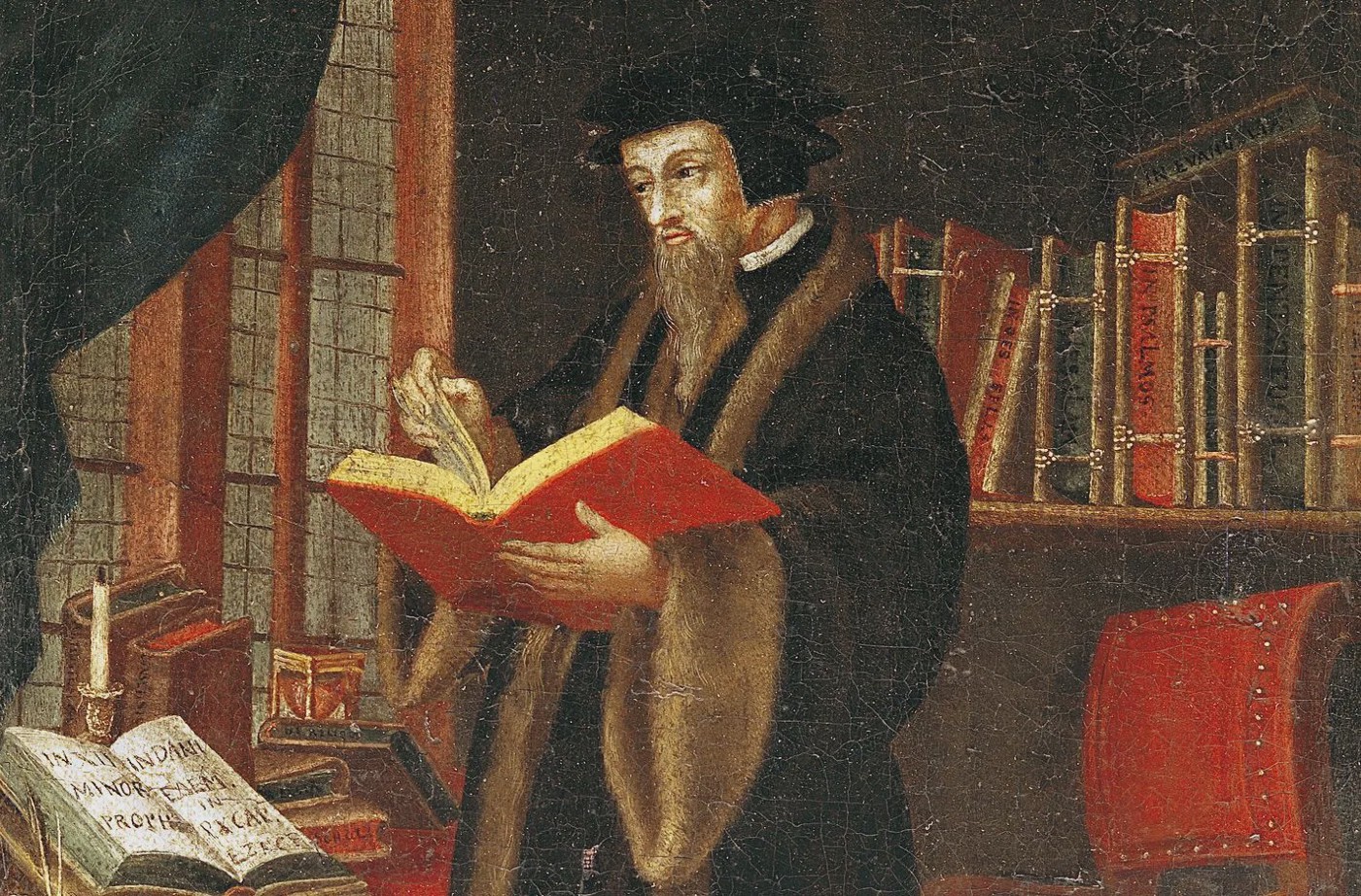

Protestant Founders: John Calvin, 1509-1564 | The Protestant Reformation

Another Swiss city ripe for Protestant domination was Geneva. A new religious and political regime developed there under the leadership of the French-born Jean Chauvin—John Calvin. Calvin shaped the Protestant movement as a faith and a way of life in a manner that gave it a more broadly European basis. Both Calvin and Zwingli worked…

-

Protestant Founders: Ulrich Zwingli, 1484-1531 | The Protestant Reformation

There were many other figures who attacked the Church of Rome. Some of these, like Thomas Miintzer (c. 1470— 1525), strongly opposed Luther’s views. But among the many founders of what came to be known as Protestantism, the first in sequence was Ulrich Zwingli (1484– 1531), the first in importance John Calvin (1509-1564).

-

Martin Luther: A Conservative Revolutionary | The Protestant Reformation

Luther did not push his doctrines of justification by faith and the priesthood of all believers to their logical conclusion, namely, that if religion is wholly a matter between “man and God,” an organized church would be unnecessary. When radical reformers inspired by Luther attempted to apply these concepts to the churches of Saxony in…

A History of Civilization