-

Western and Northern Lands, 1386-1478 | The Late Middle Ages in Eastern Europe

The collapse of Kievan Russia about the year 1200 led to the formation of a series of virtually independent petty principalities. These states were too weak and disunited to resist the constant pressure from Poland and Lithuania. By the early fourteenth century, the grand duke of Lithuania, with his capital at Vilna, ruled nominally over…

-

Russia from the Thirteenth to the End of the Seventeenth Centuries | The Late Middle Ages in Eastern Europe

Scholars refer to “the Russian question” as a means in invoking several historical concerns. What forces were at work to generate a Russian expansionism and consolidation of outlying territories? For how long would an enlarged or enlarging Russia remain stable? Would individual nationalities and languages reassert themselves despite Russian conquest?

-

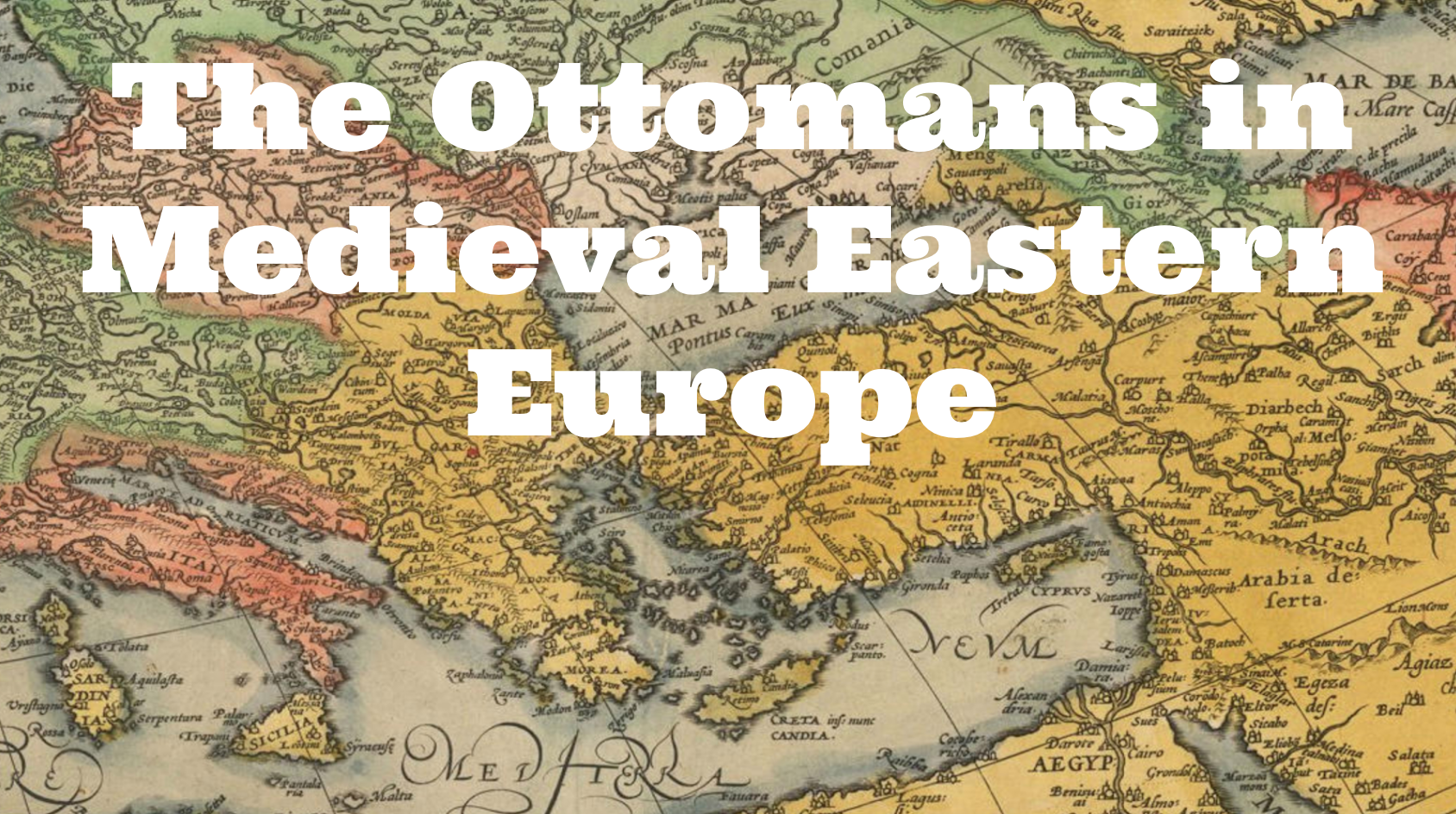

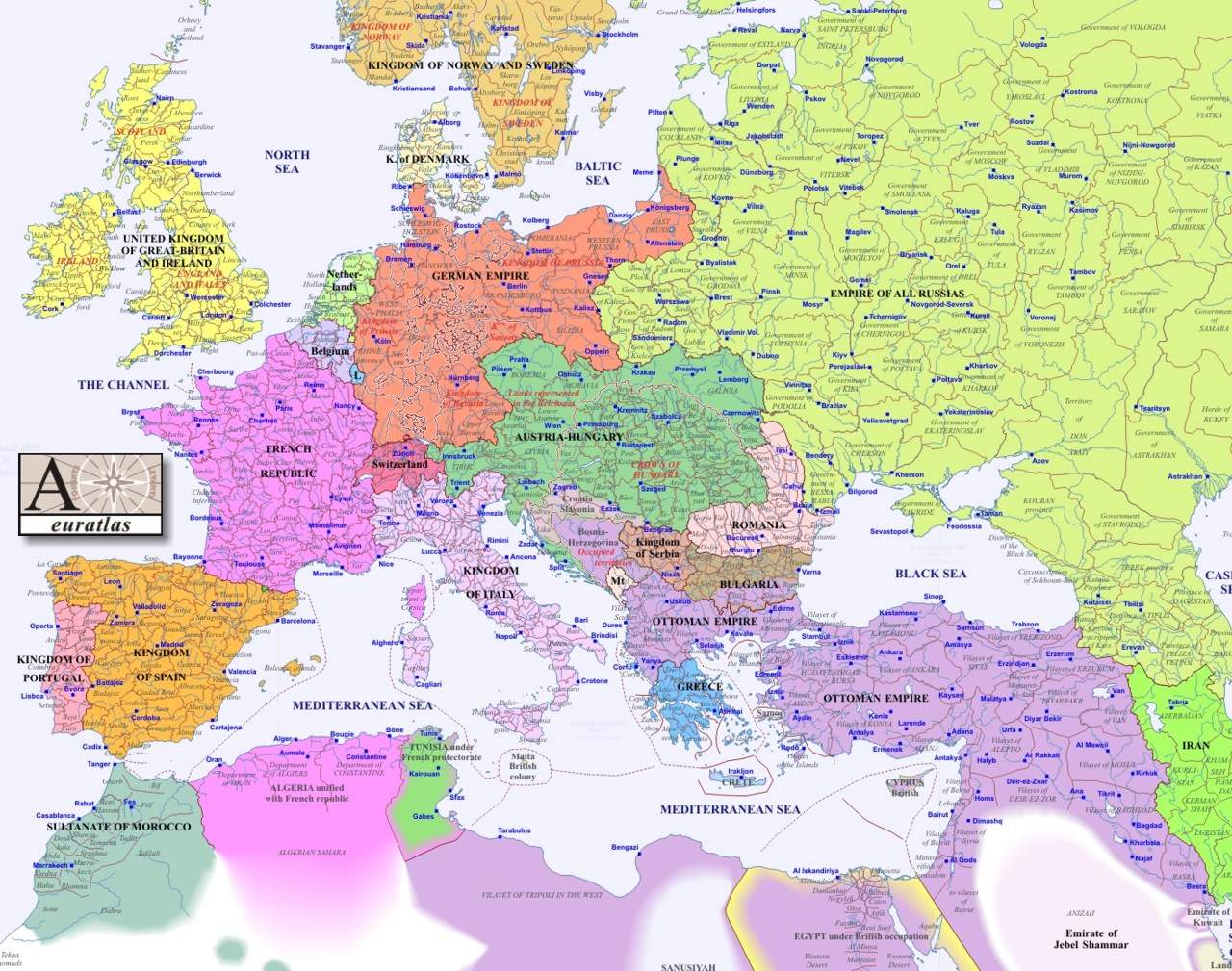

Ottoman Expansion and Retraction, to 1699 | The Late Middle Ages in Eastern Europe

By the end of the 1460s most of the Balkan peninsula was under Turkish rule. Thus the core of the new Ottoman state was Asia Minor and the Balkans. From this core, before the death of Muhammad II in 1481, the Turks expanded across the Danube into modern Romania and seized the Genoese outposts in…

-

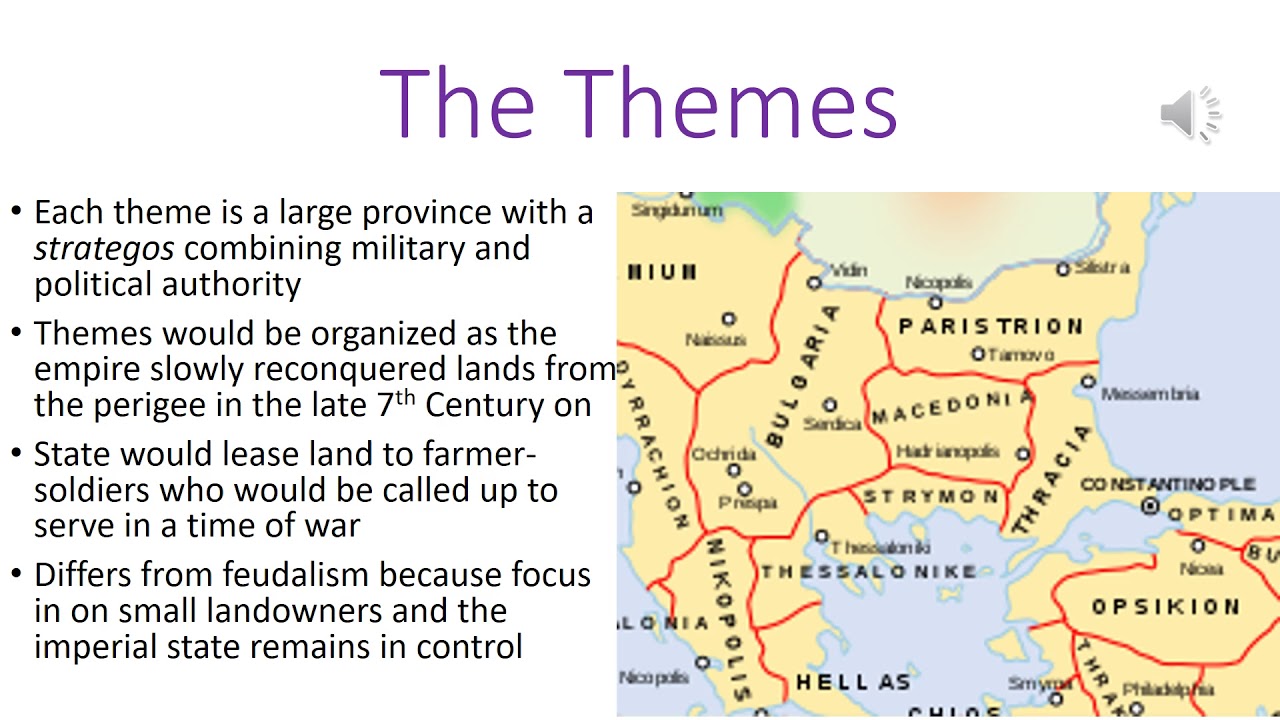

The Ottoman System | The Late Middle Ages in Eastern Europe

Until the sixteenth century, the Ottomans showed tolerance to their infidel subjects, permitting Christians and Jews to serve the state and allowing the patriarch of Constantinople and the Grand Rabbi to act as leaders of their own religious communities, or millets. The religious leader not only represented his people in their dealings with the Ottoman…

-

The Ottoman Empire, 1453-1699 | The Late Middle Ages in Eastern Europe

Part of the Ottomans’ inheritance no doubt came from their far-distant past in central Asia, when they had almost surely come under the influence of China and had lived like other nomads of the region. Their language, their capacity for war, and their rigid adherence to custom may go back to this early period.

-

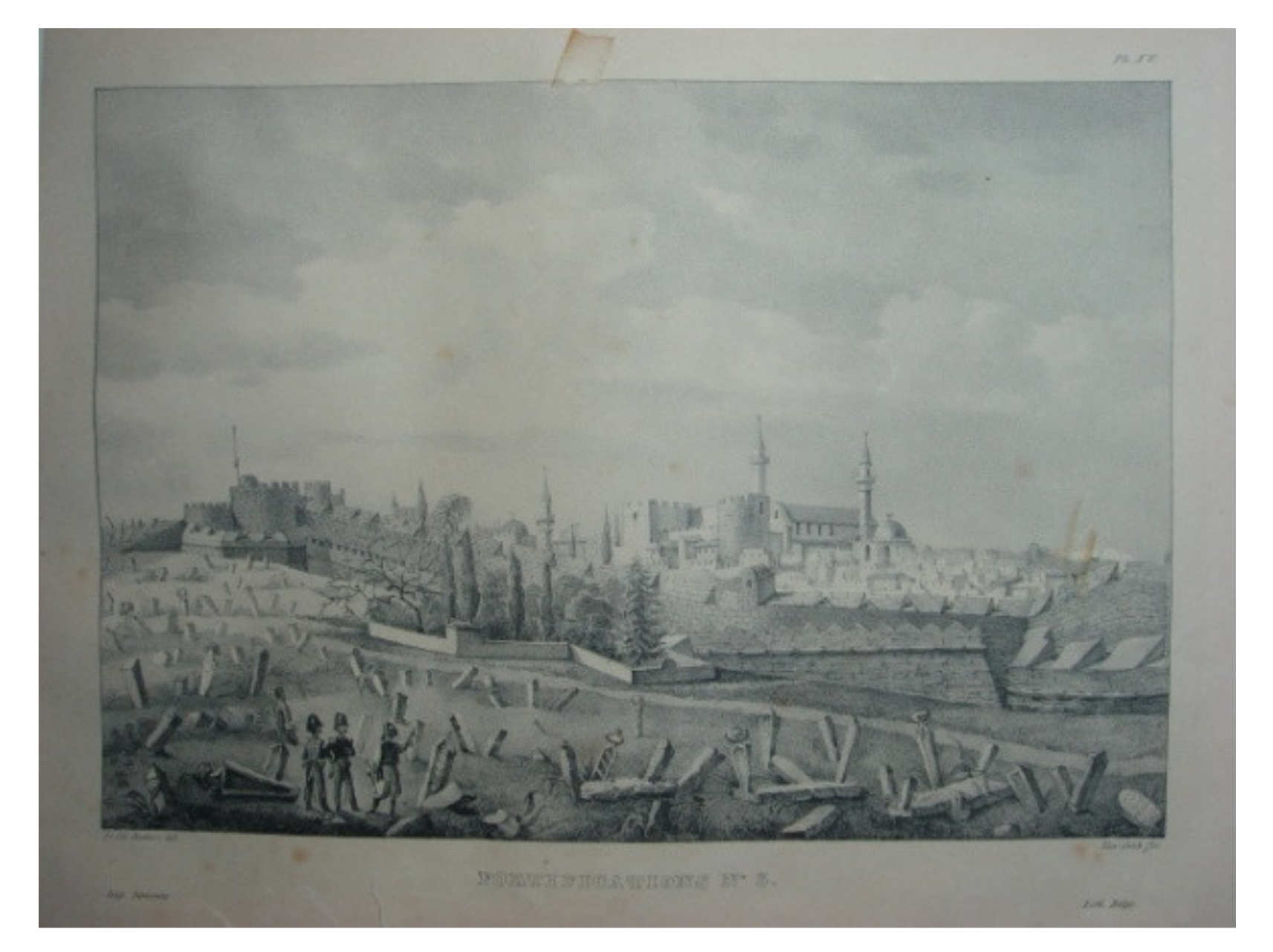

The Sack of Constantinople

A contemporary Greek historian who was an eyewitness to the sack of Constantinople in 1204 described atrocities of which he had thought human beings incapable: How shall I begin to tell of the deeds done by these wicked men? They trampled the images underfoot instead of adoring them. They threw the relics of the martyrs…

-

The Advance of the Ottoman Turks, 1354-1453 | The Late Middle Ages in Eastern Europe

By the fourteenth century the Ottoman Turks had begun to press against the borders of Byzantine Asia Minor. Economic and political unrest led the discontented population of this region to prefer the Ottomans to the harsh and ineffectual Byzantine officials. Farmers willingly paid tribute to the Turks, and as time went on many of them…

-

Pope Urban at Clermont

Pope Urban proclaimed the First Crusade with these words: The Turks, a race of Persians, who have penetrated within the boundaries of Romania even to the Mediterranean to that point which they call the Arm of Saint George, in occupying more and more of the lands of the Christians, have overcome them, have overthrown churches,…

-

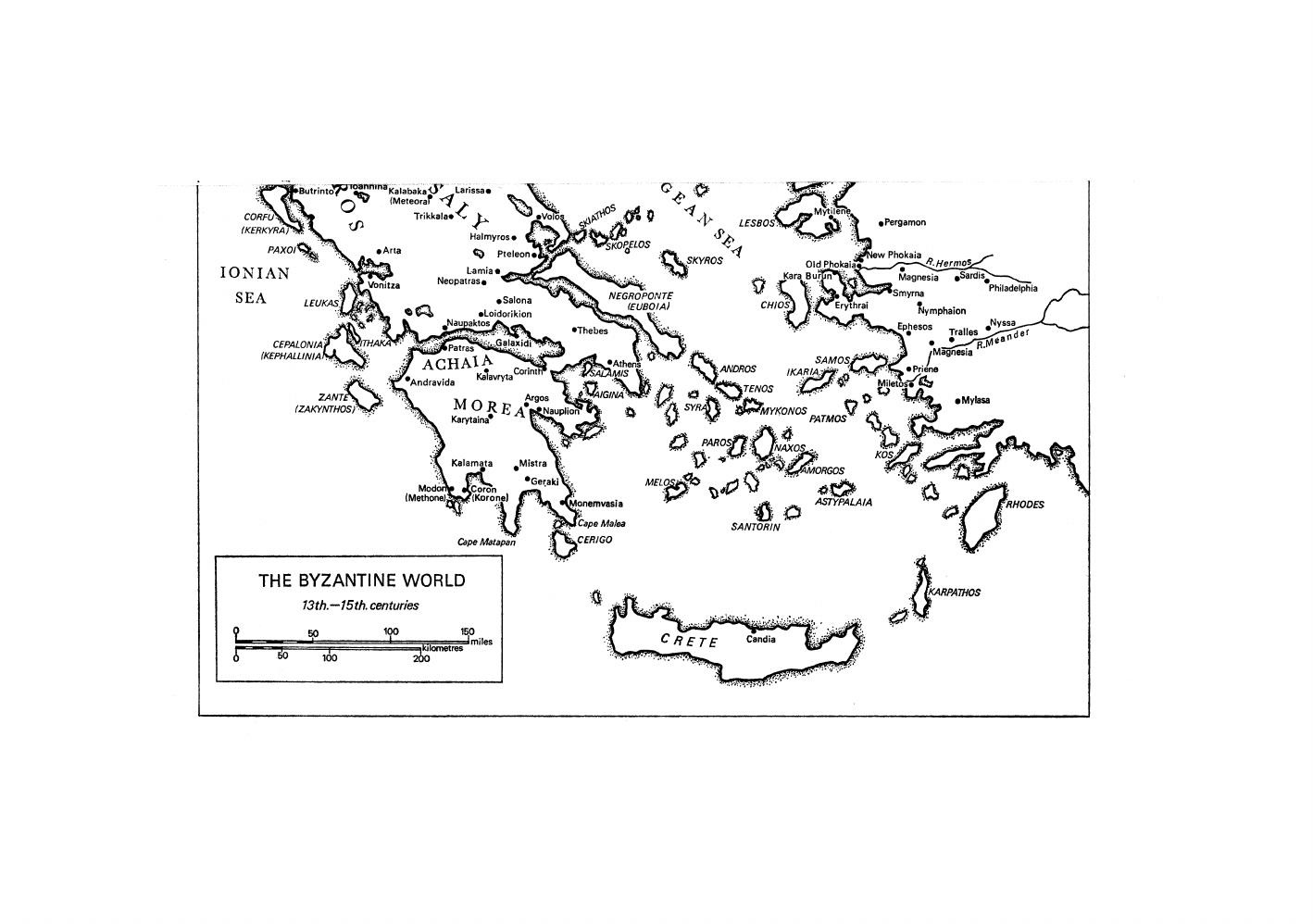

Byzantium after 1261 | The Late Middle Ages in Eastern Europe

When the Greeks of Nicaea under Michael VIII Palaeologus (r. 1259-1282) recaptured Constantinople, they found it depopulated and badly damaged and the old territory of the Empire mostly in Latin hands. It was impossible for Michael to reconquer all of Greece or the islands, to push the frontier in Asia Minor east of the Seljuk…

-

The Latin Empire, 1204-1261 | The Late Middle Ages in Eastern Europe

After the sack of Constantinople, the Latins elected Baldwin of Flanders as the first Latin emperor (12041205), and the title continued in his family during the fifty-seven years of Latin occupation. The Venetians chose the first Latin patriarch and kept a monopoly on that rich office. The territories of the Empire were divided on paper,…

-

Byzantine Decline, 1081-1204 | The Late Middle Ages in Eastern Europe

The drama of Byzantium’s last centuries was played out to the accompaniment of internal decay. Alexius I Comnenus had captured the throne in 1081. Thereafter the imperial accumulation of land seems to have gone unchecked.

-

The Fall of Byzantium, 1081-1453 | The Late Middle Ages in Eastern Europe

During its last 372 years, the fate of the Byzantine Empire increasingly depended upon western Europe. The flood of crusaders first made the Byzantines uneasy and ultimately destroyed them. From 1204 to 1261, while the Byzantine government was in exile from its own capital, its chief aim was to drive out the hated Latins. But…

-

The Impact of the Crusades on the West | The Late Middle Ages in Eastern Europe

The number of crusaders and pilgrims who went to the East and returned home was large. From Marseilles alone the ships of the Hospitalers and the Templars carried six thousand pilgrims a year. Ideas flowed back and forth with the people.

-

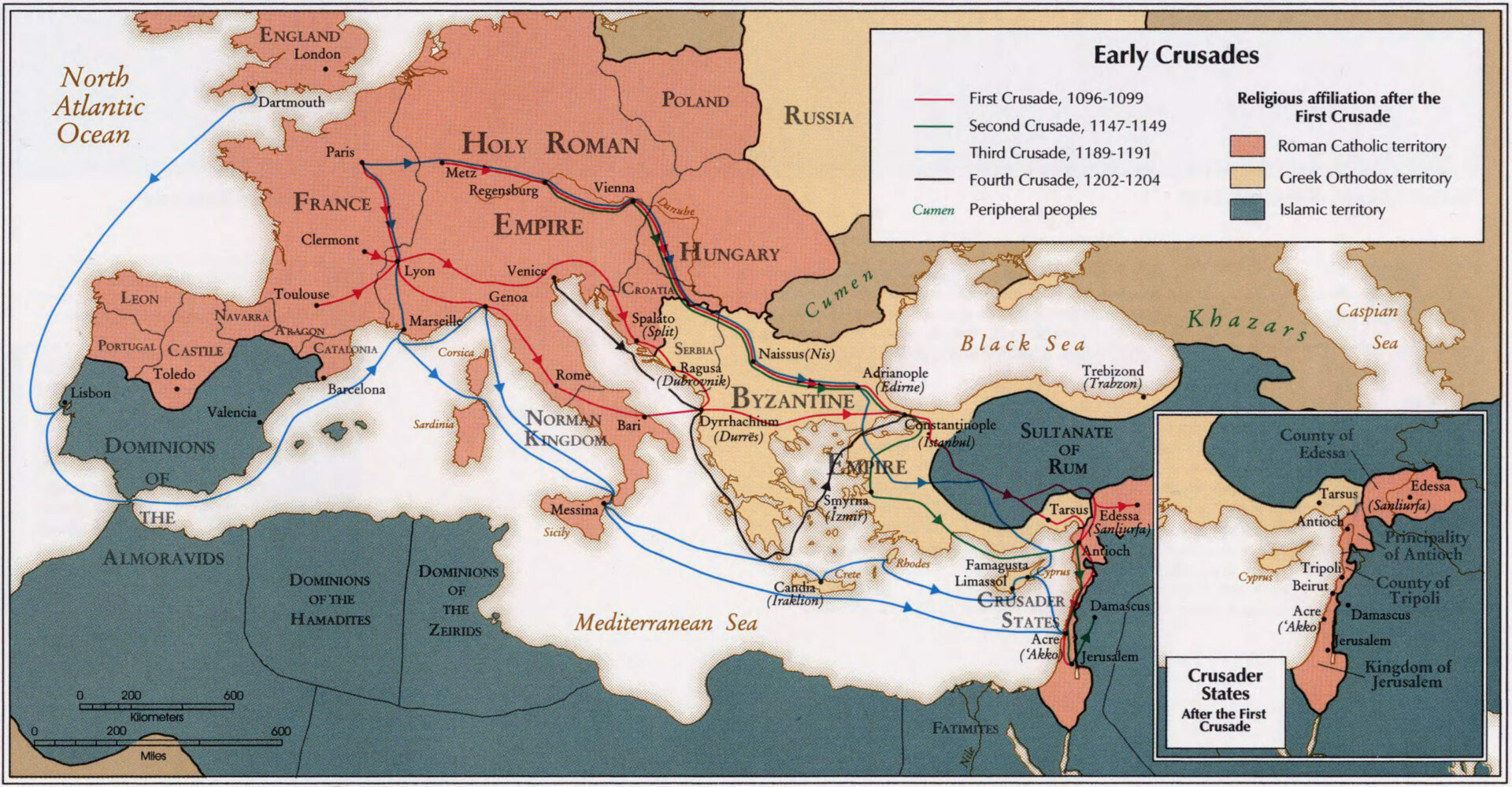

The Muslim Reconquest and the Later Crusades, 1144-1291 | The Late Middle Ages in Eastern Europe

It is a wonder that the crusader states lasted so long. It was not the castles or the military orders that preserved them so much as the disunion of their Muslim enemies. When the Muslims did achieve unity under a single powerful leader, the Christians suffered grave losses. Beginning in the late 1120s, Zangi, governor…

-

The Military Orders, 1119-1798 | The Late Middle Ages in Eastern Europe

Early in their occupation of the eastern Mediterranean, the Westerners founded the military orders of knighthood. The first of these were the Templars, started about 1119 by a Burgundian knight who sympathized with the hardships of the Christian pilgrims. These knights took vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience, and were given headquarters near the ruins…

-

The Crusader States, 1098-1109 | The Late Middle Ages in Eastern Europe

Meanwhile, the main body of the army was besieging the great fortress city of Antioch, which finally was conquered by treachery after more than seven months. Antioch became the center of the second crusader state under the Norman Bohemond. The other crusaders then took Jerusalem by assault in July 1099. Godfrey of Bouillon was chosen…

-

The First Crusade, 1095 | The Late Middle Ages in Eastern Europe

Pope Urban II (r. 1088-1099) carried on the tradition of Gregory VII. To his Council of Piacenza in 1095 came envoys from Alexius, who asked for military help against the Turks. The Byzantine envoys also seem to have stressed the sufferings of the Christians in the East. Eight months later, at the Council of Clermont,…

-

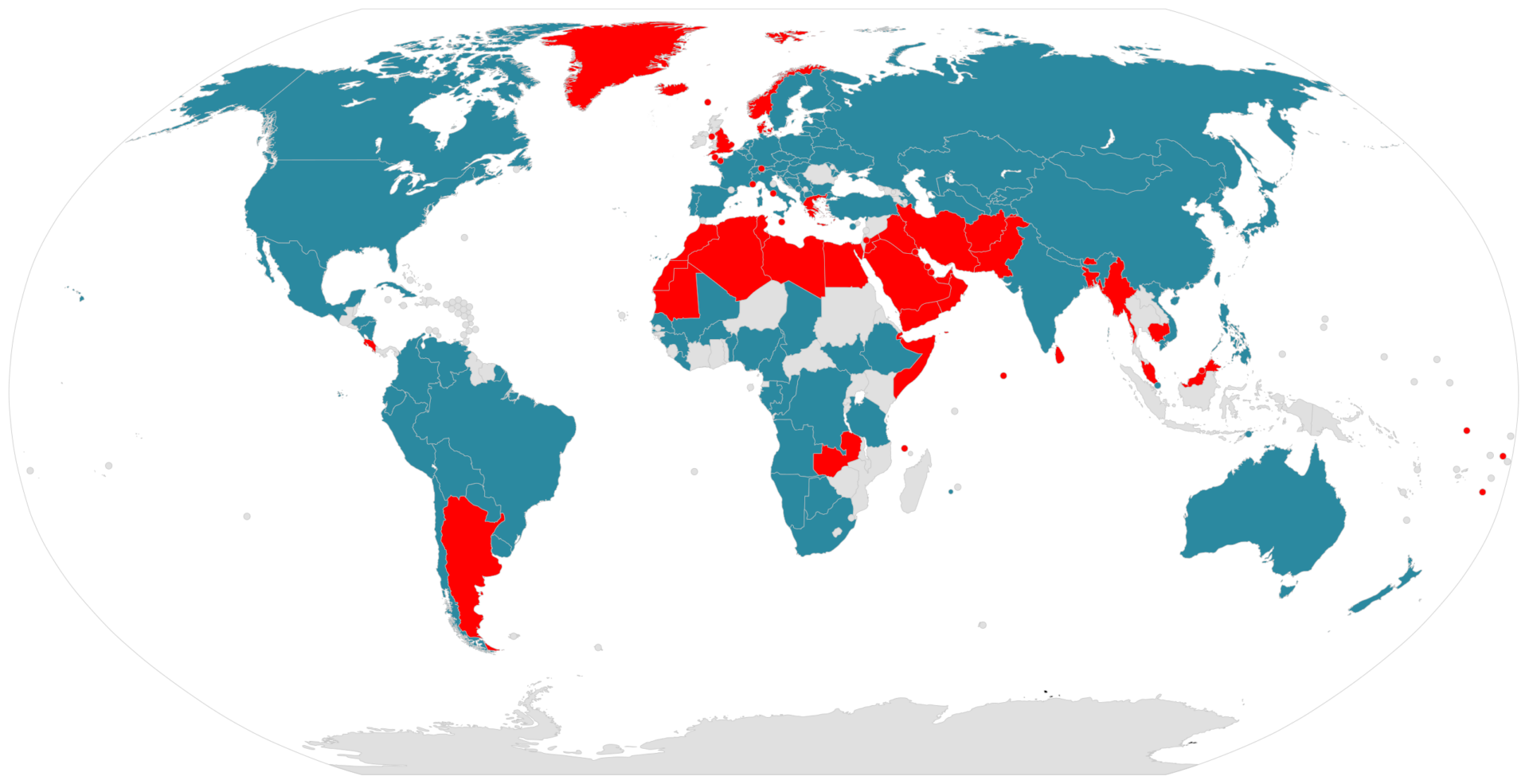

The Crusades

The term crusade is used to sanctify a wide variety of single-minded efforts to bring about change. At times the term refers to attempts, as with the Crusades described here, to take back lost lands and reabsorb them into some dominant culture, or to impose the will of one group upon another. While the original…

-

Origins of the Crusades | The Late Middle Ages in Eastern Europe

From the third century on, Christians had visited the scenes of Christ’s life. Before the Muslim conquest in the seventh century, pilgrims came from Byzantium and the West, often seeking sacred relics for their churches at home. For a while after the Muslim conquest, pilgrimages were very dangerous and could be undertaken only by the…

-

The Late Middle Ages in Eastern Europe

In Spain the fighting of Christian against Muslim had been virtually continuous since the Muslim conquest in the eighth century. Just after the year 1000 the Cordovan caliphate weakened, and the Spanish Christian princes of the north won the support of the powerful French abbey at Cluny. Under prodding from Cluny, French nobles joined the…

-

Summary | The Beginnings of the Secular State

Between 987 and 1314 the French monarchy grew in power and prestige until it dominated the machinery of government. France became the first large, unified state in the medieval West.

-

Literature in the West | The Beginnings of the Secular State

In literature, as in science and in social and economic life, Latin continued to be the language of the church and of learned communication everywhere in western Europe. All the churchmen—John of Salisbury, Abelard, Bernard, Aquinas, and the rest—wrote Latin even when corresponding informally with their friends. Children began their schooling by learning it. It…

-

The Song of Roland

Roland has died on the field of battle, and Charlemagne believes that he was betrayed by Ganelon, who with his men deserted the field at a crucial moment. Ganelon is found guilty by trial, but before he can be executed one of his followers, Pinabel, challenges one of the emperor’s most devoted liege men to…

-

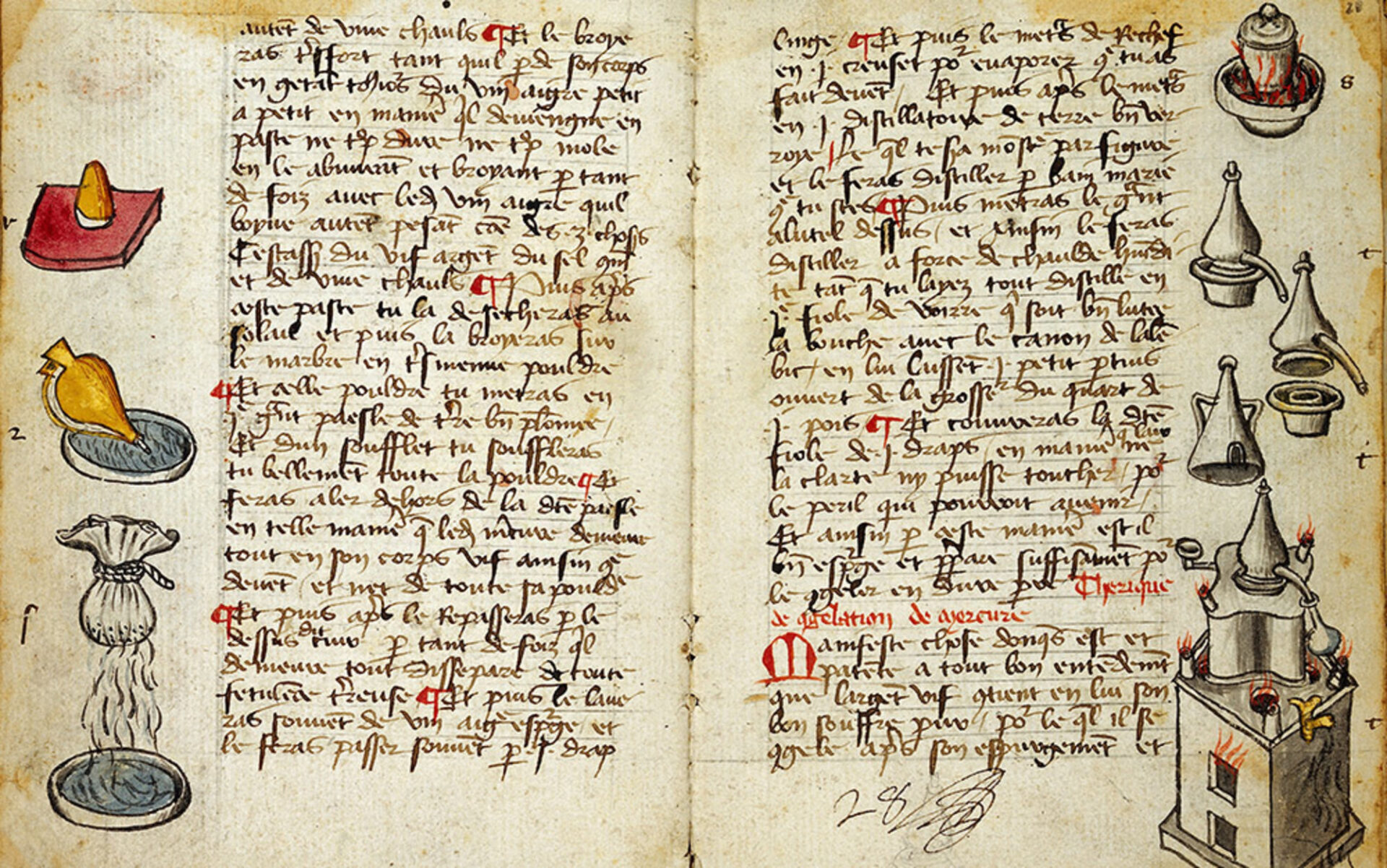

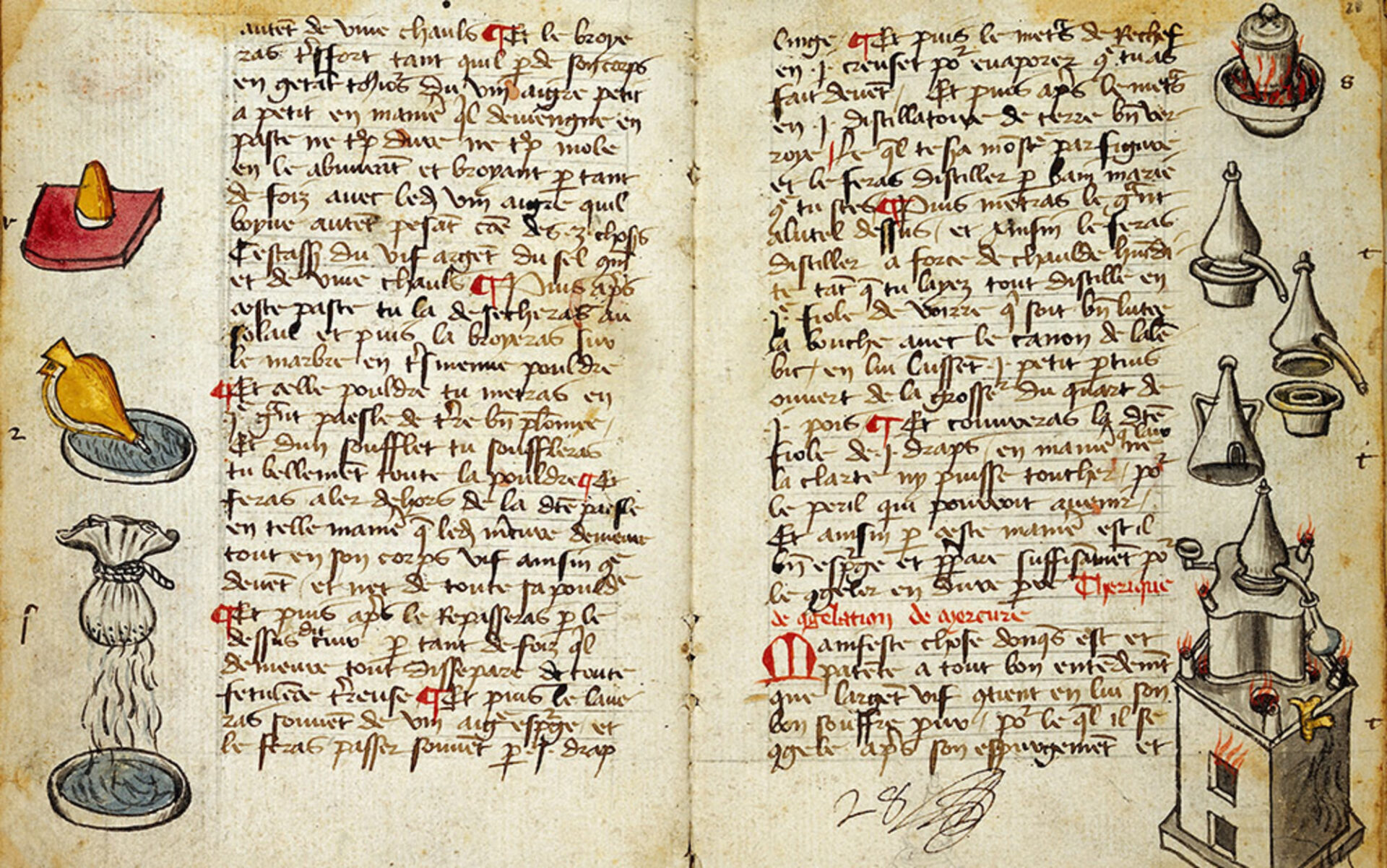

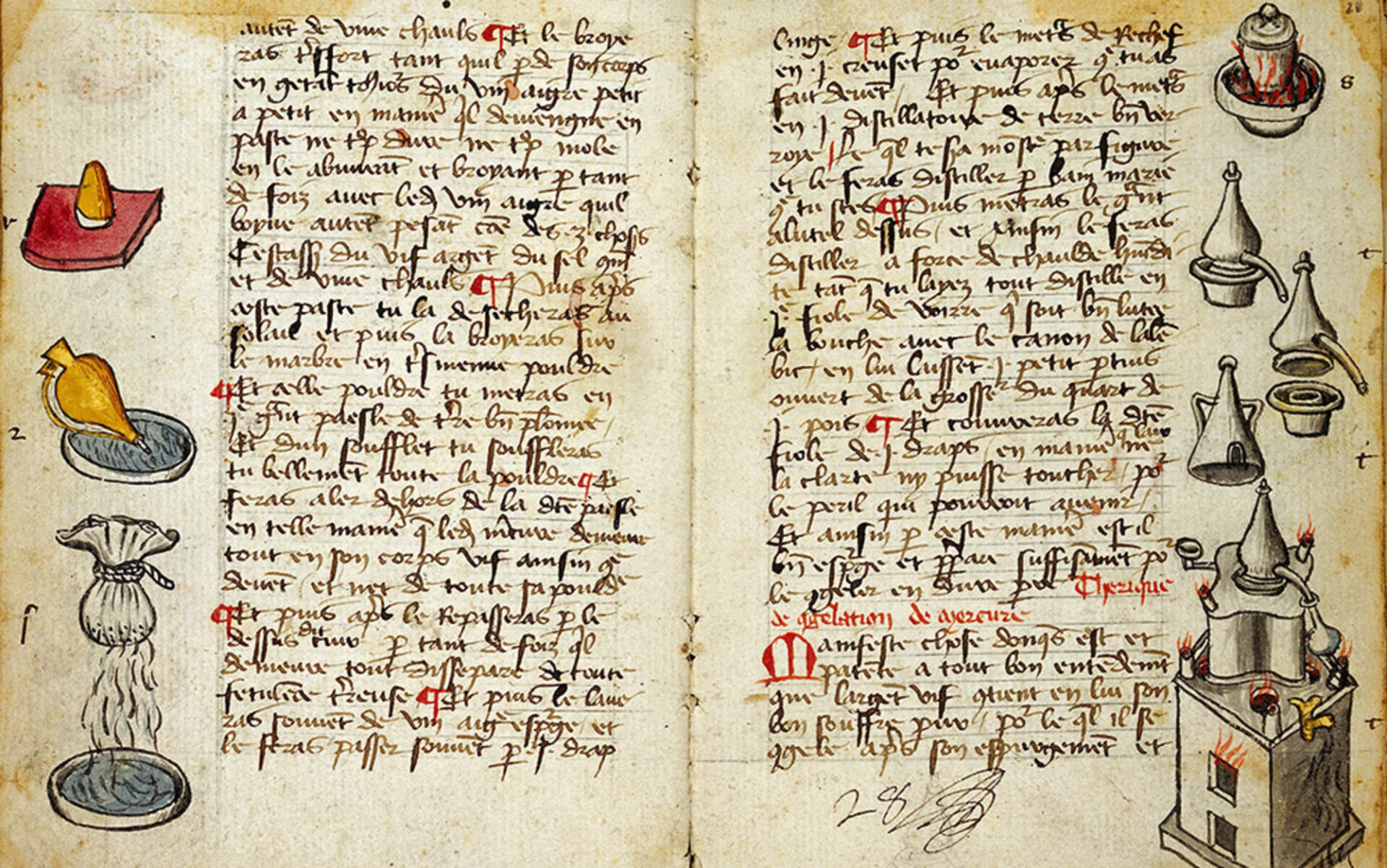

Science in the West | The Beginnings of the Secular State

The Middle Ages saw considerable achievement in natural science. Modern scholars have revised downward the reputation of the Oxford Franciscan Roger Bacon (c. 1214-1294) as a lone, heroic devotee of “true” experimental methods; but they have revised upward such reputations as those of Adelard of Bath (twelfth century), who was a pioneer in the study…

-

Science and Literature in the West | The Beginnings of the Secular State

There was throughout the West a growing interest in scientific inquiry that served to unite peoples. Science had always been international, since ideas cannot be restrained within the borders of a state, but technology—that is, the application of science to practical ends—may for a time be held within the confines of a single nation through…

-

Edward I, 1272-1307 | The Beginnings of the Secular State

By the late thirteenth century the earlier medieval belief that law is custom and that it cannot be made was fading, and Edward I enacted a great series of systematizing statutes. Edward’s statutes were framed by the experts of the small council, who elaborated and expanded the machinery of government. Each of the statutes was…

-

The Origins of Parliament, 1258-1265 | The Beginnings of the Secular State

It is to these years under Henry III that historians turn for the earliest signs of the major contribution of the English Middle Ages to the West—the development of Parliament. The word parliament comes from French and simply means a “talk” or “parley”—a conference of any kind. The word was applied in France to that…

-

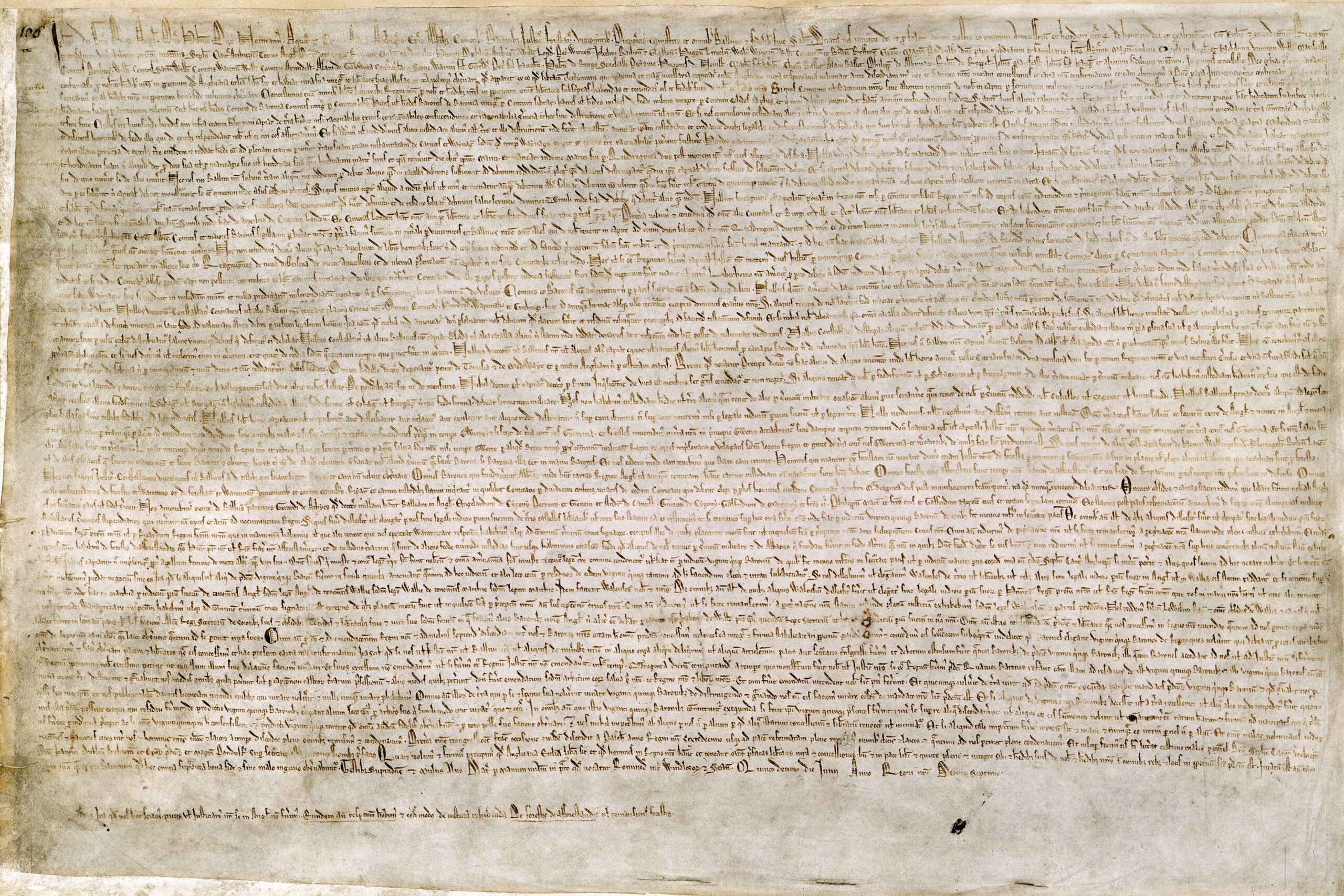

Magna Carta

The Magna Carta reaffirmed traditional rights and personal liberties against royal authority. Many of its provisions became the basis for specific civil rights enjoyed in Western democracies today. Following are a few excerpts from that document.

-

Magna Carta, 1215 | The Beginnings of the Secular State

A quarrel with perhaps a third of the English barons arose from John’s ruthlessness in raising money for the campaign in France and from his practice of punishing vassals without trial. The barons hostile to John renounced their homage to him and drew up a list of demands, most of which they forced him to…

-

Richard I and John, 1189-1216 | The Beginnings of the Secular State

Henry Ifs son, Richard the Lionhearted (r. 1189-1199), spent less than six months of his ten-year reign in England, but thanks to Henry II, the bureaucracy functioned without the presence of the king. Indeed, it functioned all too well for the liking of the population, since Richard needed more money than had ever been needed…

-

Henry I and Henry II, 1100-1189 | The Beginnings of the Secular State

William’s immediate successors extended his system. They made their administrators depend on the king alone by paying them fixed salaries. Household and curia regis grew in size, and special functions began to develop. Within the curia regis the king’s immediate advisers became a “small council” and the full body met less often. The royal chancery…

-

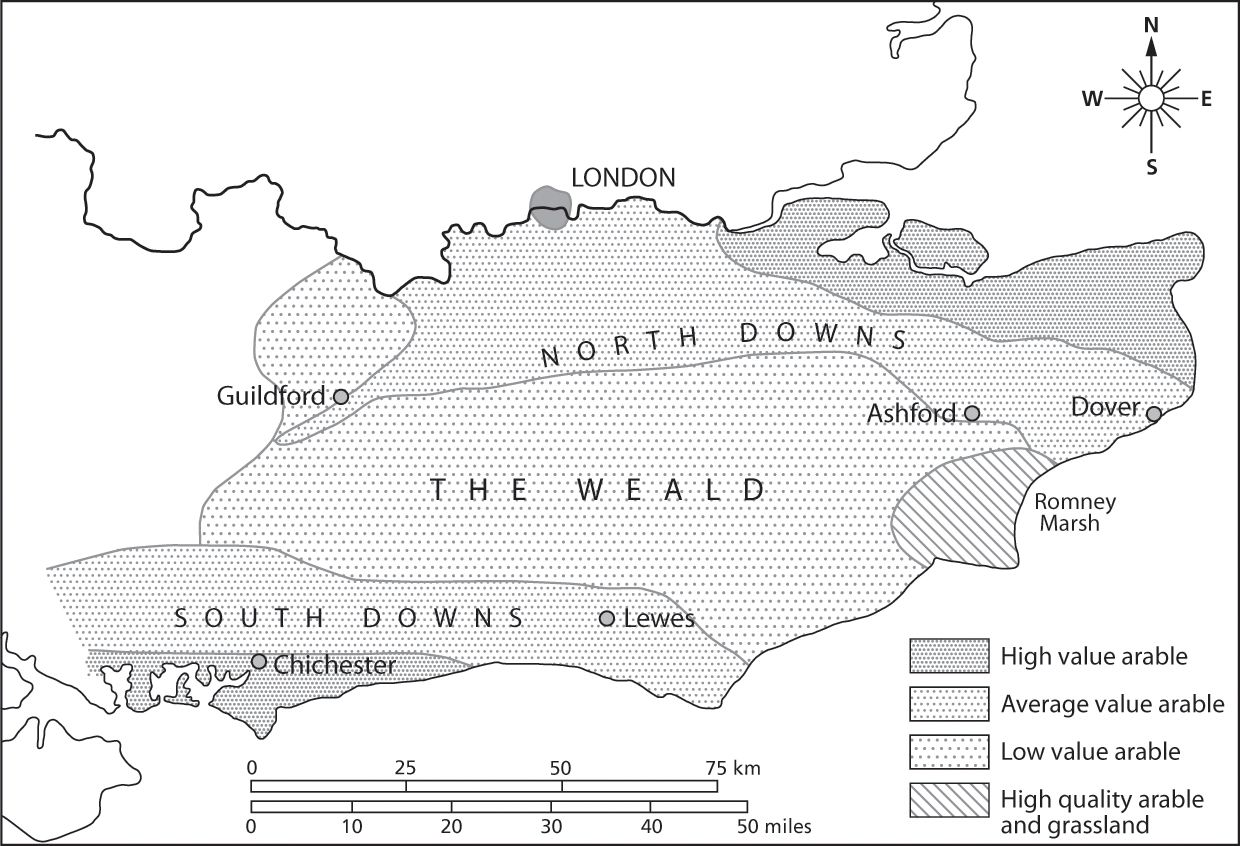

The Norman Conquest, 1066 | The Beginnings of the Secular State

William successfully asserted his rights over the vigorous and tough Norman nobility. He allowed no castle to be built without his license, and insisted that, once built, each castle be put at his disposal on demand. The Norman cavalry was formidable and early perfected the technique of charging with the lance held couched, so that…

-

The Development of England | The Beginnings of the Secular State

England became a major power as the result of the Norman Conquest of 1066. In that year William, duke of Normandy (c. 1027-1087), defeated the Anglo-Saxon forces at Hastings on the south coast of England. The Anglo-Saxon monarchy had, since the death of Canute in 1035, fallen prey to factions. Upon the death of Edward…

-

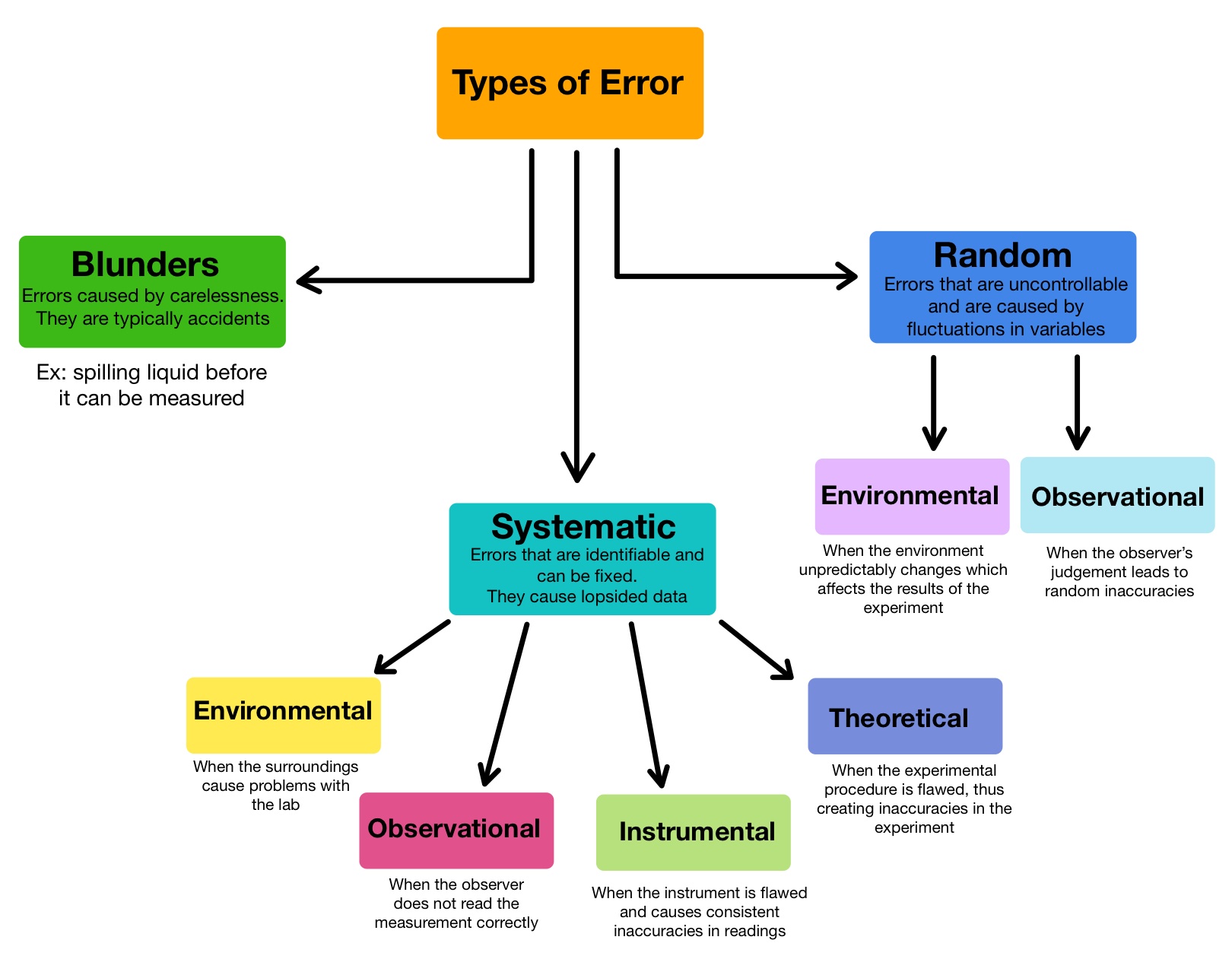

Sources of Error

The great Arab philosopher of history Ibn Khaldun (1332-1406) was the first to work out a substantial methodology for historical knowledge. In the Prolegomena to his work he analyzed the “sources of error in historical writing”:

-

Philip the Fair, 1285-1314 | The Beginnings of the Secular State

After the death of St. Louis, the French monarchy experienced a trend toward centralization and consolidation of administrative functions. This tendency began with the reign of St. Louis’s grandson, Philip IV (r. 1285-1314). Called “the Fair,” Philip ruthlessly pushed the royal power; the towns, the nobles, and the church suffered further invasions of their rights…

-

St. Louis, 1226-1270 | The Beginnings of the Secular State

Further advances in royal power came with Louis IX. Deeply pious, Louis carried his high standards over into his role as king. He wore simple clothes, gave alms to beggars, washed the feet of lepers, built hospitals, and created in Paris the Sainte-Chapelle (Holy Chapel) to hold a reliquary containing Christ’s Crown of Thorns. The…

-

Royal Administration | The Beginnings of the Secular State

Administrative advances kept pace with territorial gains. Philip Augustus systematically collected detailed information on precisely what was owed to him from the different royal fiefs. He increased the number of his own vassals, and exacted stringent guarantees—such as a promise that if a vassal did not perform his duties within a month, he would surrender…

-

The Winning of the South | The Beginnings of the Secular State

The Capetians next moved to take over the rich Mediterranean south. Its people belonged to the heretical church of the Cathars, with its center at the town of Albi. Hence, they were called Albigensians. They believed that the history of the universe was one long struggle between the forces of light (good) and the forces…

-

The Capetians, 987-1226 | The Beginnings of the Secular State

When Hugh Capet (c. 938-996) came to the throne of France in 987, he was the first of a male line that was to continue uninterrupted for almost 350 years. Like the Byzantine emperors, but with better luck, the Capetians had procured the election and coronation of the king’s eldest son during his father’s lifetime.…

-

The Development of France: From Hugh Capet to Philip the Fair | The Beginnings of the Secular State

Between 987 and 1314 the French monarchy grew in power and prestige until it dominated the machinery of government. France became the first large and unified state in the medieval West, a state built largely by the monarchy.

-

The Beginnings of the Secular State

In those lands that became France and England, a series of strong monarchs emerged to provide the state with a center of authority that could contest with the church for the loyalties of the people. While open conflict with the papacy was not yet contemplated, and no state in western Europe was secular in the…

-

Summary | Church and Society in the Medieval West

Medieval Europe was in its most distinctive phase as a distinctively Western civilization, with many shared values that gave it some temporary intellectual unity and separated it from other civilizations. The European economy and population began to expand in the eleventh century. New technology such as the windmill and the heavy plow led to increased…

-

The Church and The Arts | Church and Society in the Medieval West

The Romanesque style dominated church building in the eleventh and most of the twelfth centuries. The Gothic style, following it and developing from it, began in the late twelfth century and prevailed down to the fifteenth. Among the great Romanesque churches were those built at Mainz, Worms, and Speyer in western Germany.

-

Knowledge that is Lost

Societies once possessed knowledge that was later lost: Greek science, Muslim scholarship, the wheel and the cart that disappeared from the region of their invention, the Middle East. Thus phases do not always represent a steady progression from a lower to a higher complexity, for complex knowledge and practice can be forgotten. This awareness may…

-

The Church and Mysticism | Church and Society in the Medieval West

There were many mystics in the Middle Ages. Bernard, mystic and activist, denounced Abelard, thinker and rationalist teacher. St. Francis also distrusted formal intellectual activity. For him, Christ was no philosopher; Christ’s way was the way of submission, of subduing the mind as well as the flesh. The quality of Francis’s piety comes out in…

-

The Church and Political Thought | Church and Society in the Medieval West

In dealing with problems of human relations, medieval thinkers came fairly close to modern democratic thinking. Except for extreme realism, medieval political thought was emphatically not autocratic. To the medieval thinker the perfection of the kingdom of heaven could not possibly exist on earth, where compromise and imperfection were inescapable.

-

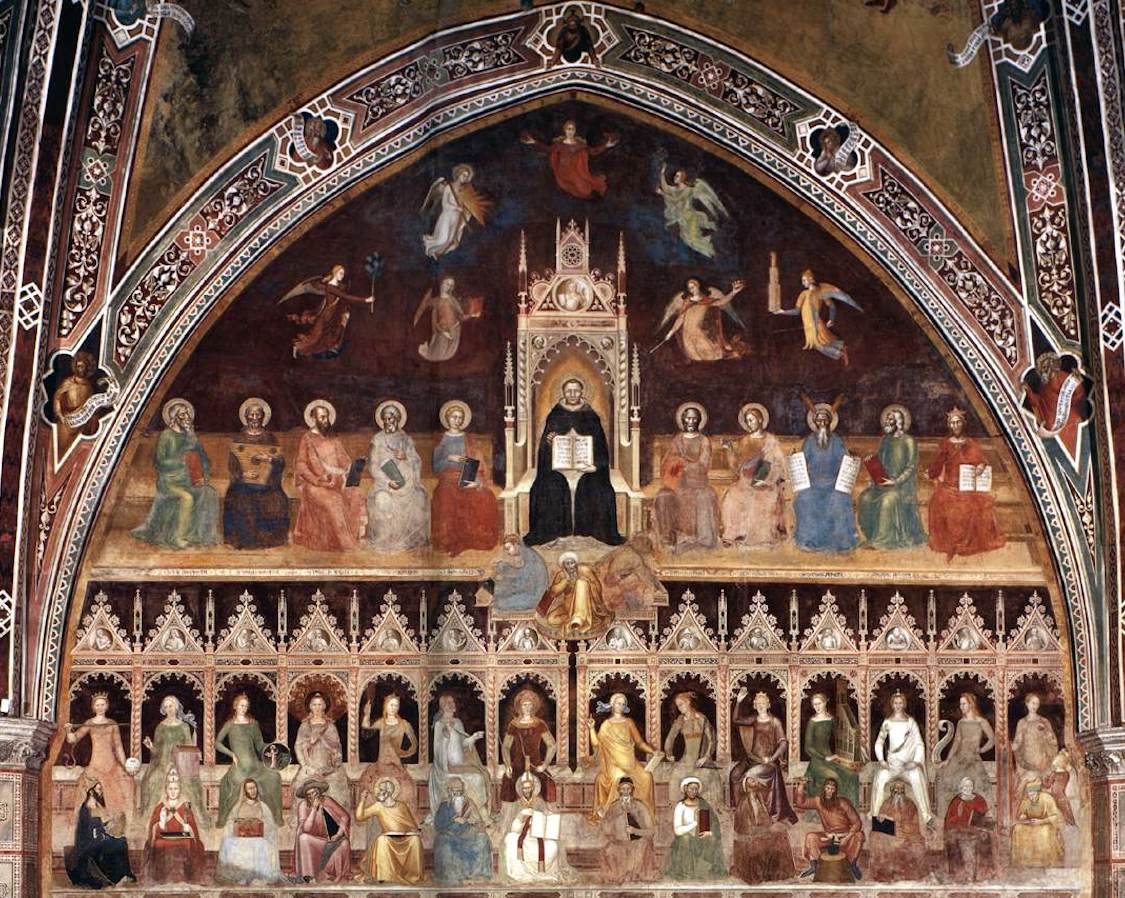

Thomas Aquinas | Church and Society in the Medieval West

By the time of Abelard’s death, the Greek scientific writings of antiquity were starting to be recovered, often through translations from Arabic into Latin. In the second half of the century came the recovery of Aristotle’s lost treatises on logic, which dealt with such subjects as how to build a syllogism (an expression of deductive…

-

The Question of Universals | Church and Society in the Medieval West

Much of the study at that time consisted of mere memorizing by rote, since in the days before printing ready reference works were scarce. Though the formal rules of scholarly debate were fixed, there was, nonetheless, lively discussion. Discussion and teaching were particularly preoccupied with defining systems by which people could live faithfully within the…

-

Education and The Church| Church and Society in the Medieval West

The church alone directed and conducted education in medieval Europe. Unless destined for the priesthood, young men of the upper classes had little formal schooling, though the family chaplain often taught them to read and write. Young women usually had less education. But the monastic schools educated future monks and priests, and the Cluniac reform,…

-

Friars: Dominicans and Franciscans | Church and Society in the Medieval West

In the early thirteenth century, the reforming movement within the church took on new aspects. As town populations grew, the new urban masses were sometimes subject to waves of mass and unthinking emotional enthusiasms which could lead to heresy. These outbreaks and the fears that led to them were a cry for spiritual help. The…

-

Augustinians and Cistercians | Church and Society in the Medieval West

One newly founded order broke with the rule of Benedict, finding its inspiration in a letter of Augustine is that prescribed simply that monks share all their property, pray together at regular intervals, dress alike, and obey a superior. Some of the “Augustinians,” as they called themselves, interpreted these general rules severely, living in silence,…

-

The Church in Society | Church and Society in the Medieval West

Frederick II was right in believing that the church needed reform. For example, Innocent IV, in fighting Frederick, had approved the appointment to a bishopric in German territory of an illiterate and dissolute young man of nineteen just because he was a member of a powerful anti- Hohenstaufen noble family; this bishop was forced to…

-

Frederick II, 1212-1250 | Church and Society in the Medieval West

Frederick II is perhaps the most interesting medieval monarch. Intelligent and cultivated, he took a deep interest in scientific experiment, wrote poetry in Italian, wrote on the sport of falconry, and was a superb politician. He was cynical, tough, a sound diplomat, an able administrator, and a statesman. Furthermore, he felt at home in Sicily—the…

-

Innocent III, 1198-1216 | Church and Society in the Medieval West

Three months after the death of Henry VI, when his son and heir, Frederick II, was only four years old, there came to the papal throne Innocent III (r. 1198-1216), the greatest of all the medieval popes. Innocent played a major part in the politics of France, England, and the Byzantine Empire. He said that…

-

Frederick Barbarossa and Henry VI, 1152-1192 | Church and Society in the Medieval West

In 1156 Frederick married the heiress to Burgundy, which had slipped out of imperial control during the Investiture Controversy. He made Switzerland the strategic center of his policy, for it controlled the Alpine passes into Italy. In Swabia he tried to build a compact, well-run royal domain, but he needed the loyalty of cooperative great…

-

Papacy and Empire, 1152-1273 | Church and Society in the Medieval West

With the revival of the study of Roman law during the twelfth century went a corresponding interest among churchmen in the systematization of canonical law. As the texts of Justinian’s civil law became familiar to the students in the law schools—of which Bologna in Italy was the most important—the Bolognese monk Gratian about 1140 published…

-

The Investiture Controversy, 1046-1122 | Church and Society in the Medieval West

The struggle originated in 1046, when the emperor Henry III found three rival popes simultaneously in office while mobs of their supporters rioted in the streets of Rome. He deposed all three. After two successive German appointees had died—perhaps by poison—Henry named a third German, Bishop Bruno of Toul, who became pope as Leo IX…

-

The Empire, 962-1075 | Church and Society in the Medieval West

When King Otto took the title of emperor in 962, he created for his successors a set of problems that far transcended the local problems of Germany. In the Carolingian West, emperor had come to mean a ruler who controlled two or more kingdoms but who did not necessarily claim supremacy over the whole world,…

-

Saxon Administration and the German Church, 911-955 | Church and Society in the Medieval West

Conrad’s successor, the duke of Saxony, became King Henry I (r. 919-936). He and his descendants, notably Otto the Great (r. 936-973) and Otto III (r. 983-1002)— successfully combated the ducal tendency to dominate the counts and to control the church. In 939 the Crown obtained the duchy of Franconia; thenceforth, the German kings, no…

-

The Investiture Controversy | Church and Society in the Medieval West

As the Carolingian Empire gradually disintegrated in the late ninth and early tenth centuries, four duchies— Franconia, Saxony (of which Thuringia was a part), Swabia, and Bavaria—arose in the eastern Frankish lands of Germany. They were military units organized by the local Carolingians, who took the title of Duke (army commander).

A History of Civilization