The Last Two Wars of King Louis XIV | The Problem of Divine-Right Monarchy

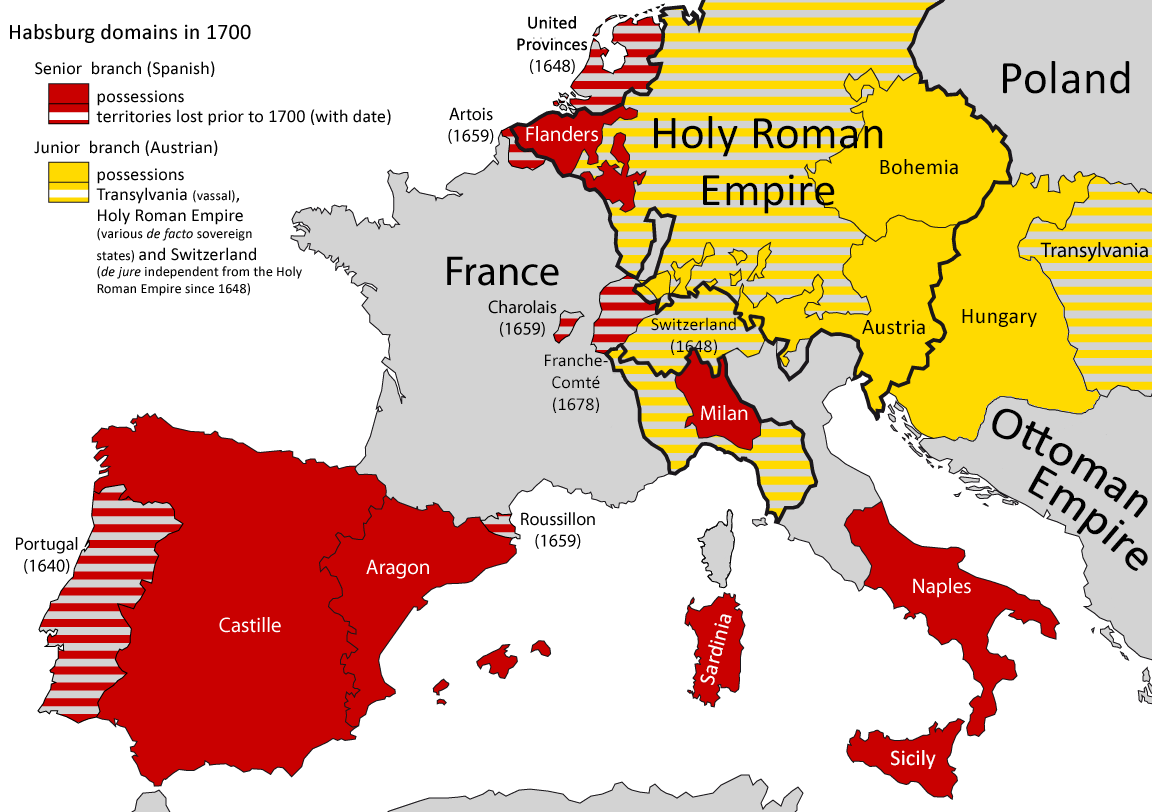

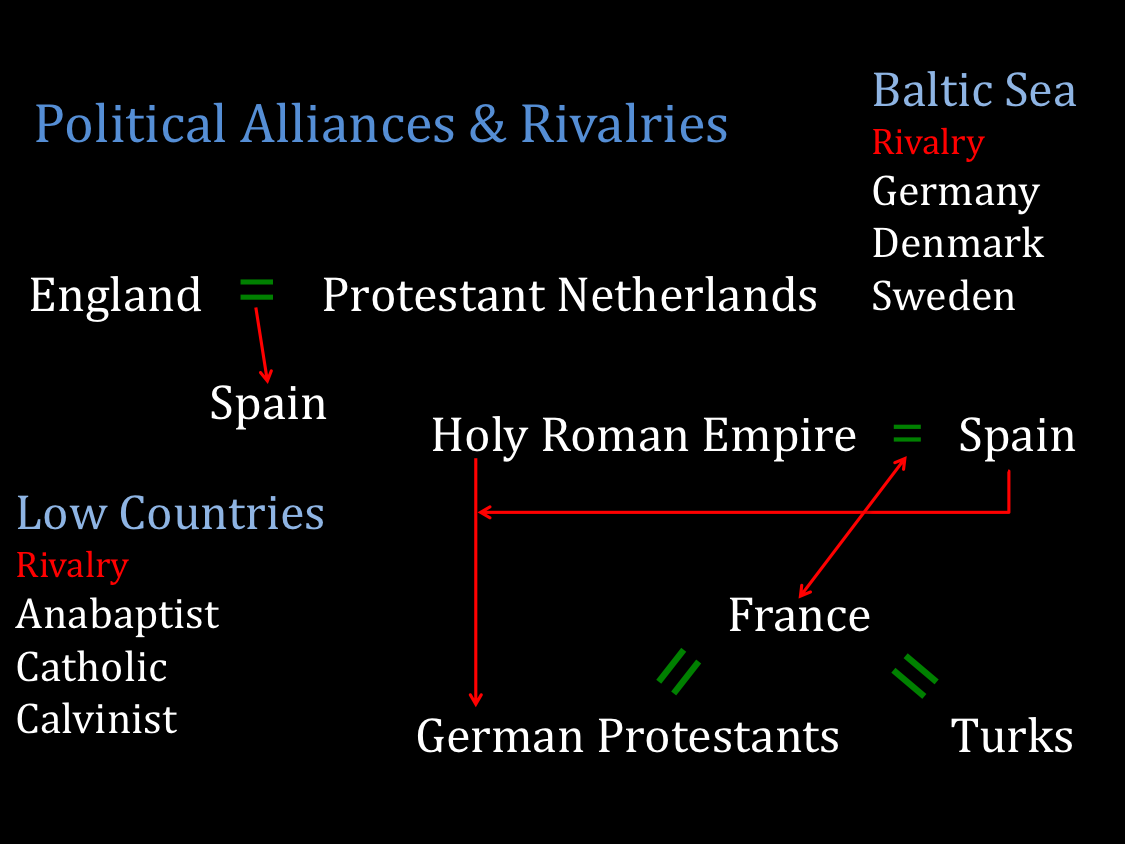

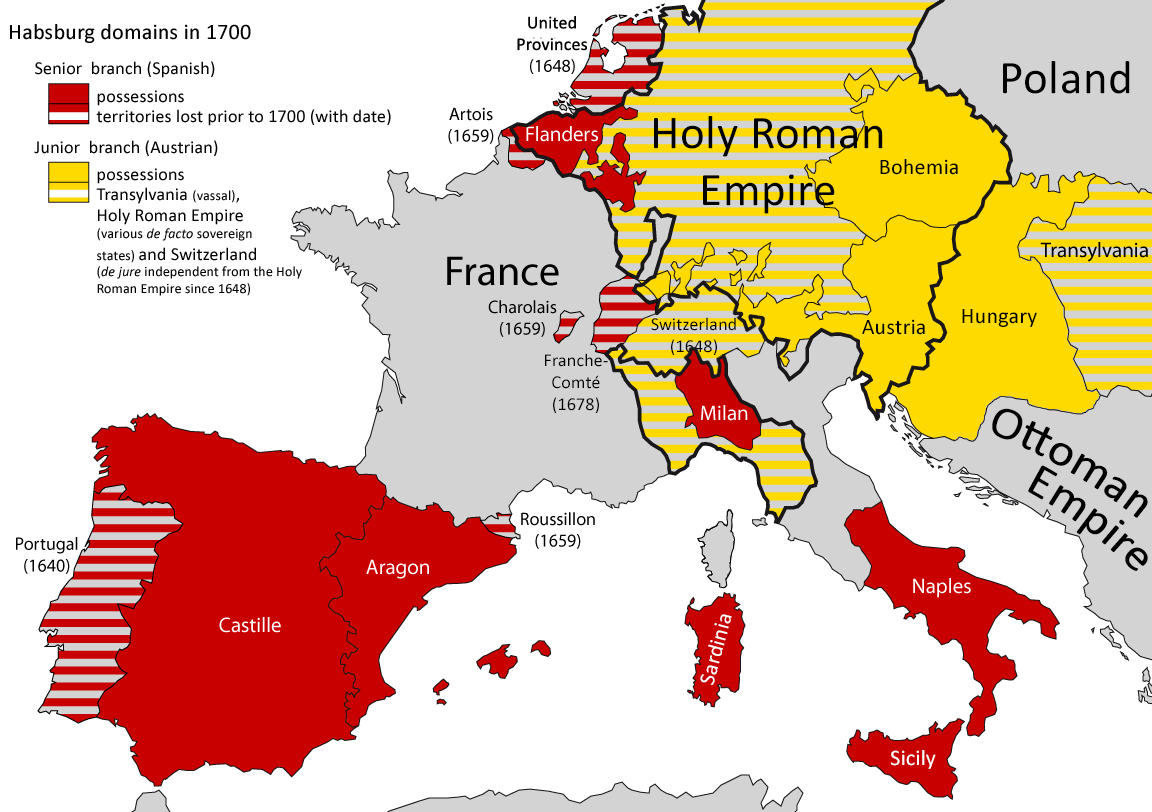

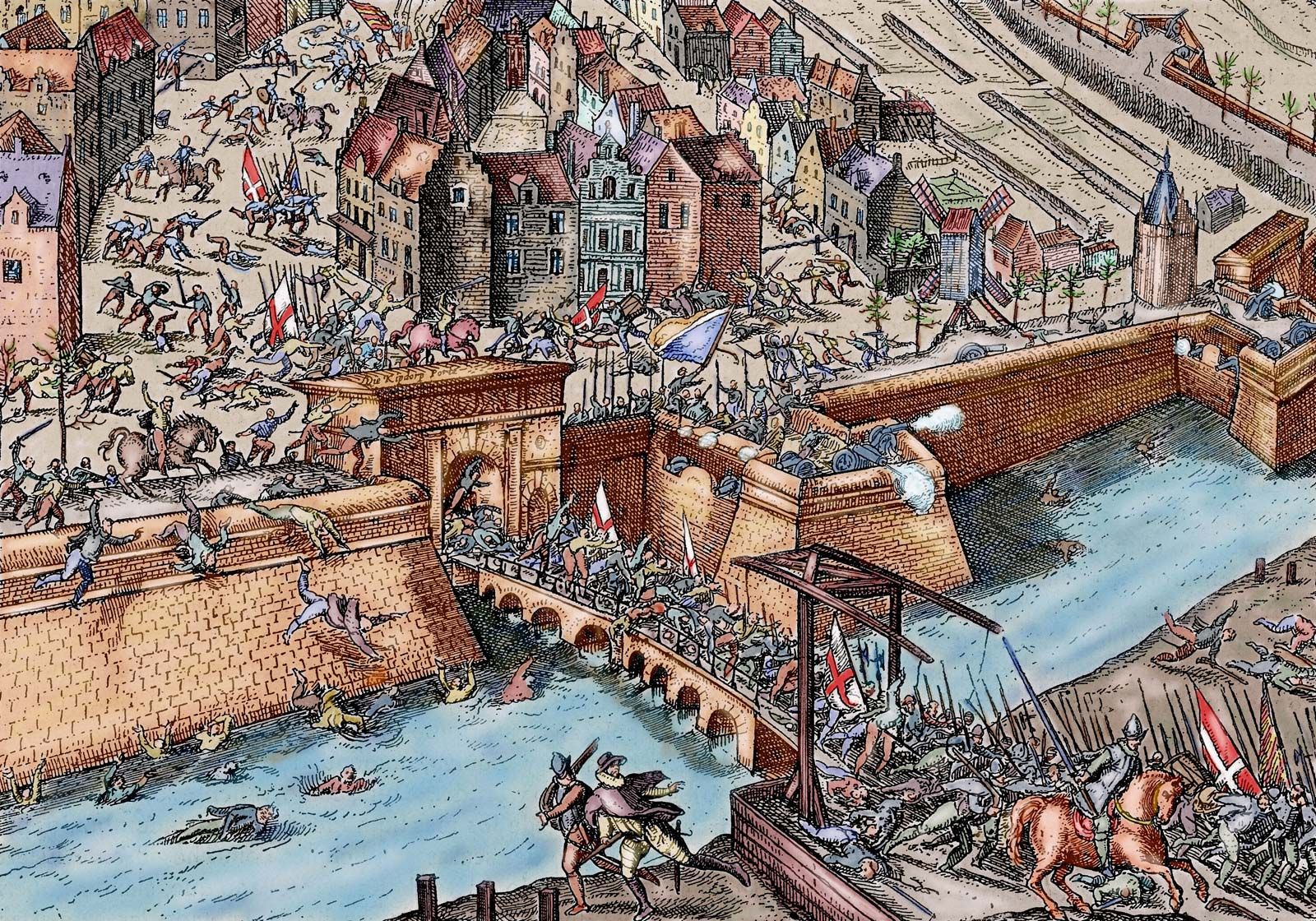

But in the last three decades of Louis’s reign most of his assets were consumed. Not content with the prestige he had won in his first two wars, Louis took on most of the Western world in what looked like an effort to destroy the independence of Holland and most of western Germany and to bring the Iberian peninsula under a French ruler.