The provisional government faced a crisis. Kerensky, now war minister, emerged as the dominant leader. He failed to realize that it was no longer possible to restore the morale of the armies. A new offensive ordered on July 1 collapsed as soldiers refused to obey orders, deserted their units, and hurried home to their villages, eager to seize the land. The soviets became gradually more and more Bolshevik in their views. Although the June congress of soviets in Petrograd was less than 10 percent Bolshevik, the Bolshevik slogans of peace, bread, and freedom won overwhelming support.

An armed outbreak by troops who had accepted the Bolshevik slogans found the Petrograd Soviet professing unwillingness to assume power. While crowds roared outside, the Soviet voted to discuss the matter two weeks later and meanwhile to keep the provisional government in power. The government declared that Lenin was a divisive agent of Germany, and Lenin went into hiding in Finland to avoid arrest.

Kerensky became premier. General Lavr Georgyevich Kornilov (1870-1918), chosen by Kerensky as the new commander in chief of the armies, quickly became the hope of all conservative groups. In August Kornilov plotted a coup, intending to disperse the Soviet. His attitude toward the provisional government was less clear, but had he succeeded he would probably have demanded a purge of its more radical elements. Tension between Kornilov and his superior, Kerensky, mounted. The Soviet backed Kerensky, fearing Kornilov’s attack. When Kornilov refused to accept his dismissal as war minister and seemed about to march against Petrograd, the Bolsheviks threw themselves into preparations for defense. Kornilov’s troop movements were sabotaged, however, and by September 14 he had been arrested.

The Kornilov affair turned the army mutiny into a widespread revolt. In the countryside farms were burned, manor houses destroyed, and large landowners killed. After the great estates were gone, the peasantry attacked the smaller properties, though they allowed owners in some districts to keep a portion of their former lands through redistribution.

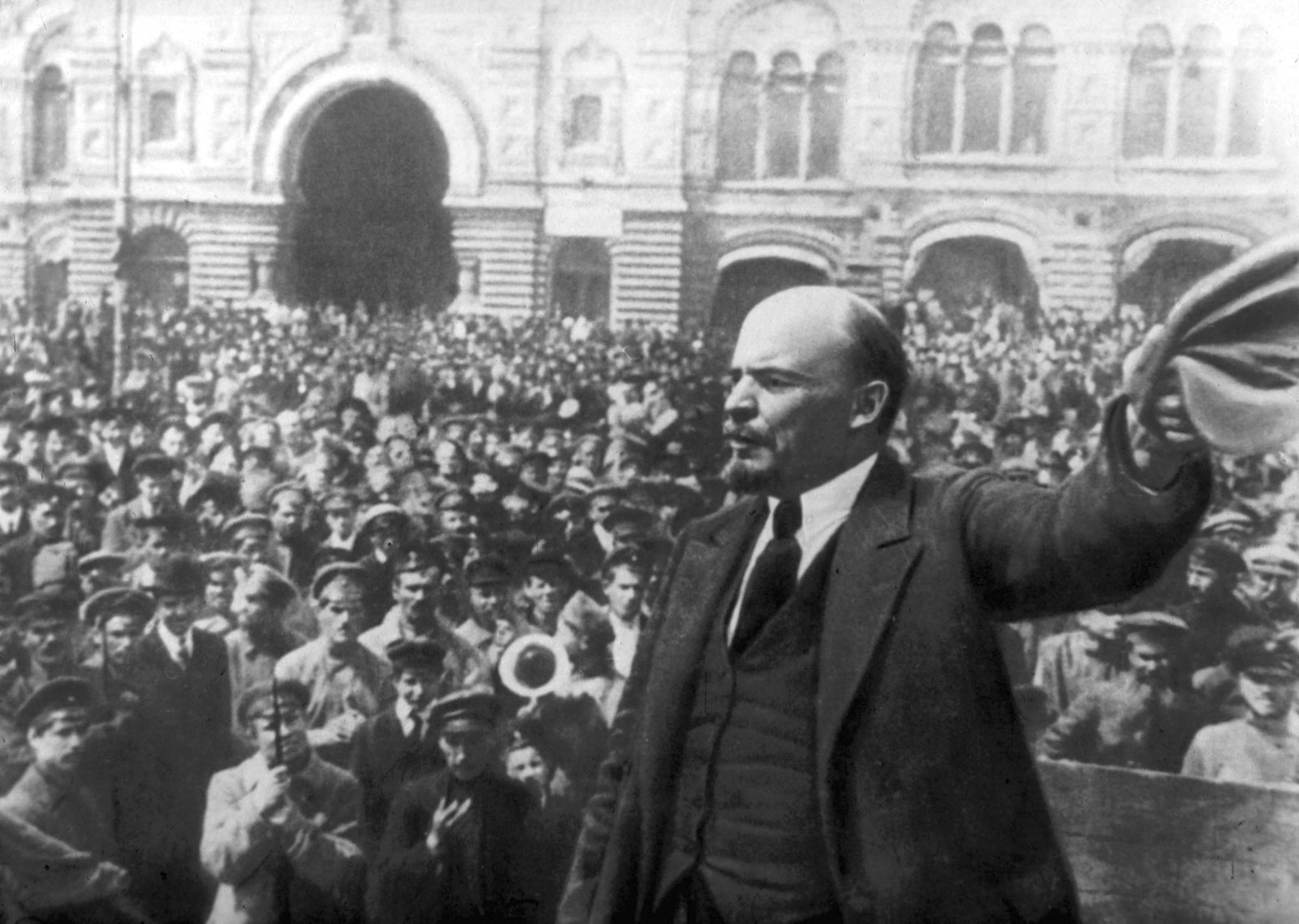

Amid these disorders Lenin returned to Petrograd. Warning that Kerensky was planning to surrender Petrograd to the Germans, Trotsky gained control over a Military Revolutionary Committee to help defend the city and to transform the committee into a general staff for the revolution. Beginning on November 4, he addressed huge demonstrations and mass meetings, and on November 7 (October 25 on the old Russian calendar) the insurrection broke out as Trotsky intended. The February Revolution had failed, to be replaced by the October Revolution.

In Petrograd the revolution had been well prepared and proceeded with little bloodshed. Military groups loyal to the Bolsheviks took control of key points in the city. The Bolsheviks entered the Winter Palace, where the provisional government was meeting, and arrested the ministers. Kerensky escaped and the Military Revolutionary Committee took over. A long-awaited Congress of Soviets, representing less than half of the soviets in Russia, opened on November 8. Both Lenin and Trotsky appeared.

When the Mensheviks and right-wing SRs walked out, Trotsky called them garbage that would be swept into the trash cans of history. Cooperating with the left-wing SRs and adopting their land program, Lenin abolished the property rights of the church, of landlords, and of the Crown. He transferred the land thus affected to local land committees and soviets of peasant deputies, transforming at a stroke the isolated Russian villages by “legalizing” a process already begun. He also urged an immediate peace without annexations or indemnities and appealed to the workers of Germany, France, and England to support him in this demand. Finally, a new cabinet, called a Council of People’s Commissars, was chosen, with Lenin as president and Trotsky as foreign commissar.

The Bolsheviks installed as commissar of nationalities a younger man, a Georgian named Joseph Dzhugashvili (1879-1953), who had taken the name Stalin, suggesting a steel-like hardness. Under Lenin’s coaching, Stalin had become the party authority on questions relating to the many minority nationalities and had published a pamphlet on the subject in 1913.

Outside Petrograd the revolution moved more slowly. In Moscow there was a week of street fighting between Bolshevik Reds and anti-Bolshevik Whites, as those opposed to the revolution were called. Elsewhere, in factory towns the Bolsheviks usually won speedily; in nonindustrial centers it took longer. A main reason for the rapid and smooth success of the Bolsheviks was that the provincial garrisons opposed the war and willingly allied themselves with the workers.

Local military revolutionary committees were created in most places and held elections for new local soviets. Most of Siberia and central Asia came over, but Tiflis, the capital of Georgia, went Menshevik and passed resolutions calling for a constituent assembly and the continuation of the war. Gradually the town of Rostov-on-Don, near the Sea of Azov, became the main center of White resistance, as Kornilov and other generals together with a number of the leading politicians of the Duma gathered there.

Late in November an agreement was reached with the left-wing SRs, three of whom entered the government, and peace negotiations were begun with the Germans. The revolution proper was over and Lenin was in power. The Russian state, however, was disintegrating and decomposing socially on all sides. On November 25 the Bolsheviks held elections for a constituent assembly, the first free election in Russian history. As was to be expected, the Bolshevik vote was heaviest in the cities, especially Moscow and Petrograd, while the SR vote was largely rural.

Disregarding the fact that 62 percent of the votes had been cast for his opponents, Lenin maintained that “the most advanced” elements had voted for him. The constituent assembly met only once, in January 1918. Lenin dissolved it the next day by decree and sent guards with rifles to prevent its meeting again.

The anti-Bolshevik majority was deeply indignant at this unconstitutional act of force against the popular will, but there was no public outburst and the delegates disbanded. In part this was because the Bolsheviks had already taken action on what interested the people most—peace, bread, and freedom—and in part because the Russian masses lacked a democratic parliamentary tradition.