Henry IV owed his position in part to confirmation by Parliament was sensitive about allowing any assertion of royal authority. Moreover, Henry faced a series of revolts. The last years of his reign were troubled by poor health and by the hostility of his son, Henry V (r. 1413-1422). Henry V renewed the Hundred Years’ War with spectacular victories and reasserted royal power at home, tempered by his need to secure parliamentary support to finance his French campaigns. He also vigorously persecuted the Lollards.

The untimely death of Henry V in 1422 ended the brief period of Lancastrian success, for it brought to the throne Henry VI (r. 1422-1461), a nine-month-old infant who proved mentally unstable as he grew up. As English forces were defeated in the last campaigns of the Hundred Years’ War, the feebleness of Henry VI strengthened both the hand of Parliament and the growth of private armed retainers.

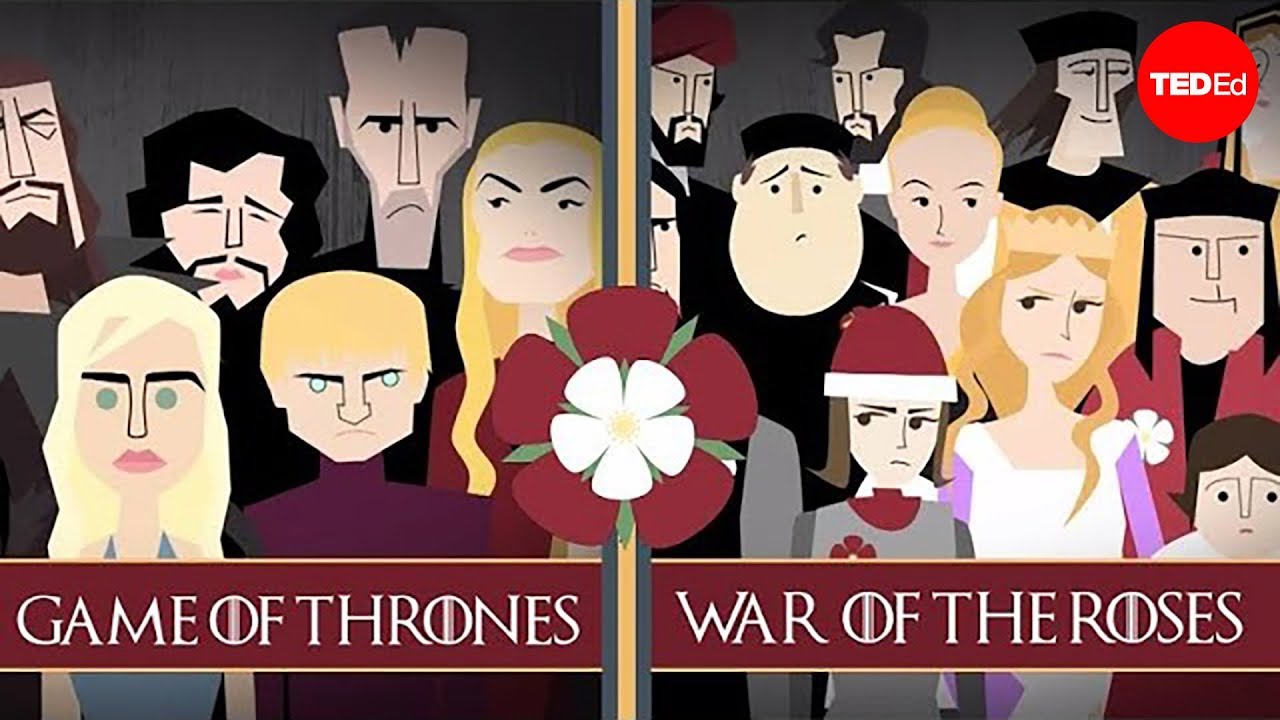

While corrupt noble factions competed for control of government, a quarrel broke out between Henry VI’s queen, Margaret of Anjou, and her English allies on the one side, and on the other, Richard, duke of York, once regent of France and now heir to the English throne. The quarrel led directly to the Wars of the Roses (1455-1485), so named for the red rose, badge of the House of Lancaster, and the white rose, badge of the House of York.

In thirty years of dreary, sporadic fighting, Parliament became the tool of rival factions, and the kingdom changed hands repeatedly. In 1460 Richard of York was killed, and the ambitious earl of Warwick took over the leadership of the Yorkist cause. Warwick forced the abdication of Henry VI and placed on the throne the son of Richard of York, Edward IV (r. 1461-1483). King and kingmaker soon fell out, and Warwick briefly restored the house of Lancaster to the throne (1470-1471). Edward IV quickly regained control, however, and Henry VI and Warwick were killed. With Edward securely established, firm royal government returned to England.

Again, however, the prospect of stability faded, for Edward IV died in 1483. His twelve-year-old son, Edward V, was soon pushed aside by his guardian and uncle, Richard III (r. 148-1485), last of the Yorkist kings. Able, courageous, and ruthless, Richard III continues to be the focus of much controversy. There is still debate over whether Richard was responsible for the death of Edward V and his younger brother.

In any case, factional strife flared up again as Richard’s opponents found a champion in the Lancastrian leader Henry Tudor. In 1485, on Bosworth Field, Richard III was slain, and the Wars of the Roses came to an end. The battle gave England a new monarch, Henry VII, and a new dynasty, the Tudors.