The French Revolution was the most fundamental event of the nineteenth century, and its meaning, its causes, and its impact continue to be debated.

One debate is whether there was an autonomous peasant revolution directed against feudalism imbedded within the larger revolution, with the peasants seeking their own road to capitalism. Clearly hostility to harvest dues and other seigneurial burdens had unified many rural communities to the point that protests continued well after the National Assembly had declared feudalism abolished.

But peasants did not generally take a stand for or against the republic, and while administrative changes had a deep effect on rural society, peasants continued to favor collective use of the land. On the whole the rhetoric of revolutionaries in Paris had little influence on seigneurial obligations, especially when fiscal problems forced the revolutionaries to abandon efforts to privatize common lands.

While peasants near Paris did demand individual allotments from the commons, such changes do not appear to have been widespread. Nonetheless, for the peasantry the Revolution brought significant changes, especially in southern France, by abolishing the seigneurial system, encouraging birth control, creating formal municipal institutions, reforming the judicial system, and reducing fiscal inequities.

Another debate is over the role of women in the revolution. Working through a variety of power brokers, many women sought to achieve greater equality, to break from the church, and to play political roles, if largely behind the scenes. Ultimately the Revolution deeply disappointed them, and the most articulate of the women made it clear that they considered their hopes had been betrayed, that “prosperity” for some was not prosperity for them.

Perhaps the most overriding debate is between the Marxists and non-Marxists, and within each school, between early analysts and revisionists. Often these debates turn upon preconceptions of the nature of human motivation, sometimes on the nature of language and the intent, as opposed to the performance, of specific individuals and groups.

Often the debate is over the relative significance of cultural and political factors as opposed to social and economic, or over the extent to which even this most revolutionary of revolutions was evolutionary. As study of the French Revolution has broadened and deepened, especially during the observation of the Revolution’s bicentennial in the 1980s, historians have come to realize how difficult generalization can be: what was true for Paris was not true for Bordeaux; the revolt of 1793 in Lyons arose from causes in some significant measure different from events in Marseilles. Thus the French Revolution continues to be eternally fascinating, eternally studied, and eternally debatable.

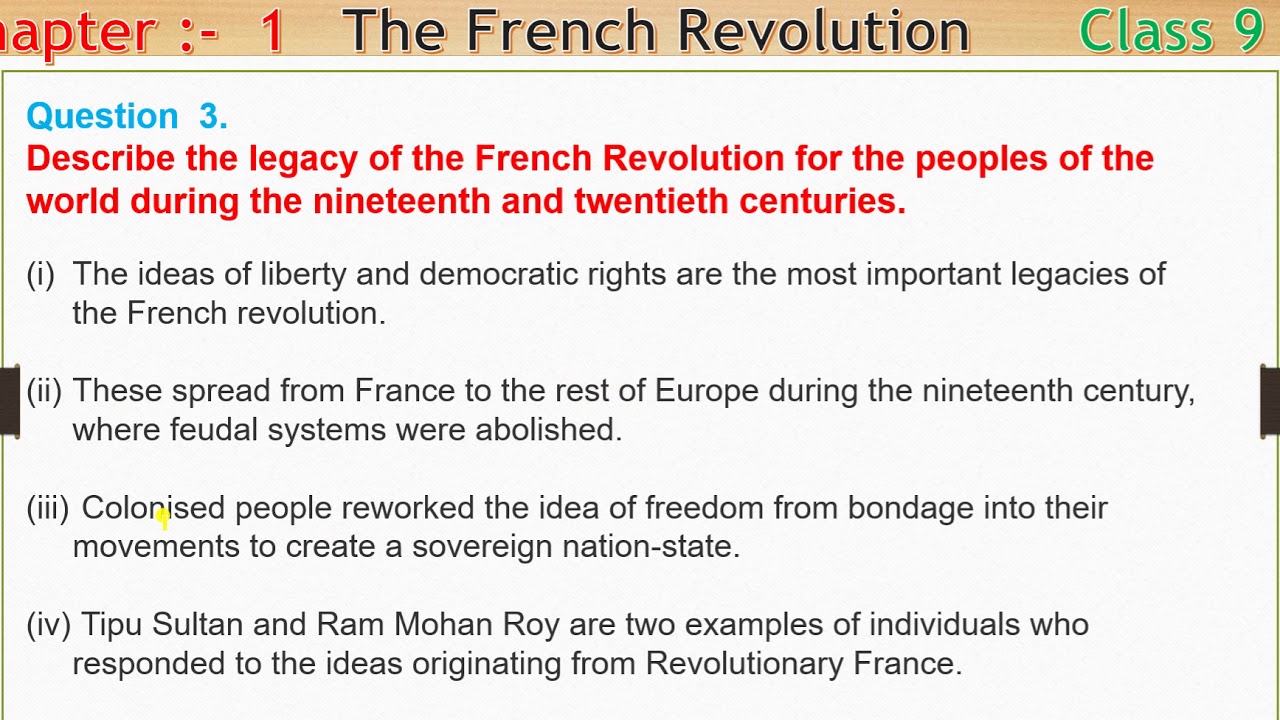

The Napoleonic legend, with its hero worship and belligerent nationalism, was one element in the legacy bequeathed by revolutionary and Napoleonic France. A second and much more powerful element was the great revolutionary motto—Liberte, Egalite, Fraternité—which inspired later generations in France and elsewhere.

Behind the motto was the fact that the French, though not yet enjoying the full democracy of the twentieth century, enjoyed greater liberty, equality, and fraternity in 1815 than they had ever known before 1789. Although French institutions in 1815 did not measure up to the ideals of liberty expressed in the Declaration of the Rights of Man, the ideals had been stated.

The revolutionary and Napoleonic regimes established the principle of equal liability to taxation. They provided more economic opportunity for the third estate by removing obstacles to the activity of business people and by breaking up the large estates of the clergy and nobility; these lands passed mainly to the urban bourgeois and the well-to-do peasants.

The only gesture toward full equality of property was the Laws of VentOse of 1794, and they were never implemented. The Revolution was an important step in the ascendancy of middle-class capitalism, both urban and rural. In this sense the work of the Revolution was not truly democratic, since the sans- culottes had apparently gained so little. Yet the Code Napoleon did bury beyond all hope of return the worst legal and social inequalities of the Old Regime.

The Revolution and Napoleon promoted fraternity in the legal sense by making all French men equal in the eyes of the law. In a broader sense they advanced fraternity by encouraging nationalism, the feeling of belonging to a great corporate body, France, that was superior to all other nations. The Napoleonic empire then showed how easily nationalism on an unprecedented scale could lead to imperialism of unprecedented magnitude.