-

Martin Luther: A Conservative Revolutionary | The Protestant Reformation

Luther did not push his doctrines of justification by faith and the priesthood of all believers to their logical conclusion, namely, that if religion is wholly a matter between “man and God,” an organized church would be unnecessary. When radical reformers inspired by Luther attempted to apply these concepts to the churches of Saxony in…

-

Martin Luther on Christian Liberty

In 1520 Martin Luther wrote On Christian Liberty. Considered to be “the most beautiful” of Luther’s writings, the Treatise on the Liberty of a Christian Man (its correct formal title) was an affirmation rather than a protest. Luther said he was sending his long essay as a gift to Pope Leo X.

-

Reasons for Martin Luther’s Success | The Protestant Reformation

Fundamentally Luther succeeded because his ideas appealed to people of all classes. In its maturity his theology was seen as revolutionary in economic, social, and political—as well as intellectual and doctrinal ways. The printing press quickly made Luther’s ideas more accessible and assured that they were recorded in permanent forms. Political circumstances also favored Luther…

-

Protestant Founders: Martin Luther, 1483-1546 | The Protestant Reformation

Martin Luther (1483-1546) was a professor of theology the University of Wittenberg. In 1517 he was undergoing a great religious awakening. Luther’s father had sent him to the University of Erfurt, then the most prestigious in Germany, to study law. Luther yearned instead to enter the religious life. On his way back to Erfurt he…

-

The Protestant Reformation

In October 1517, at Wittenberg in the German electorate of Saxony, the Augustinian monk Martin Luther drew up ninety-five theses for theological disputation and thereby touched off the sequence of events that produced the Protestant Reformation. Luther’s provocative theses were soon translated from Latin into German and, when printed, were read and debated far beyond…

-

Summary | The Renaissance

Scholars have debated what the Renaissance was and when it began. However, most accept that it began in Italy about 1300 and lasted for about three centuries. The outpouring of intellectual and artistic energy was not only marked by a revival of interest in classical Greek and Roman values but also owed a debt to…

-

The Courtier

The Italian Baldassare Castiglione (1478-1529) was said to be “one of the finest gentlemen in the world.

-

The Artist’s Life

Benvenuto Cellini’s fame rests as much on his Autobiography as on his art. Begun in Florence in 1558, it is filled with court gossip, attacks on fellow artists, and accounts of Cellini’s often riotous life. It could take him months, even years, to complete a single commissioned work of art, for he faced many distractions.…

-

The Art of Daily Living | The Renaissance

Indoors, Renaissance buildings reflected the improving standard of life among the affluent. Smaller rooms were easier to heat than the vast drafty halls of the Middle Ages, and items of furniture began to multiply beyond the medieval complement of built-in beds, benches, cupboards, and tables. Although chairs were still largely reserved for the master of…

-

Architecture | The Renaissance

In 1546, at the age of seventy, Michelangelo agreed to become the chief architect of St. Peter’s in Rome. St. Peter’s exemplifies many of the features that distinguish Renaissance architecture from Gothic. Gothic cathedrals were topped by great spires and towers; Sc. Peter’s was crowned by Michelangelo’s massive dome, which rises 435 feet above the…

-

Sculpture | The Renaissance

Renaissance sculpture and painting were closely related, and Italian pictures owed some of their three-dimensional quality to the artists’ study of sculpture. The first Renaissance sculptor was Donatello (1386-1466), whose statue of the condottiere Gattamelata in Padua was even then a landmark in the history of art.

-

Painting in Northern Europe | The Renaissance

In northern Europe the masters of the fifteenth century were influenced by their Gothic traditions as well as by Titian and other Italians. The ranking northern painters included two Germans, Albrecht Durer (1471-1528) and Hans Holbein (c. 1496-1543), and two from the Low Countries, Hieronymus Bosch (c. 1450-1516) and Pieter Brueghel (c. 1525-1569).

-

Renaissance Satire

The following is an excerpt from a satirical work written in 1515 and titled The Letters of Obscure Men. The two authors were Ulrich von Hutten and Crotus Rubeanus. For you must know that we were lately sitting in an inn, having our supper, and were eating eggs, when on opening one, I saw that…

-

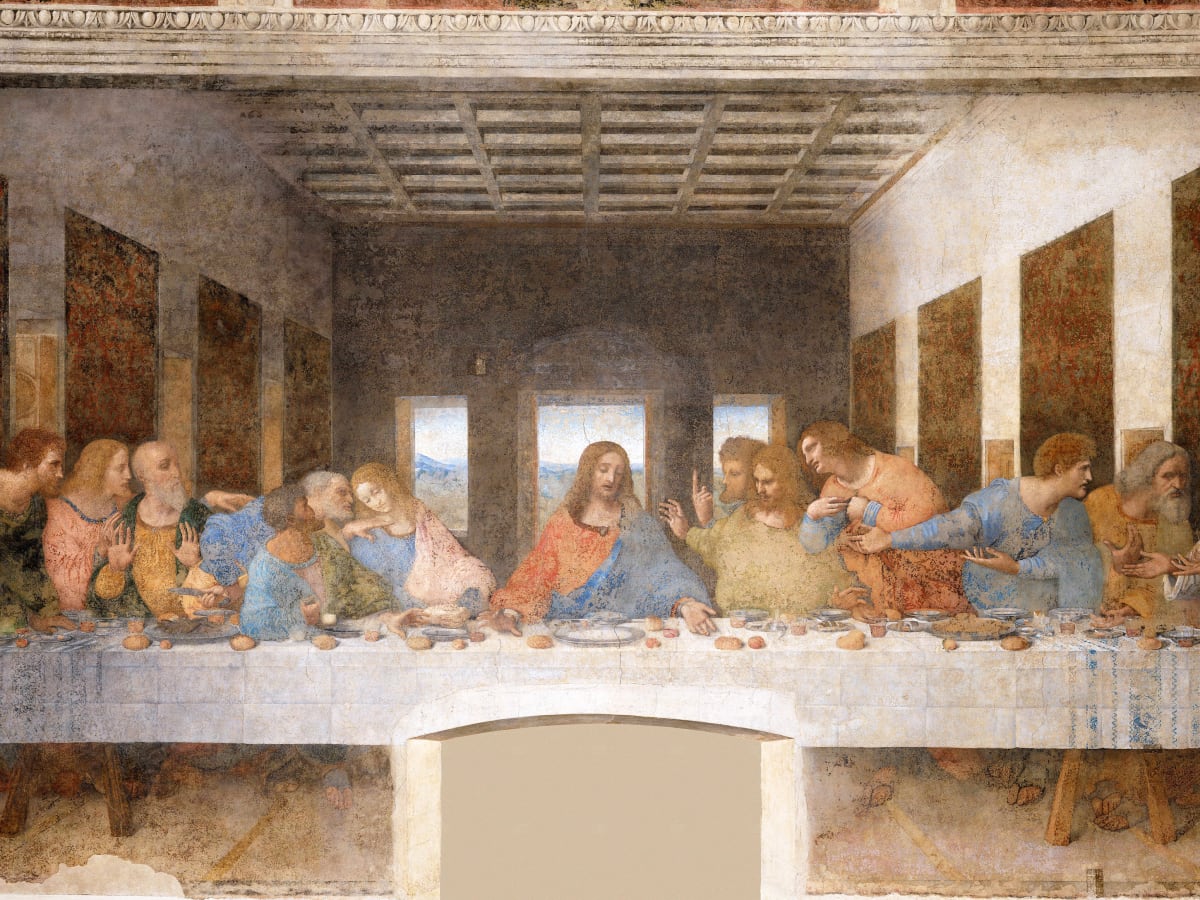

The Fine Arts | The Renaissance

Even more than the writers and preachers of the Renaissance, its artists displayed an extraordinary range of originality in their interests and talents. They found patrons both among the princes of the church and among merchant princes, condottieri, and secular rulers. They took as subjects their own patrons and the pagan gods and heroes of…

-

The Renaissance and the Church | The Renaissance

Renaissance science as a whole aroused discord within the church. Even though Copernicus dedicated his great book to the pope, Christendom did not welcome a theory that questioned the belief in an earth-centered, human-centered universe. By Copernicus’s time, Western Christendom was preoccupied by its division into the warring factions of Catholic and Protestant. To what…

-

Music | The Renaissance

In the medieval curriculum music was grouped with the sciences because mathematics underlies musical theory and notation. The mainstay of medieval sacred music was the Gregorian chant or plainsong, which relied on a single voice. At the close of the Middle Ages musicians in the Low Countries and northern France developed the technique of polyphony,…

-

Astronomy | The Renaissance

The year 1543 marked the publication of Copernicus’s De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (Concerning the Revolutions of Heavenly Bodies). Born in Poland of German extraction, Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543) studied law and medicine at Padua and other Italian universities and spent thirty years as canon of a cathedral near Danzig. His work in mathematics and astronomy led…

-

Invention, Technology, Medicine | The Renaissance

The most important invention of the Renaissance—the technology for printing books—furnishes a case history of how many individual advances contribute to an end result. The revolution in book production began in the twelfth century, when Muslims in Spain introduced a technique first developed by the Chinese in the second century and began to make paper…

-

Science and Religion | The Renaissance

Humanism both aided and impeded the advance of science. The Renaissance was less a dramatic rebirth of science than an age of preparation for the scientific revolution that was to come in the seventeenth century. The major contribution of the humanists was increased availability of ancient scientific authorities, as works by Galen, Ptolemy, Archimedes, and…

-

Classical Scholarship | The Renaissance

The men of letters of this period may be divided into three groups: First were the conservers of classical culture, heirs of Petrarch’s humanistic enthusiasm for the classical past; second were the vernacular writers who took the path marked out by the Decameron, from Chaucer at the close of the fourteenth century down to Rabelais…

-

Writers of the Early Italian Renaissance | The Renaissance

Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) was the first major Italian writer to embody some of the qualities that were to characterize Renaissance literature. Much of Dante’s writing and outlook bore the stamp of the Middle Ages, and the grand theme of the Divine Comedy was medieval, the chivalric concept of disembodied love inspiring his devotion to Beatrice,…

-

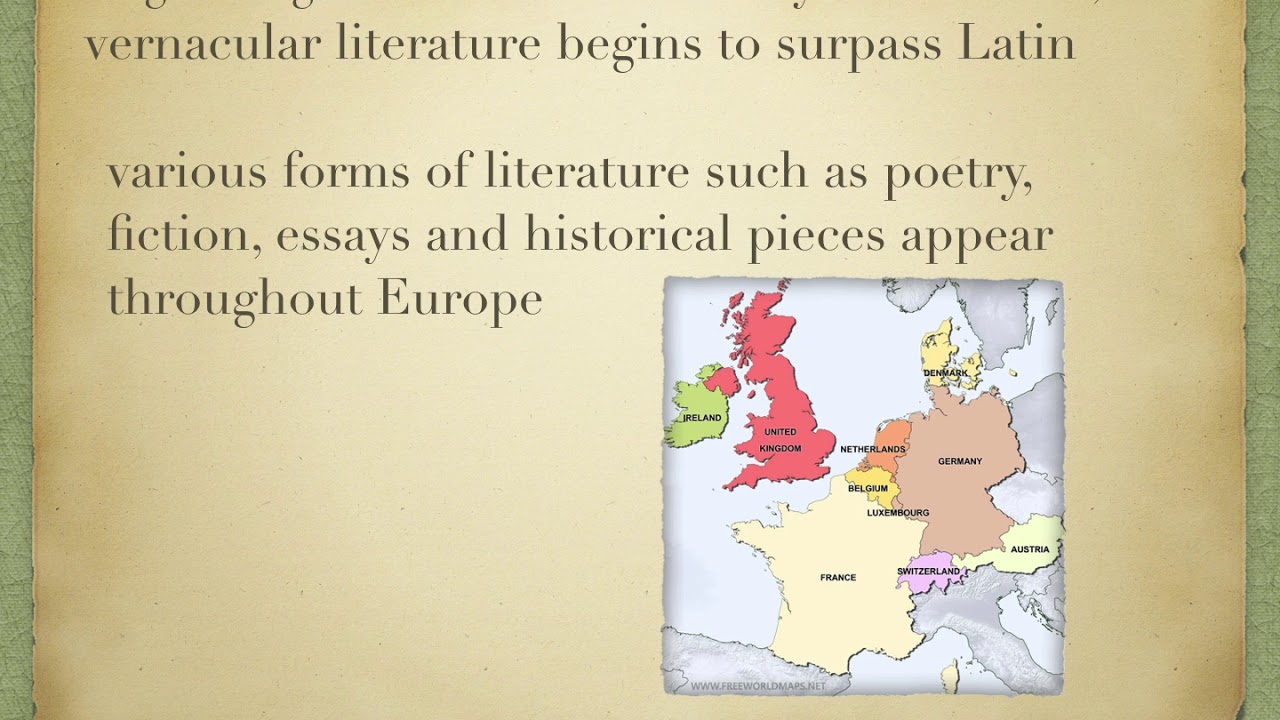

The Vernaculars and Latin | The Renaissance

The vernaculars of the western European countries emerged gradually, first as the spoken languages of the people, then as vehicles for popular writing, finally achieving official recognition. Many vernaculars—Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and French—developed from Latin; these were the Romance (Roman) languages. Castilian, the core of modern literary Spanish, attained official status in the thirteenth century…

-

Printing, Thought, and Literature | The Renaissance

The communications revolution brought on by the printing press, the enormous significance of the book as a force for change, the simple fact that printing preceded the Protestant revolt on which the Reformation fed are all aspects of a profound shift in perspective that, perhaps more than any other change, defines the transition between medieval…

-

Town and Countryside | The Renaissance

Augsburg’s total population at the height of Fugger power probably never exceeded 20,000. One set of estimates for the fourteenth century puts the population of Venice, Florence, and Paris in the vicinity of 100,000 each; that of Genoa, Milan, Barcelona, and London at about 50,000; and that of the biggest Hanseatic and Flemish towns between…

-

Banking | The Renaissance

The expansion of trade and industry promoted the rise of banking. The risks of lending were great, but so, too, were the potential profits. In 1420 the Florentine government vainly tried to put a ceiling of 20 percent on interest rates. Bankers were money changers, for only experts could establish the relative value of the…

-

Industry | The Renaissance

The expansion of trade stimulated industry. The towns of Flanders had developed the weaving of woolen cloth in the thirteenth century, with many workers and high profits. In the early fourteenth century perhaps two hundred masters controlled the wool guild of Florence, which produced nearly 100,000 pieces of cloth annually and employed 30,000 men.

-

Trade | The Renaissance

The areas of Europe to the west of the Adriatic Sea and the Elbe River were changing from the more subsistence- oriented economy of the early Middle Ages to a money economy, from an economy based in good measure on home-grown produce paid for in kind to one relying heavily on imports paid for in…

-

The Renaissance

Renaissance rebirth is the name traditionally bestowed upon the remarkable outpouring of intellectual and artistic energy and talent that accompanied the passage of Europe from the Middle Ages to the modern epoch. Yet “Renaissance” to a large extent was the creation of nineteenth century scholars who, looking back on the intense flowering of culture, sought…

-

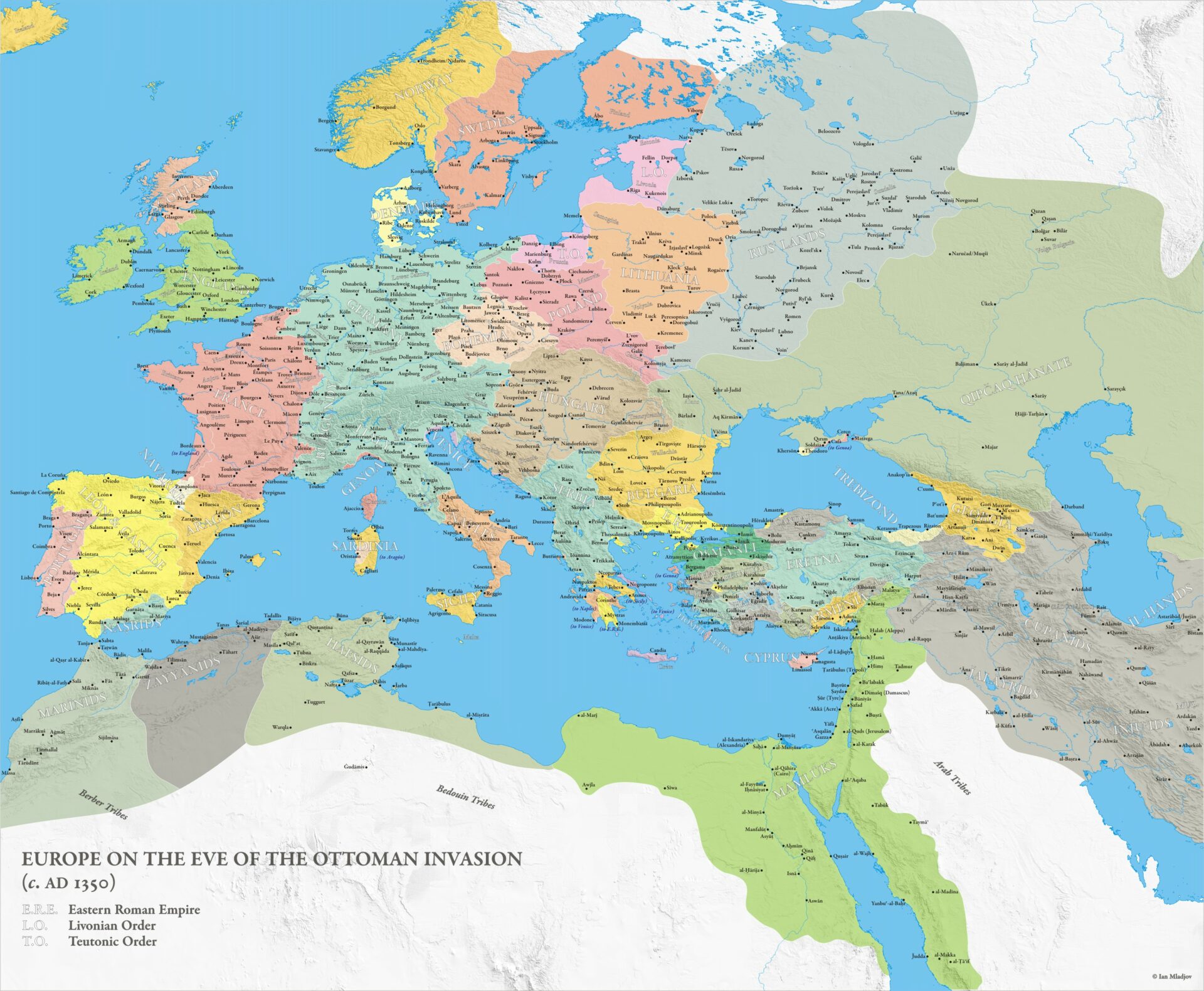

Summary | The Rise of the Nation

The transition from medieval to modern times was marked by the consolidation of royal power, the decline of serfdom, the revolt against the medieval church, and the increasing importance of a money economy. These changes were hastened by the calamity and hardships of the late Middle Ages, including the Hundred Years’ War, the Black Death,…

-

Machiavelli on the Church

Machiavelli blamed the Italians’ loss of civic spirit on the church, attacked the temporal interests of the papacy for preventing Italian unity, and questioned the values of Christianity itself. Machiavelli evidently believed that the purpose of government was less to prepare people for the City of God than to make them upstanding citizens of this…

-

"The School of Europe" | The Rise of the Nation

The Italian states of the fifteenth century have been called “the school of Europe,” instructing the rest of the Continent in the new realistic ways of power politics. Despots like Il Moro, Cesare Borgia, Lorenzo the Magnificent, and the oligarchs of Venice might well have given lessons in statecraft to Henry VII of England or…

-

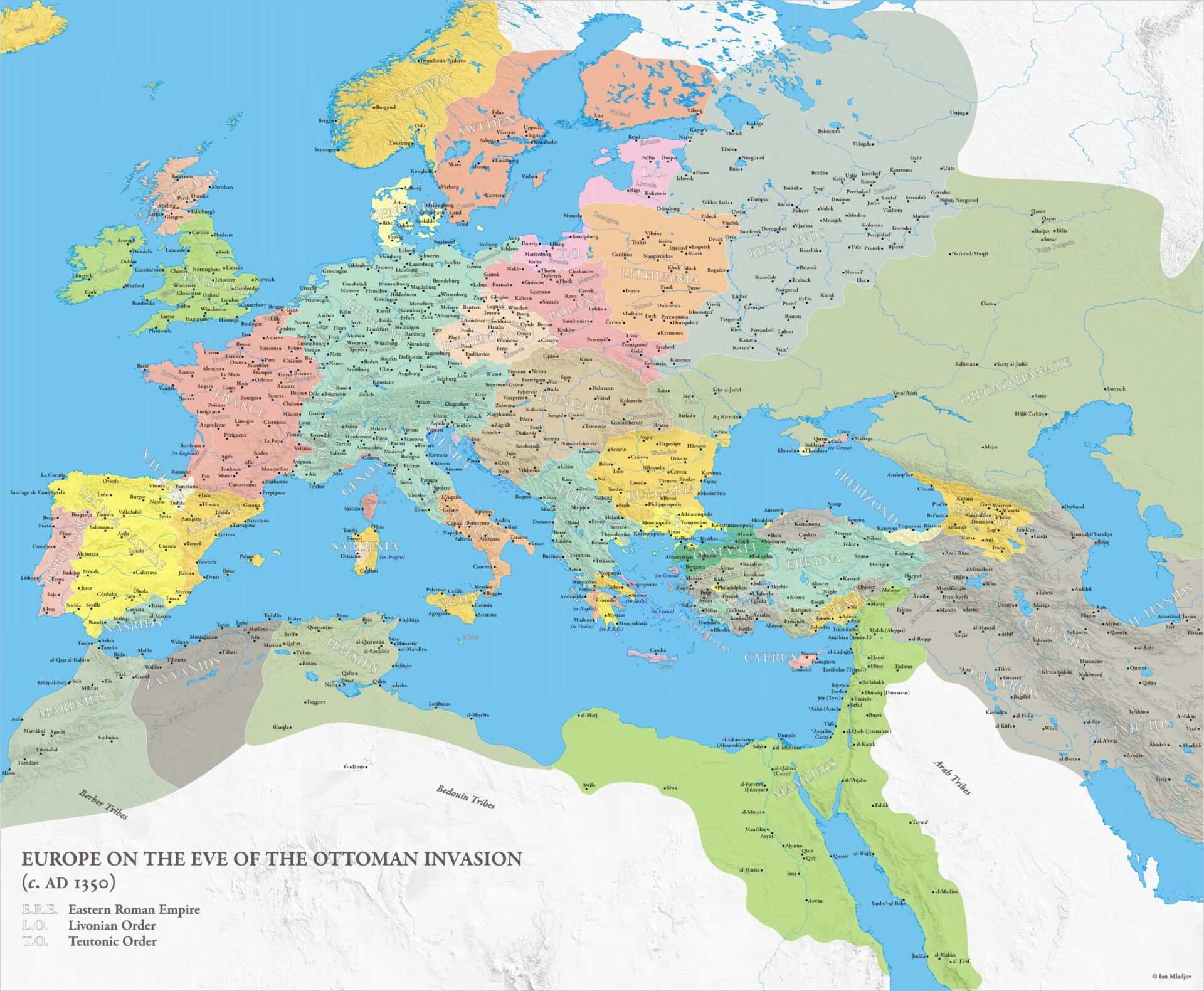

Venice in the Fifteenth Century | The Rise of the Nation

The third great north Italian state, Venice, enjoyed a political stability that contrasted with the turbulence of Milan and Florence. By the fifteenth century the Republic of Saint Mark, as it was called, was in fact an empire that controlled the lower Po valley on the Italian mainland, the Dalmatian coast of the Adriatic, the…

-

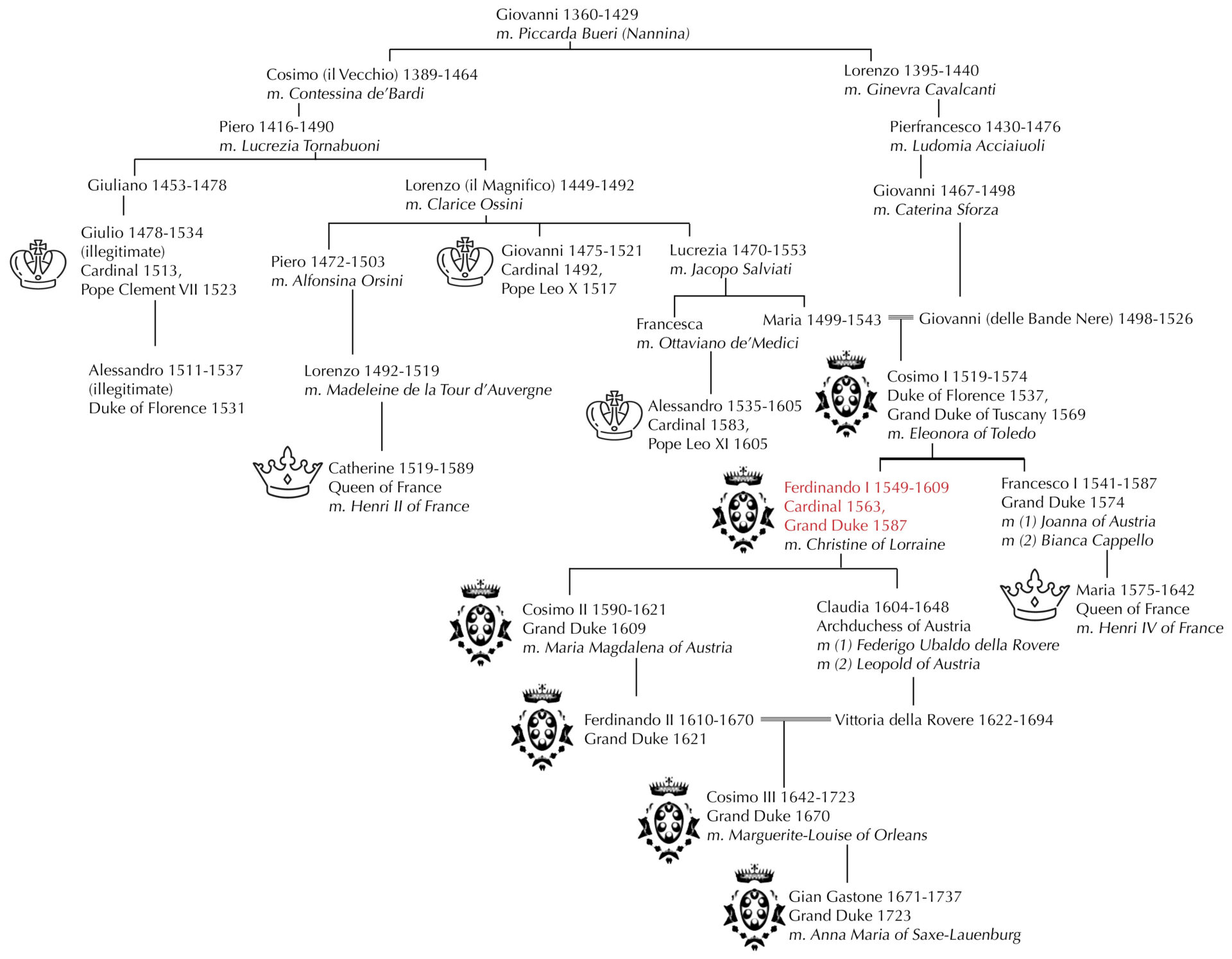

Florence, to 1569 | The Rise of the Nation

The Republic of Florence, like that of Milan, was a fragile combination of aristocratic and democratic elements. It was badly shaken by Guelf-Ghibelline rivalries and by the emergence of an ambitious wealthy class of bankers and merchants. In the twelfth century the commune had acquired a dominant position.

-

Milan, 1277-1535 | The Rise of the Nation

Milan lay in the midst of the fertile plain of Lombardy. It was the terminus of trade routes from northern Europe and was also a textile and metalworking center.

-

The Princes and the Empire, 1254-1493 | The Rise of the Nation

The imperial title survived. It went to Rudolf of Habsburg (r. 1273-1291), whose estates lay mostly in Switzerland. Rudolf wanted to establish a hereditary monarchy for his family and make this monarchy as rich and as powerful as possible. He added Austria to the family holdings, and his descendants ruled at Vienna until 1918. Rudolf…

-

Particularism and Germany and Italy | The Rise of the Nation

Power in Germany shifted steadily from the emperor to the princes of the particular states. For almost two decades, there was no emperor at all. This was the Great Interregnum (1254-1273), following the death of the last Hohenstaufen king, Conrad IV. During this time the princes grew even stronger at the expense of the monarchy,…

-

Spain, to 1492 | The Rise of the Nation

The decisive event in the early medieval history of the Iberian peninsula was the conquest by the Muslims, who brought almost the whole of the peninsula under their control. In the eighth and ninth centuries, Christian communities free of Muslim domination survived only in the extreme north.

-

Henry VII, 1485-1509 | The Rise of the Nation

Henry VII (r. 1485-1509) was descended from a bastard branch of the Lancastrian family. His right to be king, however, derived not from this tenuous hereditary claim but from his victory at Bosworth and a subsequent act of Parliament. The new monarch had excellent qualifications for the job of tidying up after the divisiveness of…

-

Lancaster and York, 1399-1485 | The Rise of the Nation

Henry IV owed his position in part to confirmation by Parliament was sensitive about allowing any assertion of royal authority. Moreover, Henry faced a series of revolts. The last years of his reign were troubled by poor health and by the hostility of his son, Henry V (r. 1413-1422). Henry V renewed the Hundred Years’…

-

Richard II and Bastard Feudalism, 1377-1399 | The Rise of the Nation

When Edward III died, his ten-year-old grandson succeeded as Richard II (r. 1377-1399). Richard’s reign was marked by mounting factionalism and peasant discontent. Both conflicts strongly resembled their French counterparts—the strife between Burgundy and Armagnac, and the Jacquerie of 1358. Just as the Jacquerie opposed attempts to regulate life in ways ultimately bound to benefit…

-

Piers the Plowman

The author of Piers Plowman was a popular writer roughly contemporary with Chaucer. The poem is a series of allegorical dreams that show the relationship of the individual to society in the fourteenth century. Piers, a simple plowman who works because he finds it good to do so, encounters lust, sloth, and greed around him.…

-

England: Edward II and Edward III, 1307-1377 | The Rise of the Nation

England was also emerging as a national monarchy. Bastard feudalism flourished until Edward IV and Henry VII reasserted royal power in the later fifteenth century, much as Louis XI did in France. But however close the parallels between the two countries, there was also an all- important difference. Whereas the French Estates General was becoming…

-

King Louis XI

A Fleming, Philippe de Commynes (c. 1445-1511), drew a portrait of Louis XI in his Memoires, a notable work of contemporaneous history.

-

The Burgundian Threat and King Louis XI, 1419-1483 | The Rise of the Nation

Against one set of enemies, however, Charles VII was not successful—his rebellious vassals, many of them beneficiaries of the new bastard feudalism, who still controlled nearly half of the kingdom. The most powerful of these vassals was the duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good (r. 1419-1467), whose authority extended to Flanders and other major portions…

-

Bias in Place Names

Not only do historic place names change, but places often simultaneously have two or more names and pronunciations. For example, Biscay Bay, referred to in the text, is the English form for Viscaya, its Spanish name; Napoli is the Italian form for Naples. Were this book written in a language other than English, these other…

-

Burgundians and Armagnacs, 1380-1467 | The Rise of the Nation

The new king, Charles VI (1380-1422), was intermittently insane. During his reign the monarchy was threatened by the disastrous results of the earlier royal policy of assigning provinces called apanages to the male members of the royal family. Such a relative might himself be loyal, but within a generation or two his heirs would be…

-

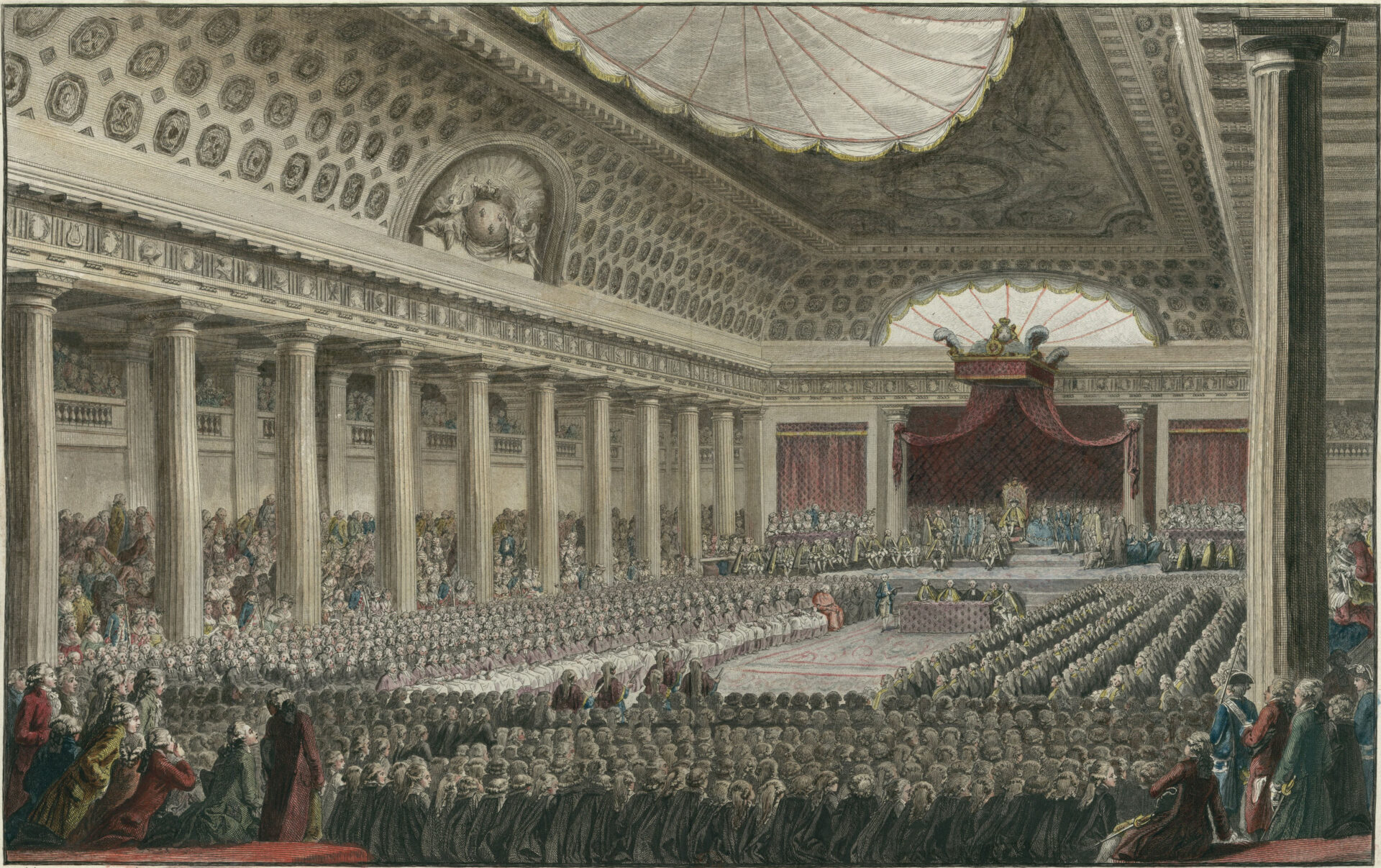

The Estates General | The Rise of the Nation

In these years the French monarchy faced increasingly hostile criticism at home. When summoned in 1355 to consent to a tax, the Estates General insisted on determining its form—a general levy on sales and a special levy on salt—and demanded also that their representatives rather than those of the Crown act as collectors.

-

The Outbreak of the Hundred Years’ War, 1337 | The Rise of the Nation

The nominal cause of the war was a dispute over the succession to the French throne. For more than three hundred years son had followed father as king of France. This remarkable succession ended with the three sons of Philip the Fair, none of whom fathered a son who survived infancy. The crown then passed…

-

The Emerging National Monarchies | The Rise of the Nation

At the death of Philip the Fair in 1314, the Capetian monarchy of France seemed to be evolving into a new professional institution staffed by efficient and loyal bureaucrats. Philip Augustus, Louis IX, and Philip the Fair had all consolidated royal power at the expense of their feudal vassals, who included the kings of England.…

-

A World Turned Upside Down | The Rise of the Nation

During the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries old forms and attitudes persisted in Western politics but became less flexible and less creative. The Holy Roman emperor Henry VII in the early 1300s sought to straighten out the affairs of Italy in the old Ghibelline tradition, even though he had few of the resources that had been…

-

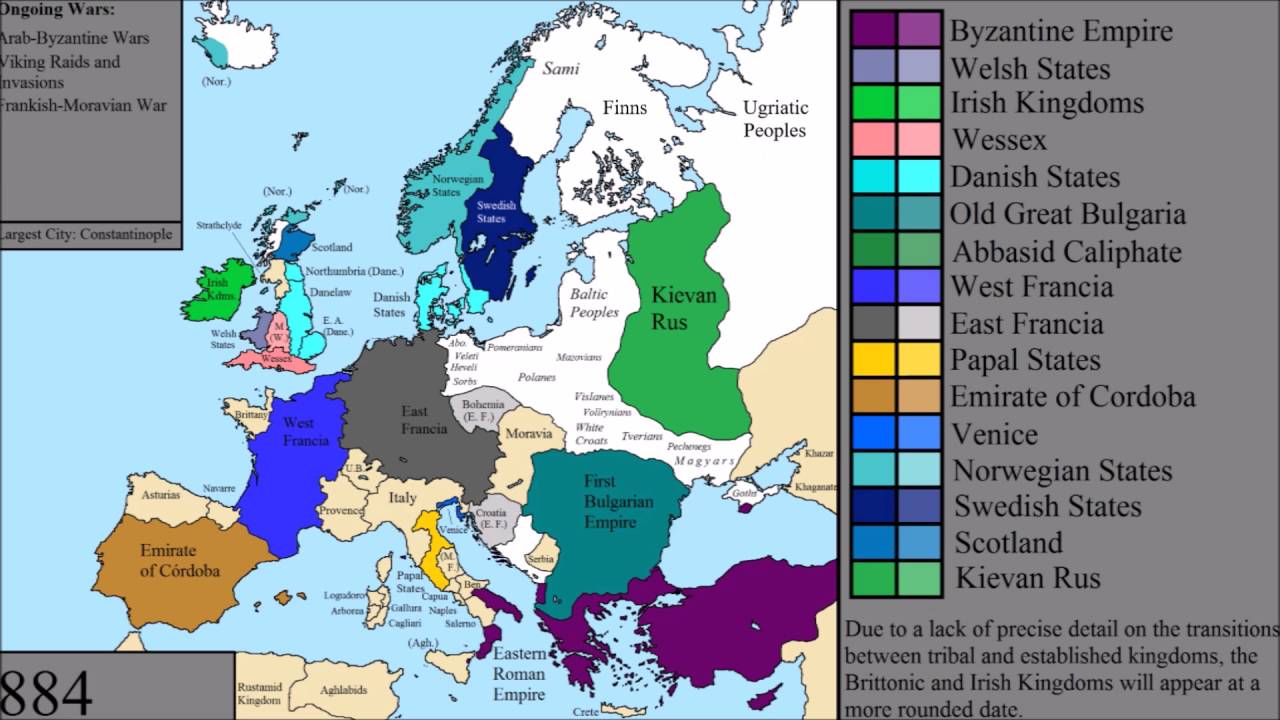

The Rise of the Nation

In eastern Europe Medieval institutions continued to flourish long after the Turks captured Byzantium in 1453. Indeed, in Russia the Middle Ages ended comparatively recently, with the emancipation of serfs in 1861. In western Europe, by contrast, the Middle Ages ended about five centuries ago.

-

Summary | The Late Middle Ages in Eastern Europe

By the late eleventh century, instability in the Muslim and Byzantine empires and the expansion of the Seljuk Turks had made pilgrimages to Palestine unsafe for Christians. When Byzantine envoys asked Pope Urban II for military aid against the Seljuks, the pope responded by calling for a Crusade. Crusades, or holy wars supported by the…

-

Russia and the West | The Late Middle Ages in Eastern Europe

A final development of these two centuries was to prove of the utmost importance for the future Russia. This was the slow and gradual penetration of foreigners and foreign ideas, a process welcomed with mixed feelings by those who prized the technical and mechanical learning they could derive from the West while fearing Western influence…

-

The Expansion of Russia, to 1682 | The Late Middle Ages in Eastern Europe

The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries saw tremendous expansion of the Russian domain. Russian pioneers, in search of furs to sell and new land to settle, led the way, and the government followed. Frontiersmen in Russia were known as Cossacks. Cossack communities gradually became more settled, and two Cossack republics, one on the Dnieper River, the…

-

The Role of the Church | The Late Middle Ages in Eastern Europe

The church remained the partner of the autocracy. The czar controlled the election of the patriarch of Moscow, a rank to which the archbishop was elevated in 1589. In the seventeenth century there were two striking instances when a patriarch actually shared power with the czar. In 1619 the father of Czar Michael Romanov, Filaret,…

-

The Role of the Zemski Sobor, 1613-1653 | The Late Middle Ages in Eastern Europe

The zemski sobor now elected as czar Michael Romanov, grand-nephew of Ivan IV. Michael succeeded with no limitations placed upon his power by the zemski sobor or by any other body; he was an elected autocrat. For the first ten years of his reign, the zemski sobor stayed in continual session. It assisted the uncertain…

-

The Time of Troubles, 1598-1613 | The Late Middle Ages in Eastern Europe

Though the territory was wide and the imperial rule absolute, ignorance, illiteracy, and inefficiency weakened Russian society. Though the old nobility had been weakened, the new gentry was not firmly in control of the machinery of government. Ivan’s son and heir, Feauedor (r. 1584-1598), was an imbecile, and with his death the Moscow dynasty, descended…

-

The Reign of Ivan the Terrible, 1533-1584 | The Late Middle Ages in Eastern Europe

Many of the disorders that characterized Russian history in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries began in the long reign of Ivan IV, the Terrible. Pathologically unbalanced, Ivan succeeded to the throne as a small child. In 1547 he threw off the tutelage of the nobles, and embarked upon a period of sound government and institutional…

-

Nobles and Serfs | The Late Middle Ages in Eastern Europe

Between the accessions of Ivan III in 1462 and Peter the Great in 1689, the autocracy overcame the opposition of the old nobility. The estates of the old nobility, which had always been hereditary, became service estates. By the end of the period the two types of nobles and the two types of estates had…

-

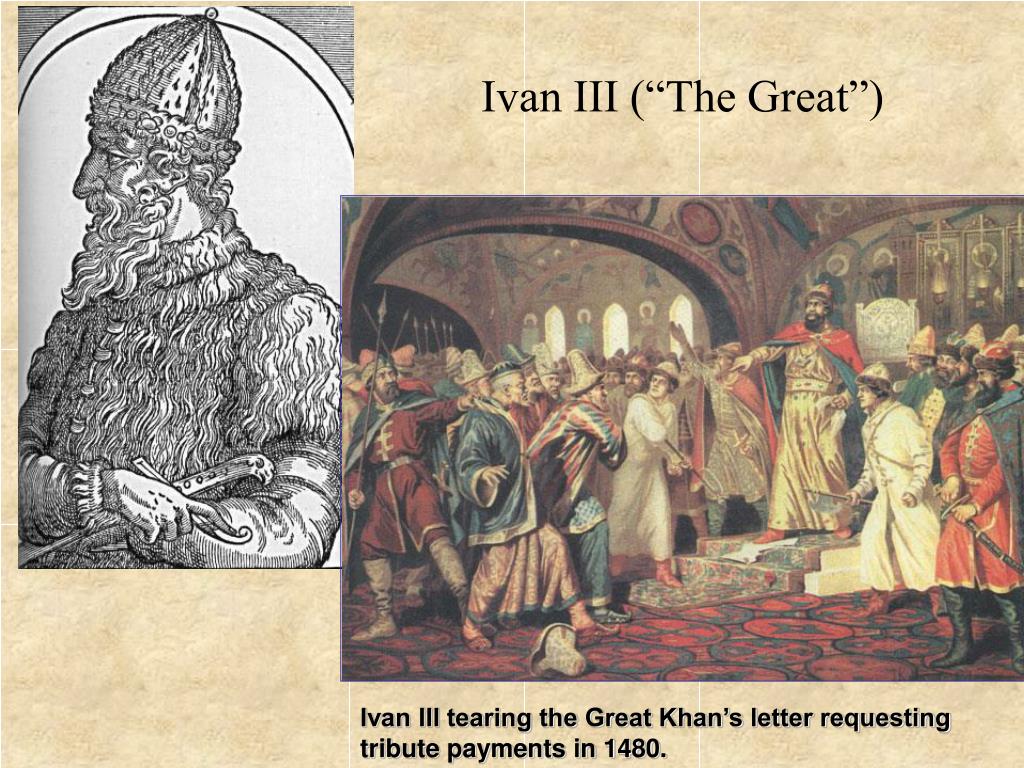

The Development of the Muscovite State | The Late Middle Ages in Eastern Europe

Moscow lay near the great watershed from which the Russian rivers flow north into the Baltic or south into the Black Sea. It was richer than the north, could provide enough food for its people, and had flourishing forest industries. Thus, when the Tatar grip relaxed and trade could begin again, Moscow was advantageously located.…

A History of Civilization