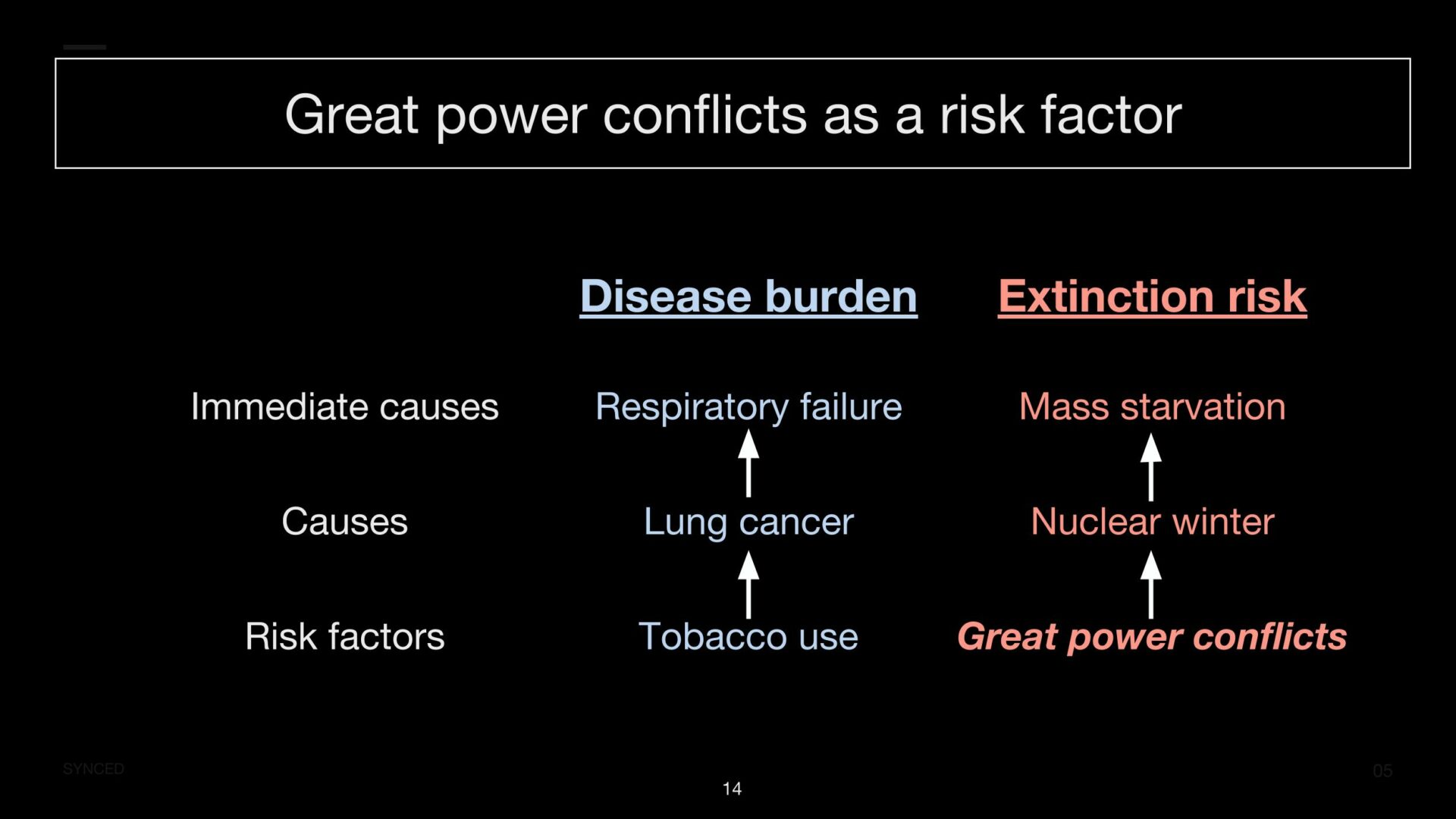

The Great Powers in Conflict

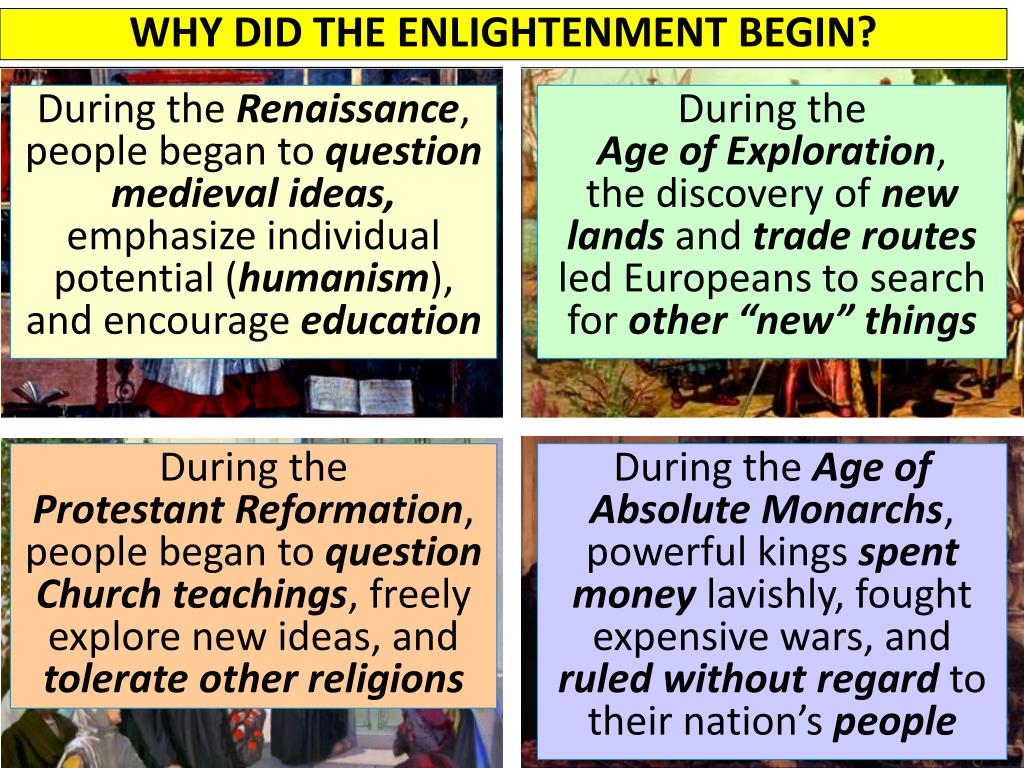

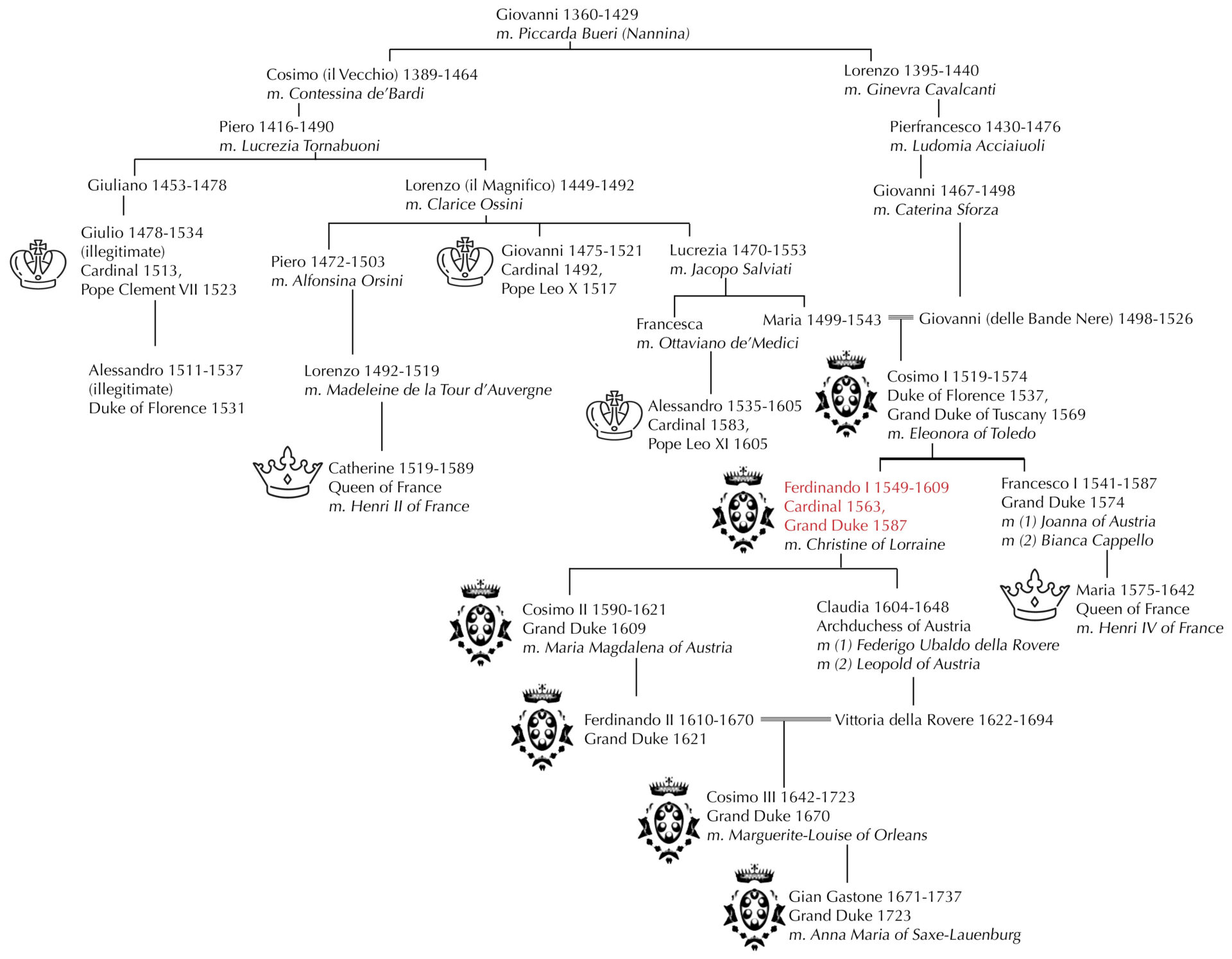

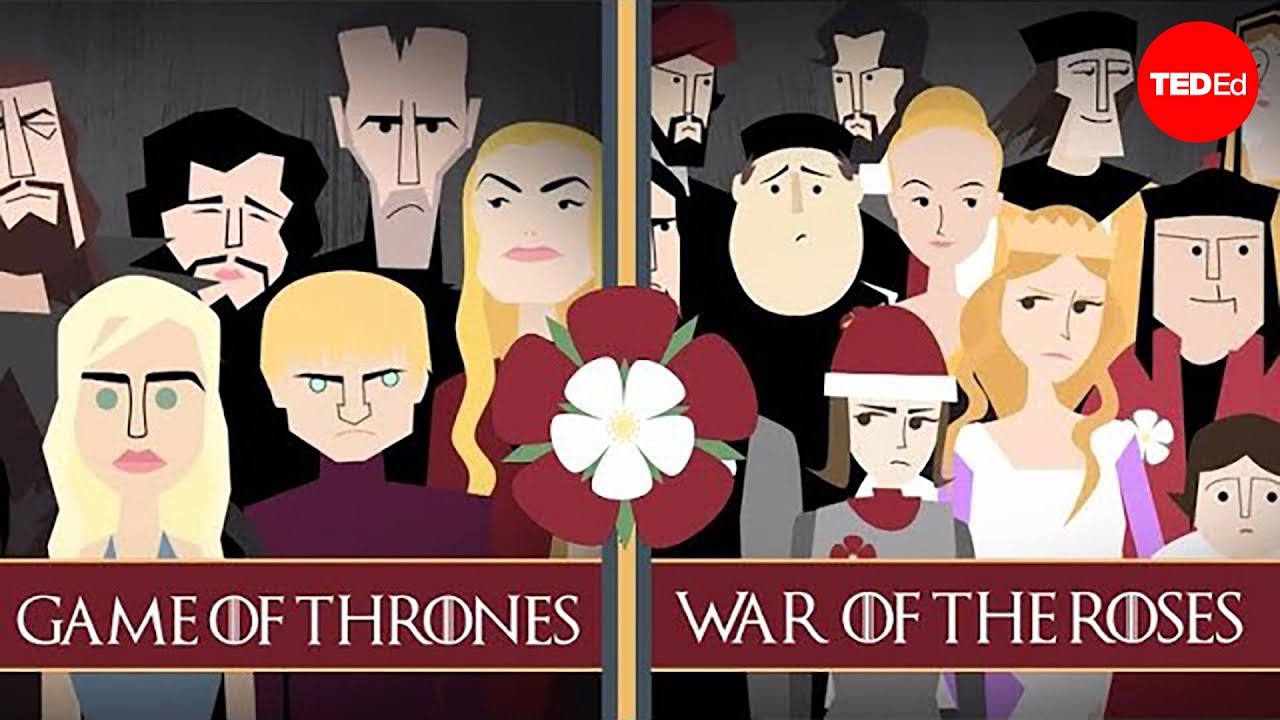

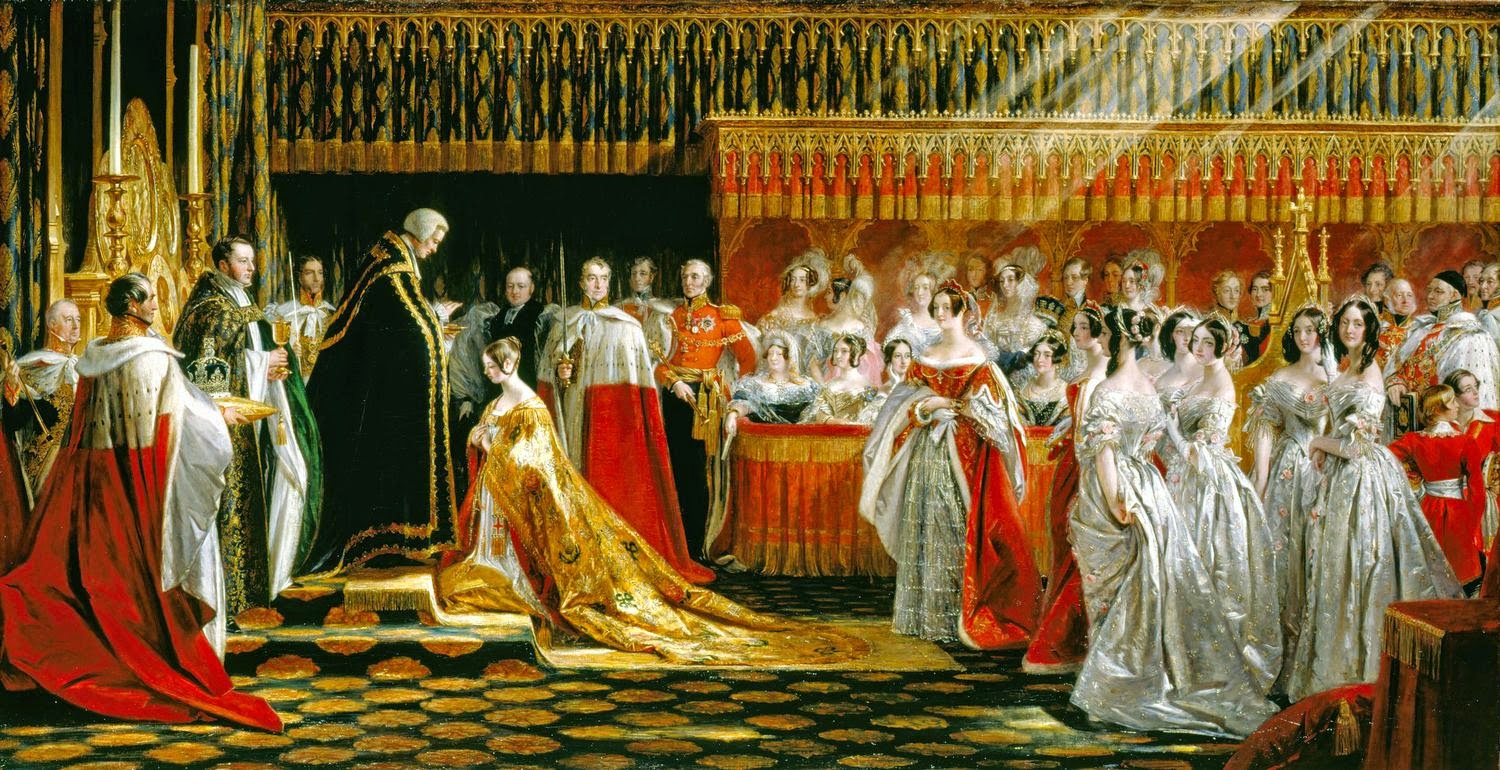

Here is no general agreement on which date, or even which development, best divides the medieval from the modern. Some make a strong case for a date associated with the emergence of the great, ambitious monarchs: Louis XI in France in 1461; or Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile, who were married in 1469; or the advent of Henry VII and the Tudors in England in 1485.

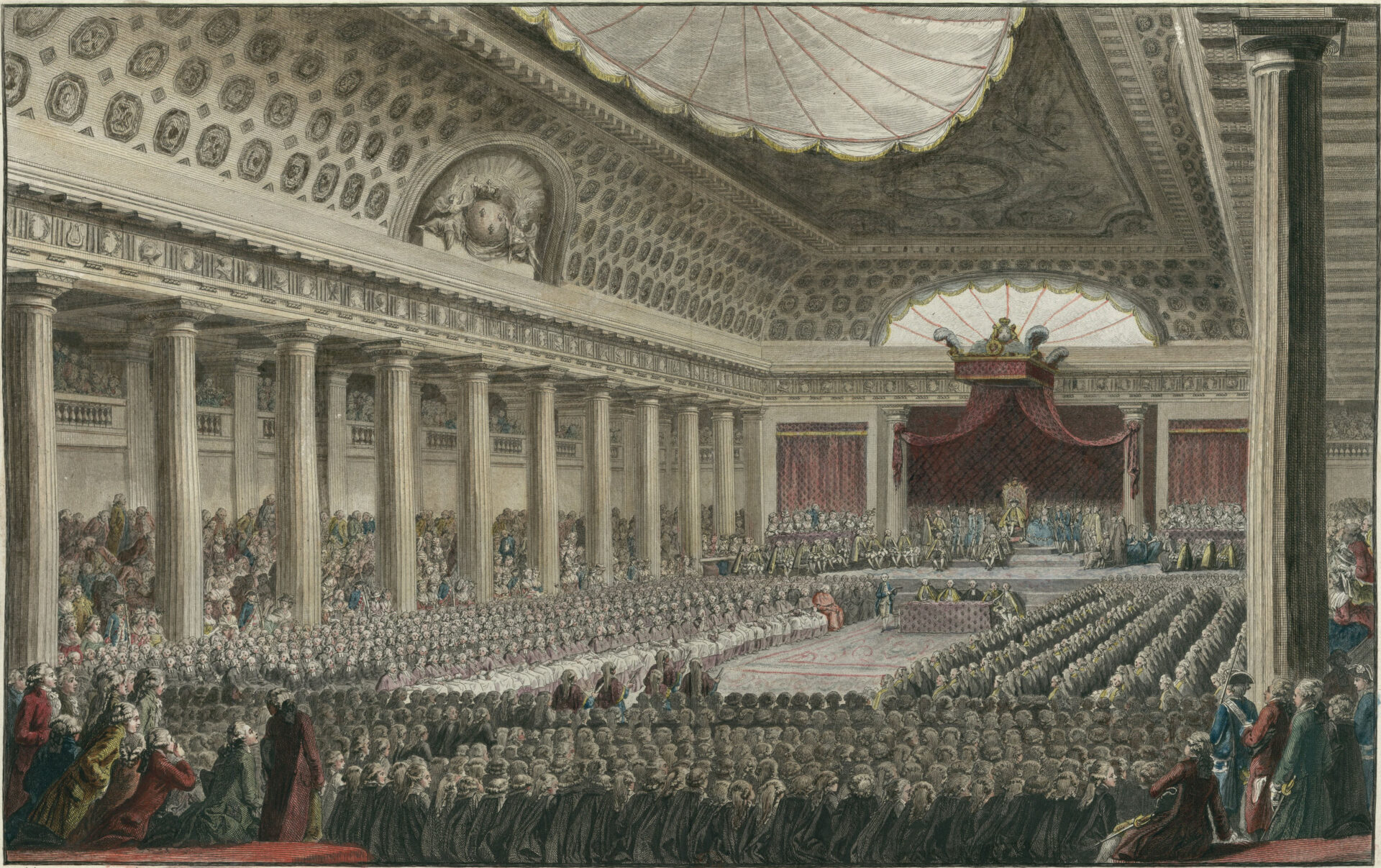

Scholars who value international relations tend to choose 1494, when Charles VIII of France began what is often called “the first modern war” by leading his army over the Alps to Italy.