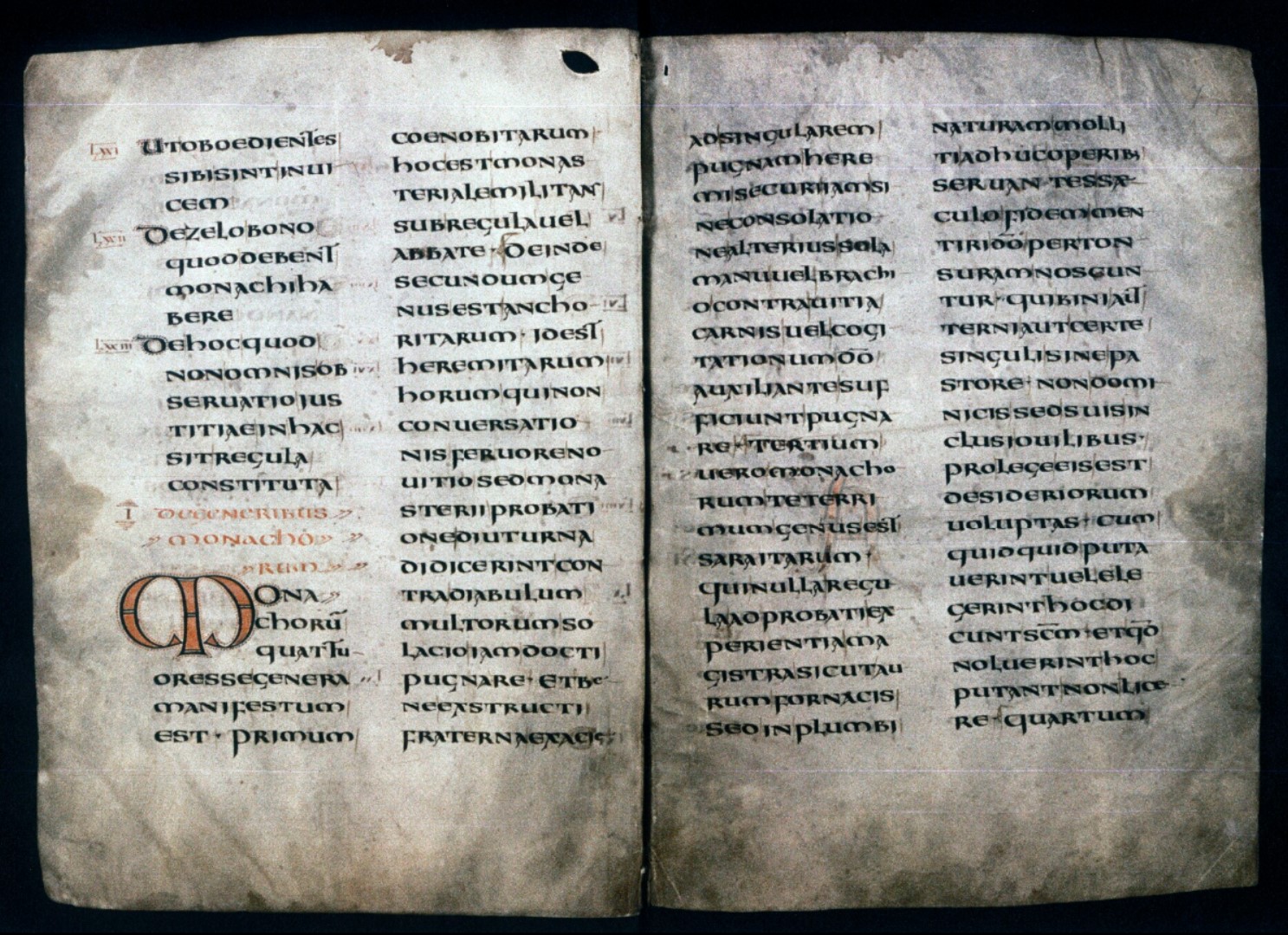

The Benedictine rule blended Roman law with the new Christian view to produce the most enduring form of monasticism in Western society. Consider the concepts of authority, rule, and equality contained in the following portions of the rule of St. Benedict:

An abbot who is worthy to preside over a monastery ought always to remember what he is called, and carry out with his deeds the name of a Superior. For he is believed to be Christ’s representative, since he is called by His name, the apostle saying, “Ye have received the spirit of adoption of sons, whereby we call Abba, Father.” And so the abbot should not—grant that he may not—teach, or decree, or order, any thing apart from the precept of the Lord; but his order or teaching should be sprinkled with the ferment of divine justice in the minds of his disciples. Let the abbot always be mindful that, at the tremendous judgment of God, both things will be weighed in the balance: his teaching and the obedience of his disciples. And let the abbot know that whatever the father of the family finds of less utility among the sheep is laid to the fault of the shepherd… [The abbot] shall make no distinction of persons in the monastery. One shall not be more cherished than another, unless it be the one whom he finds excelling in good works or in obedience. A free-born man shall not be preferred to one coming from servitude, unless there be some other reasonable cause … for whether we be bond or free we are one in Christ; and, under one God, we perform an equal service or subjection; for God is no respecter of persons.