The divergent beliefs and practices that separated the Protestant churches one from another may be arranged most conveniently in order of their theological distance from Catholicism. The Church of England managed to contain almost the whole Protestant range, from High Church to extreme Low Church.

Yet it retained a form of the Catholic hierarchy, with archbishops and bishops, though without acknowledging the authority of the pope. Perhaps the central core of Anglicanism became a tempered belief in hierarchy and authority from above, a simplified ritualism, and a realistic acceptance of an imperfect world.

But there has also been a strong puritanical current in Anglicanism. Puritanism, which may be defined as a combination of plain living and high thinking with earnest piety, was an important variant of the Low Church attitude. While some Puritans reluctantly left the Anglican communion in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century, many others remained within it.

The Church of England assumed its definitive form during the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603), daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn. The Thirty-nine Articles enacted by Parliament in 1563 were a kind of constitution for the church. The Articles rejected the more obvious forms of Romanism: the use of Latin, confession to a priest, clerical celibacy, the allegiance to the pope. They also affirmed the Protestant stand on one of the great symbolic issues of the day—the Eucharist—by giving both the bread and the wine to communicants, as the reformers had long demanded, in contrast to the Catholic custom of giving only the wafer. Finally, the Thirty-nine Articles sought to avoid the anarchistic dangers implicit in the doctrines of justification by faith and the priesthood of the believer.

The Church of England has always seemed Erastian, so called after Thomas Erastus (1524-1583), a Swiss theologian and a disciple of Zwingli who objected to the theocratic practices of the Calvinists. Erastus wanted to increase the power of the political authorities to check abuses by the religious authorities. The term Erastianism, however, has come to imply that the state is all-powerful against the church and that the clergy should be simply a moral police force. While Anglicanism seldom went this far in practice, a modified Erastianism does remain in the Church of England.

To outsiders the Lutheran church has appeared even more Erastian than the Anglican. As the state church in much of northern Germany and in Scandinavia, it was often a docile instrument of its political masters. And in its close association with the rise of Prussia it was brought under the rule of the strongly bureaucratic Prussian state.

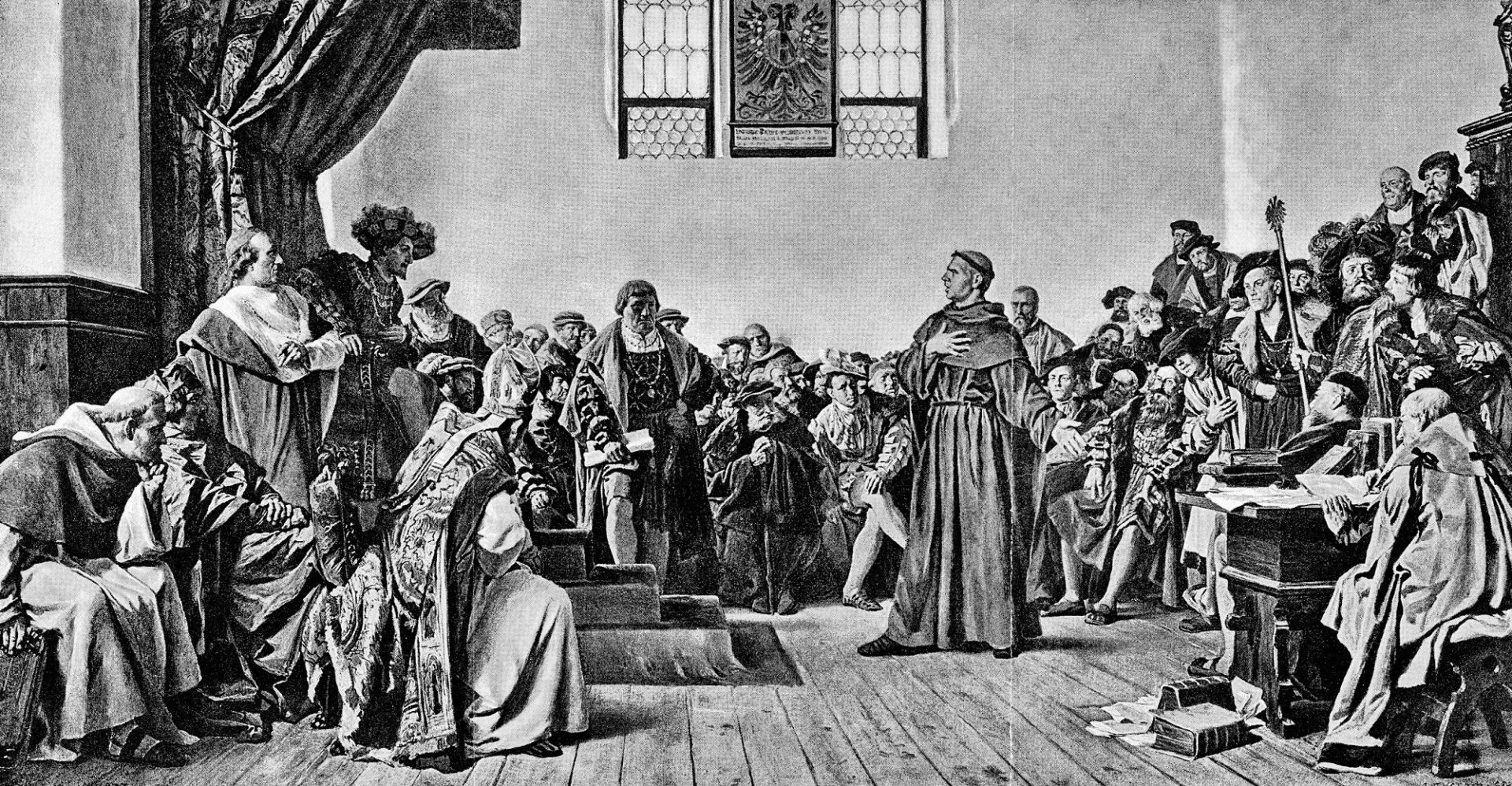

Luther was at heart a conservative. He wanted the forms of Lutheran worship to recall the forms he was used to. Once it had become established, Lutheranism preserved many practices that seem Catholic in origin but that to Luther presented a return to early Christianity before the corruption by Rome.

Lutheranism preserved the Eucharist, now interpreted by the doctrine of consubstantiation. The tradition of good music in the church was not only preserved but greatly fortified. The Lutheran church, however, had a strong evangelical party as well as a conservative high church party.