Years of fiscal mismanagement contributed to the severe financial crisis that precipitated the French Revolution. Louis XVI, irresolute and stubborn, was unable to meet the overwhelming need for reform. The third estate, which constituted over 97 percent of the population, held some land, but rural poverty was widespread.

Moreover, this estate bore the heavy burden of taxation. Discontent was rife among urban workers. The bourgeoisie helped focus this discontent against the privileged estates and called for an end to the abuses of the Old Regime, especially the inequalities of tax assessments.

The financial emergency of the heavily indebted monarchy forced the king to summon the Estates General. Bad weather and poor harvests in the winter of 1788-1789 led to demands for drastic change. When the Estates General met, the third estate successfully challenged the king over procedure, transforming the Estates General into a National Assembly charged with writing a constitution.

Popular uprisings pushed the Revolution along at an increasing pace. The National Assembly abolished the abuses of the Old Regime and in August 1789 issued the Declaration of the Rights of Man, embodying the ideals of the Enlightenment.

By 1791 the National Assembly had completed its task and established a government based on a separation of powers. The activities of French emigres and of Louis XVI and the outbreak of war in 1792 opened a gulf between moderates and extremists. In Paris the Jacobins led a municipal revolution that resulted in the abolition of the monarchy.

In 1793 Robespierre, an advocate of democracy, imposed a dictatorship on France. During the Reign of Terror twenty thousand were killed. Calling for total mobilization and economic sacrifice, Robespierre and the Committee of Public Safety organized a drive to push foreign invaders from France.

The excesses of the Terror created the conditions for Robespierre’s downfall in July 1794. A new Constitution of 1795 established the Directory, which assured the dominance of the propertied classes.

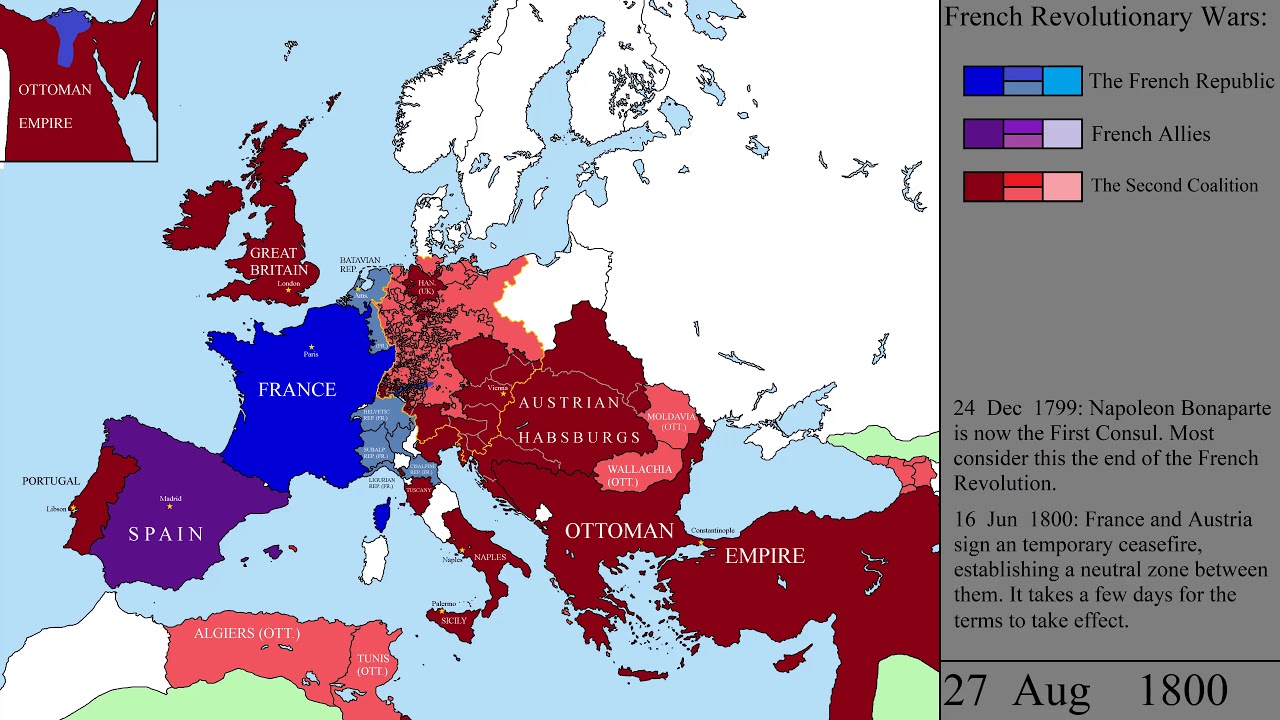

In 1799 Napoleon engineered a coup d’etat ending the Directory and establishing the Consulate. Napoleon became first consul for life in 1802 and emperor in 1804. He moved quickly to centralize imperial administration and appointed talented ministers to office.

The Code Napoleon embodied some ideas of the Old Regime as well as revolutionary principles such as the equality of all citizens before the law.

In religion, Napoleon made peace with the church in the Concordat of 1802. Education was subservient to the state, with lycees established to train administrators. Napoleon established the Bank of France and improved tax collection.

In Europe, Napoleon built a vast empire. He forced Prussia, Russia, and Austria to accept peace terms, leaving only Britain in the war against France. The French Empire was divided into three parts: France and the territories it annexed; French satellite states; and Austria, Prussia, and Russia. In Germany, Napoleon formally dissolved the Holy Roman Empire and created the Confederation of the Rhine.

Napoleon’s effort to wage economic warfare against Britain backfired, hurting France and antagonizing neutral powers. Nationalist movements in Spain and Prussia threatened the French Empire after 1808.

When Napoleon’s Russian campaign of 1812 ended in disaster for his Grand Army, the nations of Europe formed a new coalition that presided over Napoleon’s downfall. In 1814 the Bourbons were restored to power. The Napoleonic legend, however, would haunt France, as would the revolutionary goals of liberty, equality, and fraternity.