The early centuries of Christianity saw a series of struggles to define the accepted doctrines of the religion—orthodoxy—and to protect them against the challenge of rival or unsound doctrinal ideas—heresy. The first heresies appeared almost as early as the first clergy. In fact, the issue between those who wished to admit gentiles and those who wished to confine the Gospel to the Jews foreshadowed the kind of issue that was to confront Christianity in the first few centuries.

The points at issue sometimes seem unimportant to us today, but we must not regard these religious debates as trivial; people believed that salvation depended upon the proper definition and defense of religious belief and practice. Also, bitter political, economic, and national issues often underlay theological disputes.

It has always been difficult to understand and explain how evil can exist in a world created by a good God. The Gnostics affirmed that only the world of the spirit is real and good; the physical world is evil, or an evil illusion. Thus they could not accept the Old Testament, whose god created this world; they regarded him as a fiend or decided that this world had been created by Satan. Nor could they accept Jesus’ human life, work, and martyrdom in this world—an essential part of Christian belief. They could not accept baptism, because to them water was matter, or venerate a crucifix, which to them was simply two pieces of wood. Like the Zoroastrians, with their god of good and their god of evil, the Gnostics were dualists. Clearly heretical, the Gnostics focused on Christ’s miracles and on other sorts of magic.

Closely related to Gnosticism were the ideas of Mani, a third-century Mesopotamian prophet who called himself the Apostle of Jesus. He preached that the god of light and goodness and his emanations were in constant conflict with the god of darkness, evil, and matter and his emanations. These Manichaean dualistic views became immensely popular, especially in North Africa during the third and fourth centuries. The Christians combated them and throughout the Middle Ages tended to label all doctrinal opposition by the generic term Manichaean.

Within Christianity, heresy sometimes involved very practical problems. The emperor Constantine faced the so- called Donatist movement in North Africa. The movement arose because a number of priests yielded to the demands of Roman authorities during the Roman persecutions of the Christians after 303 and handed the sacred books over to them. After the edicts of toleration of 311 and 313, they had resumed their role as priests. Donatus, bishop of Carthage, and his followers maintained that the sacraments administered by such priests were invalid. This belief was divisive, because once a believer questioned the validity of the sacraments as received from one priest, he might question it as received from any other. Amid much bitterness and violence Constantine ruled that once a priest had been properly ordained, the sacraments administered at his hands had validity, even if the priest himself had acted badly.

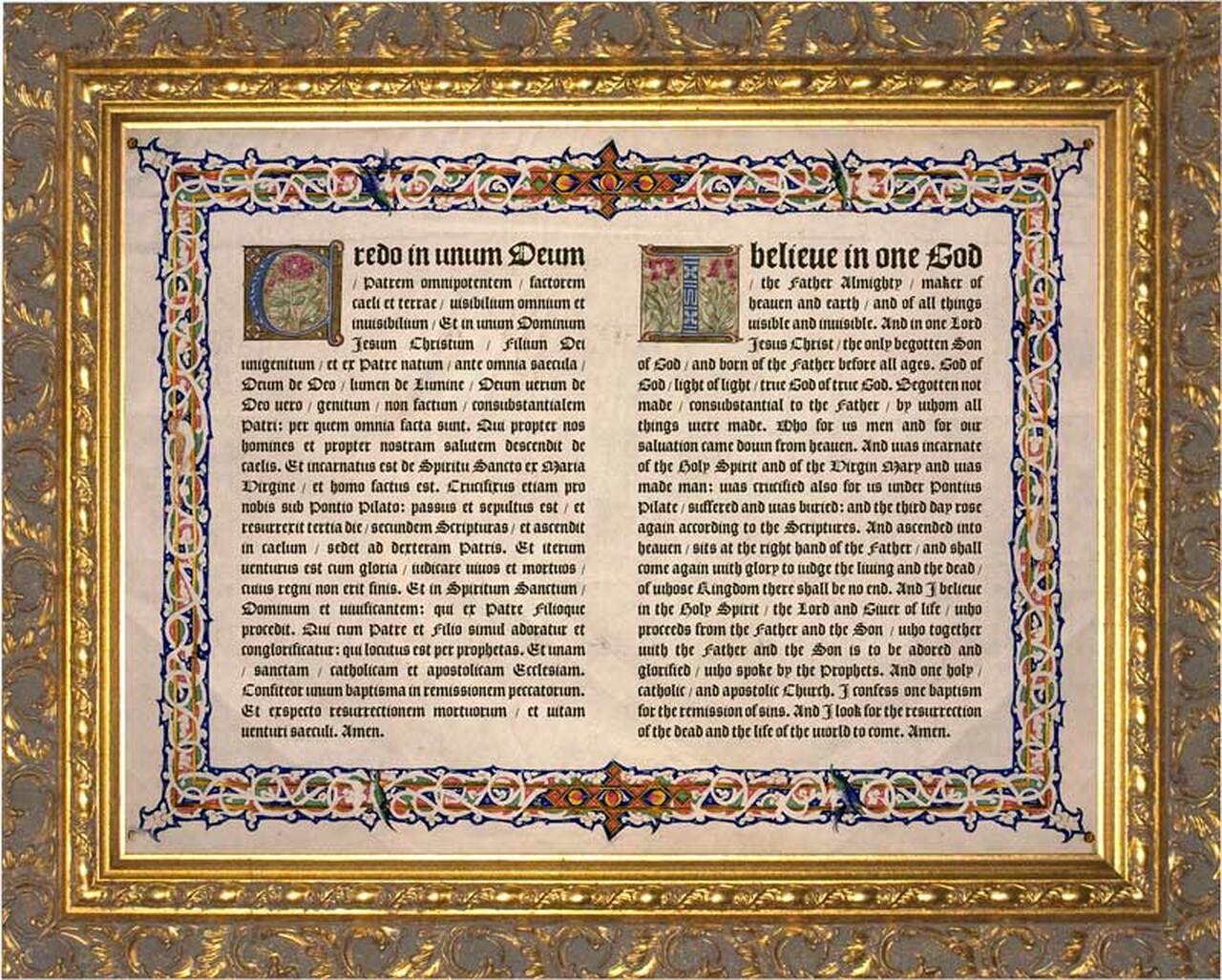

Heresy also arose over essentially philosophical issues. One such was Arianism, named after Arius (c. 280-336), a priest of Alexandria. Early in the fourth century Arius taught that if God the Father had begotten God the Son through God the Holy Ghost, then God the Son, as begot begotten, could not be exactly of the “same essence” (homoousios in Greek) as God the Father, but must be somehow inferior to, or dependent upon, or at the least later in time than his begetter, who was of a “similar essence” (homoiousios in Greek), but not the same. It is difficult to refute this posi¬tion. Far from a quarrel over one letter (homoousios or homoiousios), Arius’s view threatened to diminish the divinity of Christ as God the Son and to separate Christ from the Trinity of Father, Son, and Holy Ghost.

Arius’s bitter opponent, Athanasius (c. 293-373), patriarch of Alexandria and “the father of orthodoxy,” fought him passionately, disdaining logic and emphasizing mystery. Athanasius and his followers maintained that Christians simply had to accept as a matter of faith that Father and Son are identical in essence, and that the Son is equal to, independent of, and contemporaneous with the Father. Even though the Father begat the Son, it was heresy to say that there was ever a time when the Son did not exist. In the Greek East especially, this philosophical argument was fought out not only among churchmen and thinkers but also in the barbershops and among the longshoremen. A visitor to Constantinople complained, “I ask how much I have to pay; they talk of the born and the unborn. I want to know the price of bread; they answer the father is greater than the son.’ I ask if my bath is ready; they say ‘the son has been made out of nothing.'”

After trying to stay out of the quarrel and urging the bishops to stop discussing it, Constantine realized that for political reasons it would have to be settled. In 325 he summoned the first council of the whole church, an ecumenical council, at Nicaea (now Iznik) near Constantinople. A large majority of the bishops decided in favor of the Athanasian view, which was then embodied in the Nicene Creed, issued with all the force of an imperial decree by Constantine himself. The emperor had presided over the council, and against his will found himself assuming the role of head of the church, giving legal sanction to a purely doctrinal decision, and so playing the role both of Caesar and of pope. In time this “Caesaropapism” became the tradition of empire and church in the East.

But the decree of Nicaea did not dispose of Arianism. Arians disobeyed; Constantine himself wavered; his immediate successors on the imperial throne were themselves Arians. Between 325 and 381 there were thirteen more councils that discussed the problem, deciding first one way, then another. One pagan historian sardonically commented that one could no longer travel on the roads because they were so cluttered with throngs of bishops riding off to one council or another. Traces of Arianism remained in the Empire for several centuries after Nicaea.