-

Pope Leo XIII Attacks Socialism

Pope Leo XIII was concerned with issues of liberty and political power. He was sympathetic to the plight of the workers and felt that the Church should recognize their concerns, though he did not believe in the inevitable clash of labor and capital. Thus in Rerum novarum he wrote that it was a “great mistake”…

-

Anarchists | The Industrial Society

Other apostles of violence called themselves anarchists, believing that the best government was no government at all. For them it was not enough that the state should wither at some distant time, however; such an instrument of oppression should be annihilated at once. The weapon of the anarchist terrorists was the assassination of heads of…

-

Apostles of Violence and Nonviolence | The Industrial Society

The various forms of liberalism and socialism did not exhaust the range of responses to the economic and social problems created in industrial societies. Nationalists reinvigorated old mercantilist ideas, not only advocating tariffs to protect agriculture and industry but also demanding empires abroad to provide new markets for surplus products, new fields for the investment…

-

Marxism after 1848 | The Industrial Society

From 1849 until his death in 1883, Marx lived in London, where, partly because of his own financial mismanagement, his family experienced the misery of a proletarian existence in the slums of Soho.

-

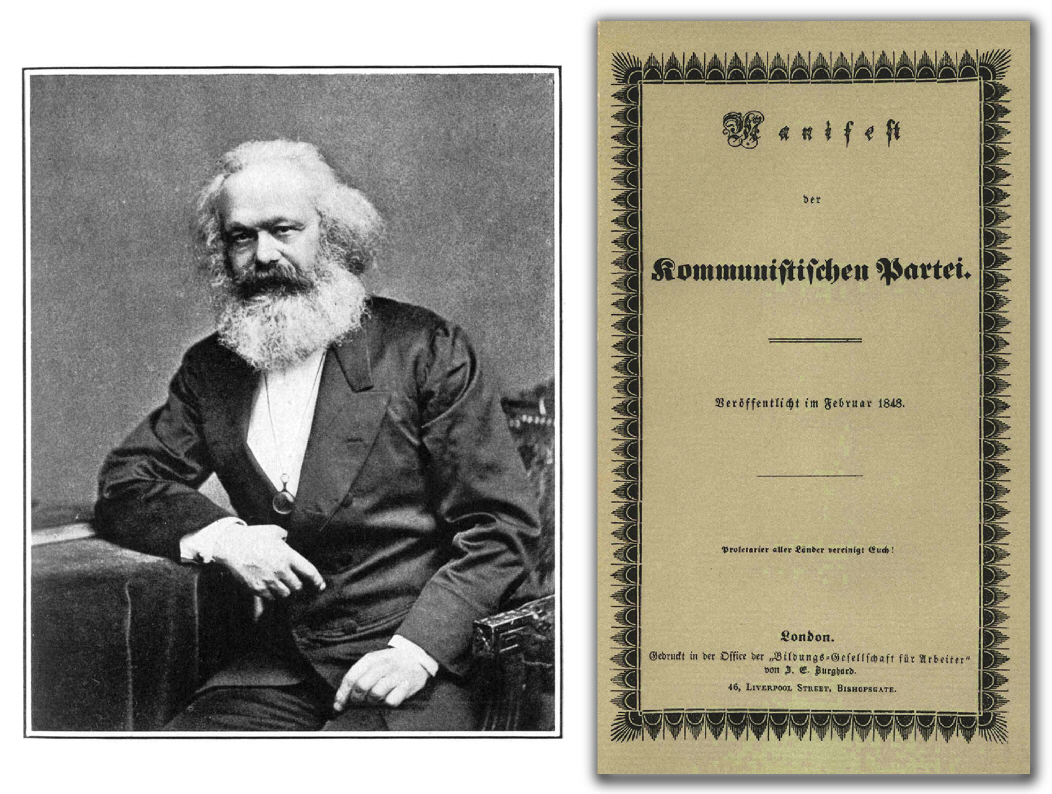

Friedrich Engels and The Communist Manifesto | The Industrial Society

Meanwhile, Marx began his friendship and collaboration with Friedrich Engels (1820-1895). In many ways, the two men made a striking contrast.

-

Karl Marx (1818-1883) | The Industrial Society

With Karl Marx (1818-1883) socialism moved to a far more intense form—revolutionary communism. Whereas the early socialists had anticipated a gradual and peaceful evolution toward Utopia, Marx forecast a sudden and violent proletarian uprising by which the workers would capture governments and make them the instruments for securing proletarian welfare. From Blanc he derived the…

-

The Utopians | The Industrial Society

Utopian socialists derived their inspiration from the Enlightenment. If only people would apply reason to solving the problems of an industrial economy, if only they would wipe out artificial inequalities by letting the great natural law of brotherhood operate freely—then utopia would be within their grasp, and social and economic progress would come about almost…

-

Socialist Responses: Toward Marxism | The Industrial Society

In his later years, Mill referred to himself as a socialist; by his standard, however, most voters today are socialists. Universal suffrage for men and for women, universal free education, the curbing of laissez faire in the interests of the general welfare, the use of the taxing power to limit the unbridled accumulation of private…

-

Humanitarian Liberalism | The Industrial Society

John Stuart Mill grew up in an atmosphere dense with the teachings of utilitarianism and classical economics. From his father, he received an education almost without parallel for intensity and speed. He began the study of Greek at three, was writing history at twelve, and at sixteen organized an active Utilitarian Society. At the age…

-

The Utilitarians | The Industrial Society

One path of retreat from stark laissez-faire doctrines originated with Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832), an eccentric philosopher. Bentham founded his social teachings on the concept of utility: that the goal of action should be to achieve the greatest good for the greatest number.

-

The Classical Economists | The Industrial Society

Educated for the ministry, Malthus became perhaps the first professional economist in history; he was hired by the East India Company to teach its employees at a training school in England. In 1798 he published his Essay on Population, a dramatic warning that the human species would breed itself into starvation. In the Essay, Malthus…

-

The Responses of Liberalism | The Industrial Society

Faced with the widening cleavage, both real and psychological, between rich and poor, nineteenth-century liberals at first held to the doctrine of laissez faire: Suffering and evil are nature’s admonitions; they cannot be got rid of and the impatient attempts of benevolence to banish them from the world by legislation . . . have always…

-

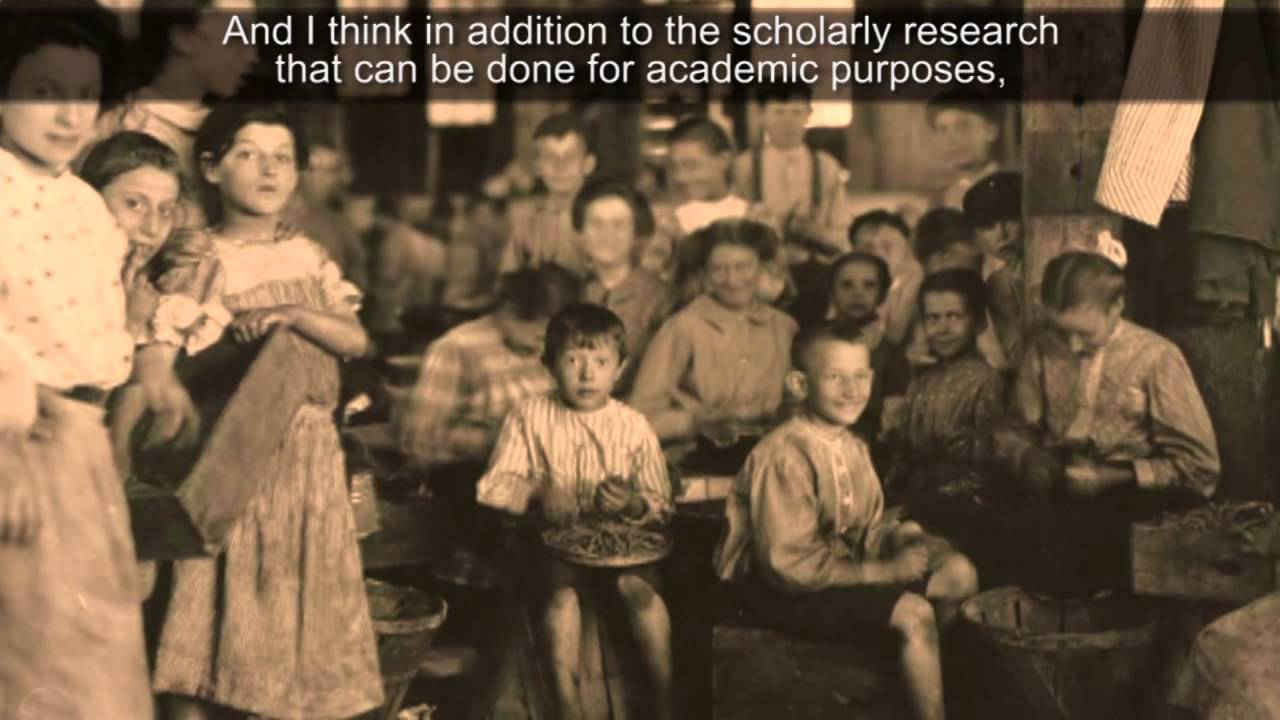

A Day at the Mills

Frequently, entire families had to work as a matter of sheer economic necessity. A factory worker testified before a British parliamentary committee in 1831-1832: At what time in the morning, in the brisk time, did those girls go to the mills? In the brisk time, for about six weeks, they have gone at 3 o’clock…

-

Class Grievances and Aspirations | The Industrial Society

In the Britain of the 1820s, the new industrialists had small opportunity to mold national policy. Booming industrial cities like Manchester and Birmingham sent not a single representative to the House of Commons. A high proportion of business leaders belonged not to the Church of England but were nonconformists who still suffered discrimination when it…

-

The Experience of Immigration

The movement of people from one land to another, from one continent to another, has marked history since antiquity, and today is one of the most notable realities of a world in a steady state of enormous change. Entire societies have moved from one place to another; millions of individuals change the place where they…

-

The Population Explosion and the Standard of Living | The Industrial Society

When Britain abandoned any pretense of raising all the basic foods its people needed, its population was growing so rapidly that self-sufficiency was no longer possible. The number of inhabitants in England and Wales more than tripled during the nineteenth century, from about 9 million in 1800 to 32.5 million in 1900.

-

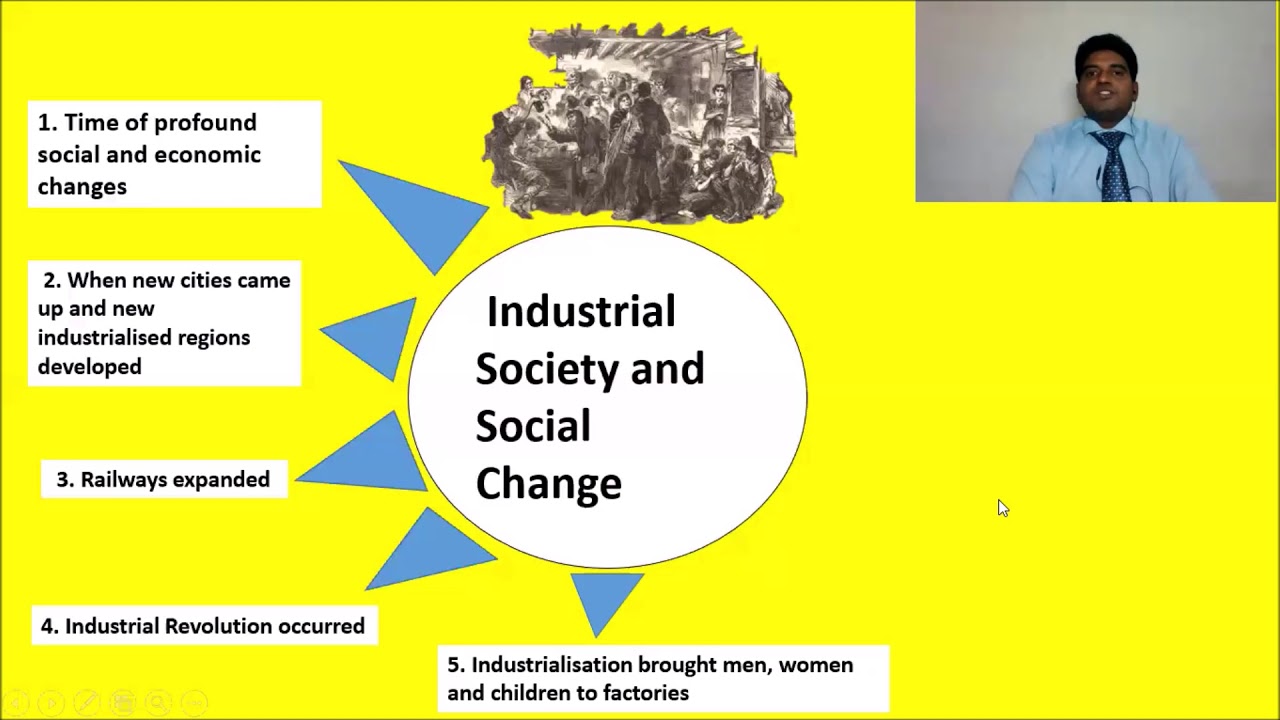

Economic and Social Change | The Industrial Society

With industrialization there came a population explosion, a dramatic rise in the standard of living for many (and harsh, but different, conditions for others), and a desire to have greater control over birth and death rates. This desire expressed itself through the state and also in a social demand for improved working conditions.

-

British Decline | The Industrial Society

After 1850 Britain began to lose its advantage. Politically its leaders had positioned it well to the forefront. The Reform Act of 1832 had put Parliament into the hands of the propertied classes, which proceeded to pass legislation favorable to industry.

-

Money, Banking, and Limited Liability | The Industrial Society

The exploitation of these new developments required a constant flow of fresh capital. From the first, the older commercial community supported the young industrial community. Bankers played such an important role that the Barings of London and the international house of Rothschild were among the great powers of Europe.

-

Transport and Communication | The Industrial Society

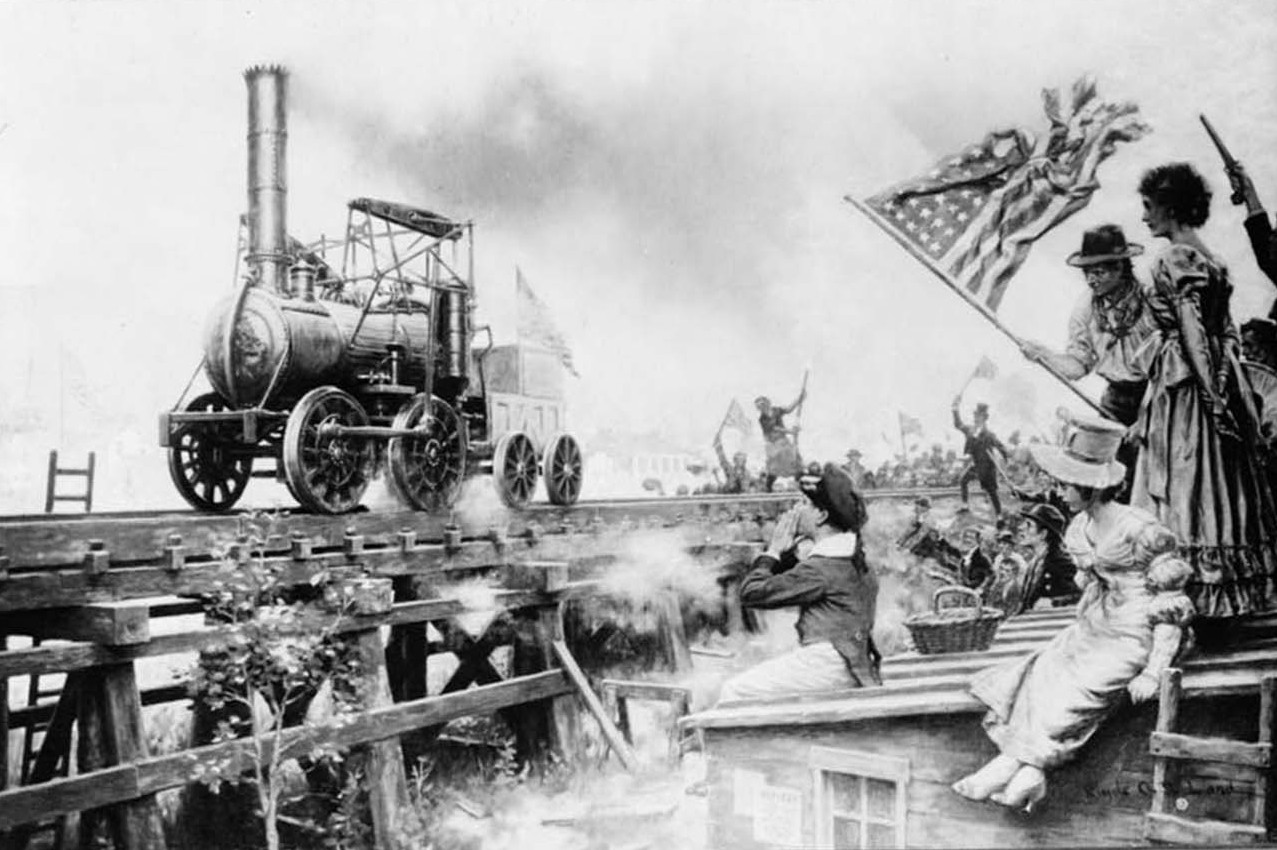

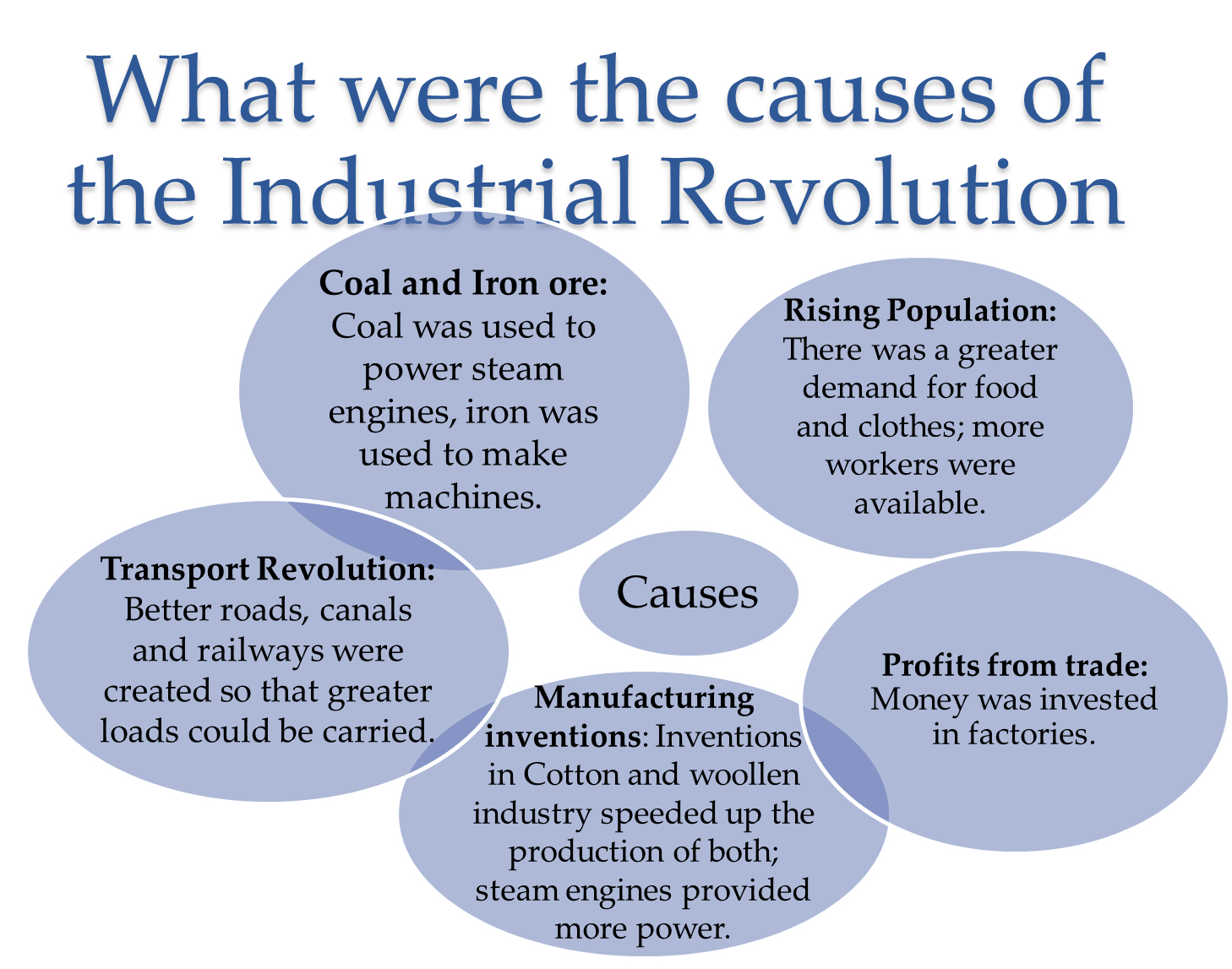

Steam, coal, and iron brought the railway age. Coal powered the railways and the railways carried coal. Though railways based on wooden rails were known from the sixteenth century, iron and steel rails made it possible to carry huge weights and mount giant locomotives to pull long trains.

-

Textiles, Coal, and Iron | The Industrial Society

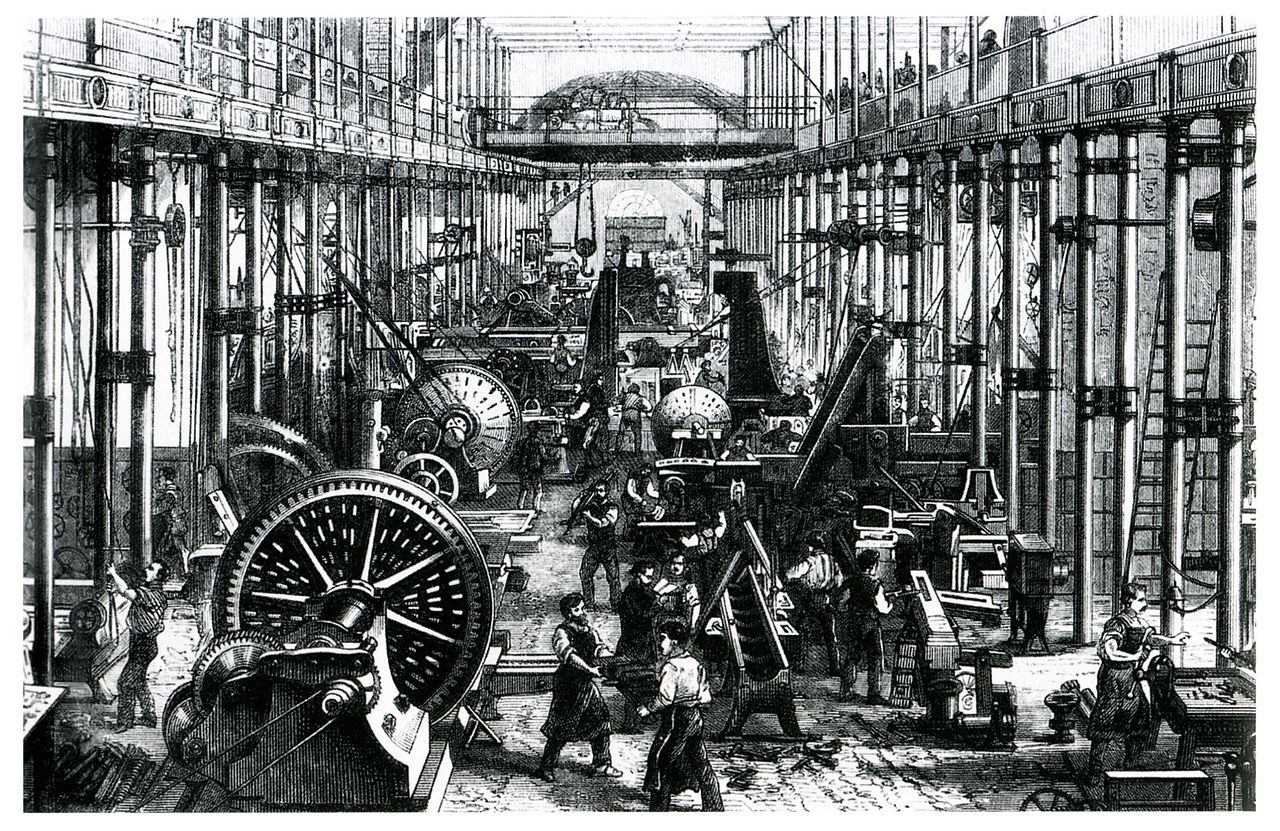

The textile industry was the first to exploit the potentialities of power-driven machinery. Beginning with the spinning jenny in the 1760s, the use of machinery gradually spread to other processes.

-

British Leadership, 1760-1850 | The Industrial Society

The process of industrialization began in Britain. After the 1760s England enjoyed a long period of relative economic prosperity. Starting in the sixteenth century, a new group of landed proprietors—squires and townspeople— saw land as an investment; thus they were concerned with improved production and profit.

-

Stages of Industrial Growth | The Industrial Society

Economic change generally takes place gradually, and therefore some historians feel it is misleading to speak of an industrial revolution, since the process was clearly evolutionary, rather than revolutionary.

-

The Industrial Society

When the Liverpool and Manchester Railway line opened in September of 1830, the railway train—drawn by the Rocket, then the fastest and strongest of the locomotives—ran down and killed William Huskisson, a leading British politician and an ardent advocate of improving transport and communication, who had under-estimated its speed. This, the first railway accident in…

-

Summary | Romanticism, Reaction, and Revolution

Romanticism, materialism, and idealism overlapped as strands of thought in a period of rapid change. Romantics rejected the narrow optimism and mechanistic world of Enlightenment rationalists. The style of the romantics was imaginative, emotional, and haunted by the supernatural and by history. They stressed the individual and emotional ties to the past.

-

The Habsburg Domains | The Revolutions of 1848

The fate of German and Italian nationalism in 1848 hinged partly on the outcome of the revolutions in the Habsburg Empire. If these revolutions had immobilized the Habsburg government for a long period, the Italian and German unification might have been realized. But Austria rode out the storm. The success of the counterrevolution in the…

-

Germany | The Revolutions of 1848

Now the German revolutions in 1848 roughly paralleled those in Italy. In Germany, too, liberalism and nationalism won initial victories and then collapsed before internal dissension and Austrian resistance.

-

Italy | The Revolutions of 1848

In Italy new reform movements supplanted the discredited Carbonari. By the 1840s three movements were competing for the leadership of Italian nationalism. Two were moderate. One of these groups, based in the north, favored the domination of Piedmont; its leader, Count Camillo Cavour (1810-1861), was an admirer of British and French liberalism.

-

France | The Revolutions of 1848

The economic crisis hit France with particular severity. Railroad construction almost ceased, throwing more than half a million out of work; coal mines and iron foundries, in turn, laid off workers.

-

The Revolutions of 1848 | Romanticism, Reaction, and Revolution

Nationalism was a common denominator of several revolutions in 1848. It prompted the disunited Germans and Italians to attempt political unification, and it inspired the subject peoples of the Habsburg Empire to seek political and cultural autonomy. The new nationalism tended to focus on language.

-

The Lessons of 1830 | The Revolutions of 1830

The revolutionary wave of the 1830s confirmed two major political developments. First, it widened the split between the West and the East already evident after the revolutions of 1820. Britain and France were committed to support cautiously liberal constitutional monarchies both at home and in Belgium. On the other hand, Russia, Austria, and Prussia were…

-

Failure in Poland, Italy, and Germany | The Revolutions of 1830

The course of revolution in Poland contrasted tragically with that in Belgium. In 1815 the kingdom of Poland had the most liberal constitution on the Continent; twenty years later it had become a dependency of the Russian Empire.

-

Success in Belgium | The Revolutions of 1830

The union of Belgium and the Netherlands, decreed by the peacemakers of 1815, worked well only in economics. The commerce and colonies of Holland supplied raw materials and markets for the textile, glass, and other manufactures of Belgium.

-

Success in France | The Revolutions of 1830

The ambiguities of Louis XVIII’s policies were most evident in the constitutional charter that he issued in 1814. Some sections sounded like the absolute monarchy of Louis XIV; for example, the preamble asserted the royal prerogative: “The authority in France resides in the person of the king.” But the charter also granted a measure of…

-

The Revolutions of 1830 | Romanticism, Reaction, and Revolution

The next revolutionary wave, that of 1830, swept first over France. King Louis XVIII (r. 1814-1824) would have preferred to be an absolute ruler, but he knew that returning to the Old Regime was impractical, especially since he was declining in health and suffered from the additional political handicap of having been imposed on the…

-

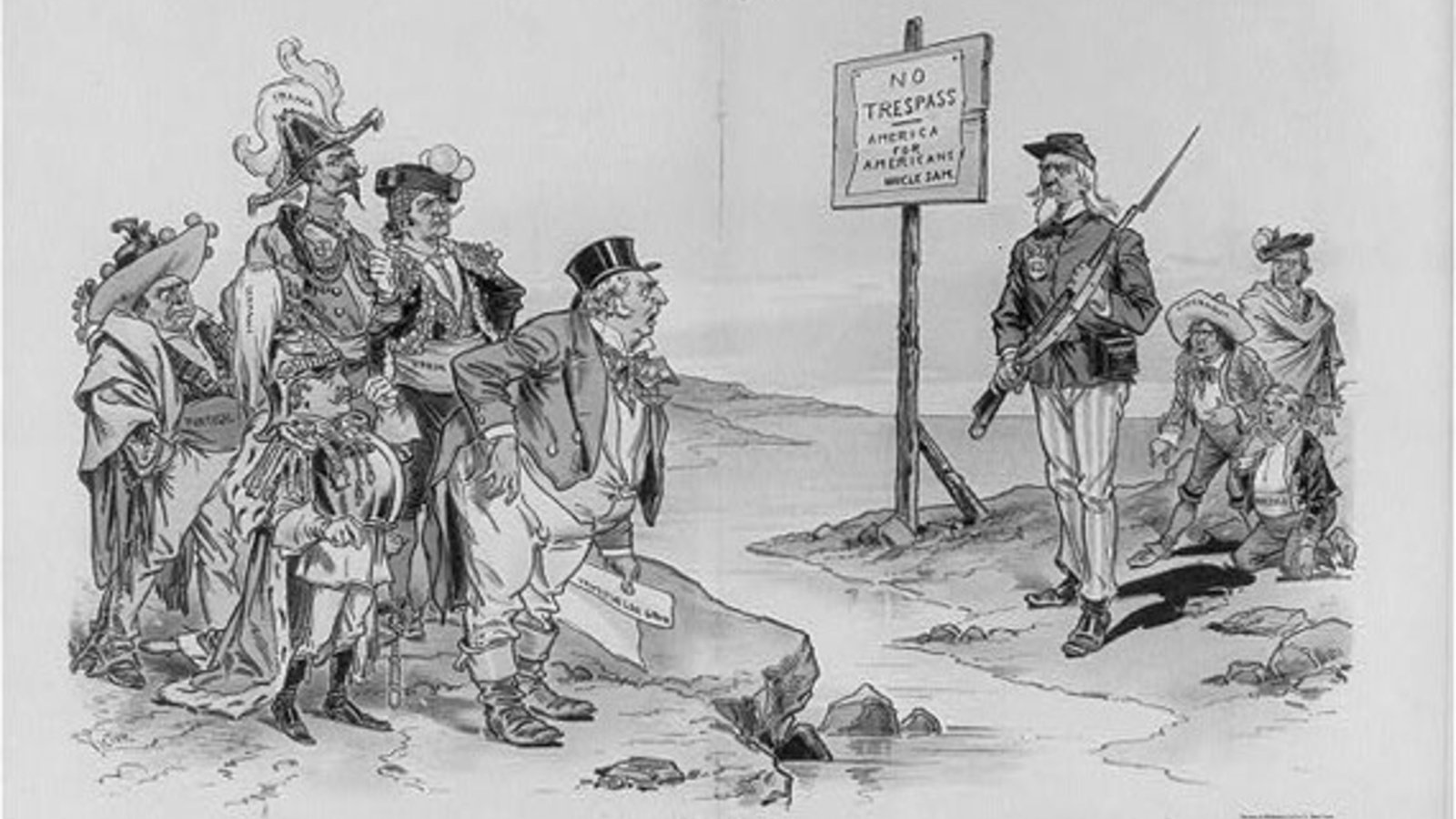

The Monroe Doctrine

In foreign relations, the United States sought to isolate itself as best it could from the contamination of European wars. Clearly those wars would spread to the New World if the European powers acquired new colonies in the Western Hemisphere. President James Monroe addressed this point in 1823 in what came to be known as…

-

The Decembrist Revolt in Russia, 1825 | Romanticism, Reaction, and Revolution

Russia, which did so much to determine the outcome of revolutions elsewhere, itself felt the revolutionary wave, but with diminished force. Liberal ideas continued to penetrate the country, spread by the secret societies that flourished in Russia after 1815.

-

Serbian and Greek Independence, 1804-1829 | Romanticism, Reaction, and Revolution

The Greek revolt was part of the general movement of the Balkan nations for emancipation from their Turkish overlords. During the last quarter of the eighteenth century many peoples of the Balkan peninsula were awakening to a sense of national identity under the impact of French revolutionary and romantic ideas. They examined their national past…

-

The Persistence of Revolution, 1820-1823 | Romanticism, Reaction, and Revolution

The revolutionary leaders of the post-Napoleonic generation remained firm for liberty, equality, and fraternity. The first two words of the great revolutionary motto continued to signify the abolition of noble and clerical privileges in society and, with few exceptions, laissez-faire economics. They also involved broadening civil rights, instituting representative assemblies, and granting constitutions, which would…

-

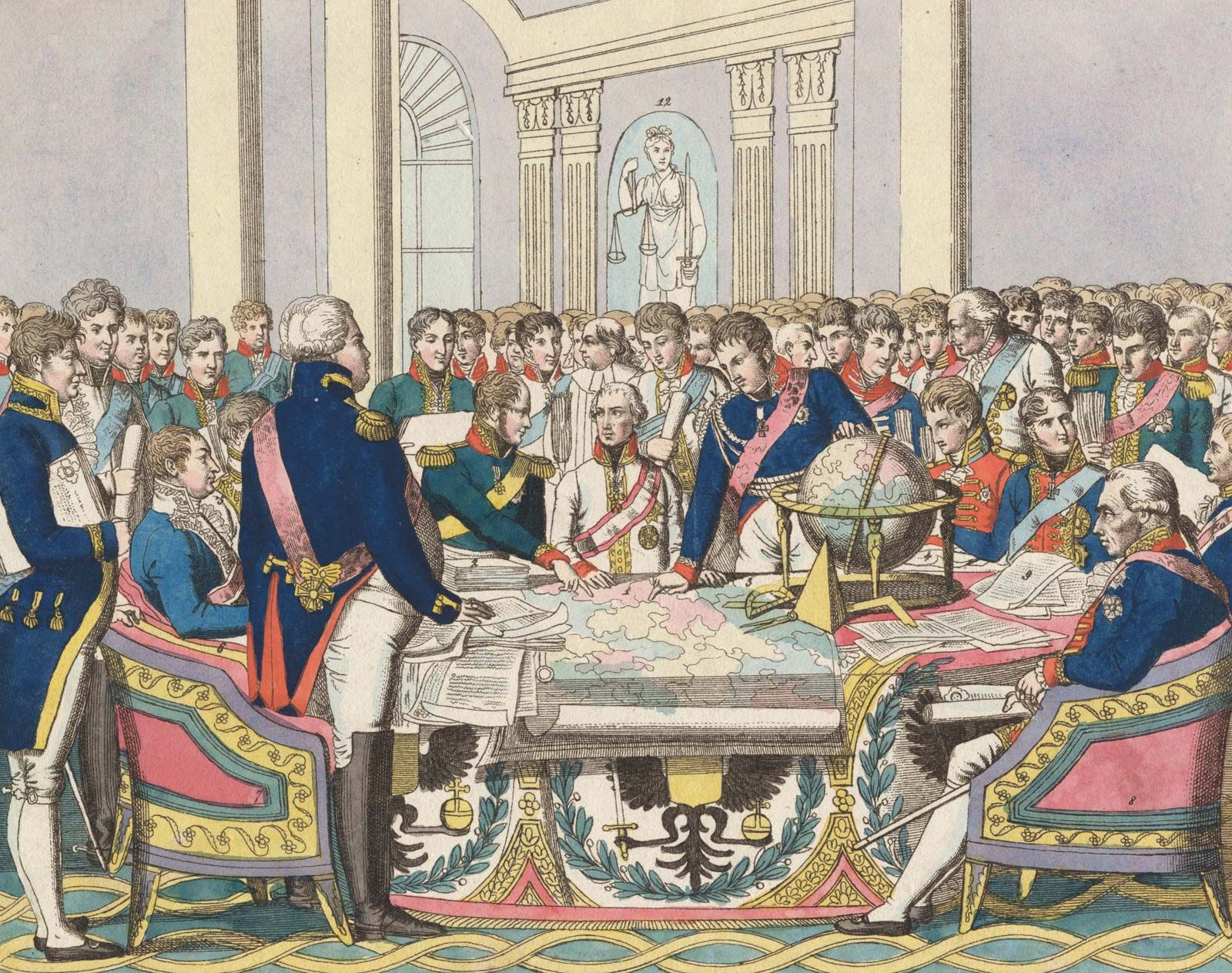

The Congress of Vienna, 1814-1815 | Romanticism, Reaction, and Revolution

In 1814 and 1815 Metternich was host to the Congress of Vienna, which approached its task of rebuilding Europe with conservative deliberateness. For the larger part of a year, the diplomats indulged in balls and banquets, concerts and hunting parties. “The Congress dances,” quipped an observer, “but it does not march.” Actually, the brilliant social…

-

The Reconstitution of a European Order | Romanticism, Reaction, and Revolution

The romantic movement was too intellectually scattered to provide a blueprint for the reconstruction of Europe after the defeat of Napoleon. The general guidelines for reconstruction were to be found in the writings of the English orator Edmund Burke (1729-1797), who set the tone for counterrevolutionary conservatism.

-

The Romantic Style | Romanticism, Reaction, and Revolution

The style of romanticism was not totally at variance with that of the Enlightenment; not only a modified doctrine of progress but also the cosmopolitanism of the eighteenth century lived on into the nineteenth. Homer, Cervantes, Shakespeare, and Scott had appreciative readers in many countries; giants of the age such as Beethoven and Goethe were…

-

Religion and Philosophy and The Romantic Period | Romanticism, Reaction, and Revolution

The romantic religious revival was marked at the institutional level by the pope’s reestablishment in 1814 of the Jesuit order, whose suppression in 1773 had been viewed as one of the great victories of the Enlightenment. Catholicism gained many converts among romantic writers, particularly in Germany, and the Protestants also made gains.

-

The Arts and The Romantic Period | Romanticism, Reaction, and Revolution

The virtual dictator of European painting during the first two decades of the nineteenth century was the French neoclassicist Jacques Louis David (1748-1825). David became a baron and court painter under Napoleon, then was exiled by the restored Bourbons. No matter how revolutionary the subject, David employed traditional neoclassical techniques, stressing form, line, and perspective.

-

Music and The Romantic Period | Romanticism, Reaction, and Revolution

Romantic musicians, like romantic poets, sought out the popular ballads and tales of the national past; they also sought to free their compositions from classical rules. Composers of opera and song turned to literature: Shakespeare’s plays, Scott’s novels, Byron’s poetry, and the poems and tales of Goethe and Pushkin.

-

The Return to the Past | Romanticism, Reaction, and Revolution

The romantics’ enthusiasm for the Middle Ages in general and for the earlier history of their own nations in particular linked the universal (nature) to the particular (the nation-state). Nationalism was an emotional, almost mystical force. The romantic return to the national past, though intensified by French expansionism, had begun before 1789 as part of…

-

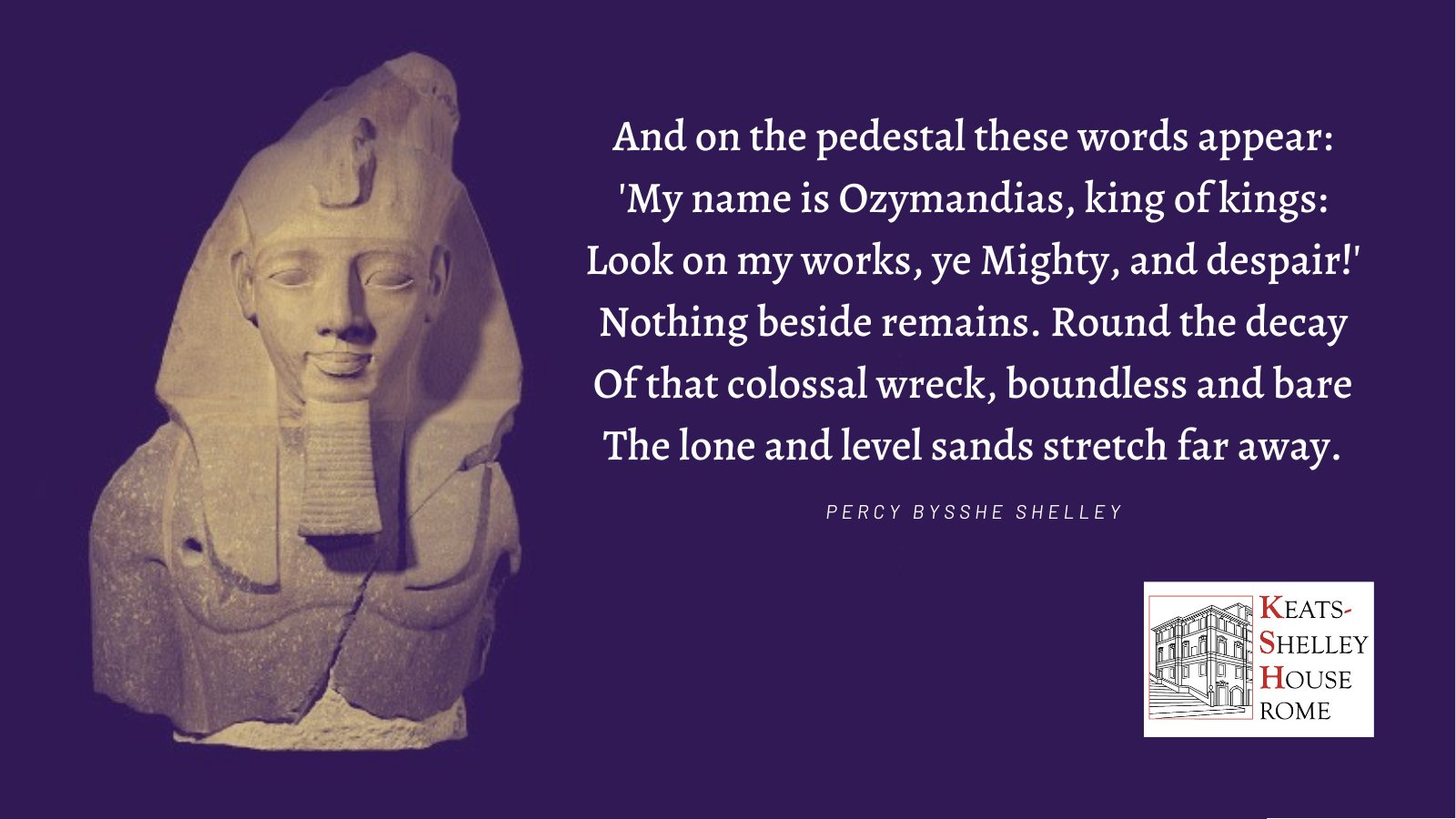

Shelley on the Decay of Kings

In 1817 the English poet Percy Bysshe Shelley captured the romantic sense of despair in his poem “Ozymandias,” which stated anew the biblical warning that the overweening aspirations of arrogant humanity would be as dust to dust. I met a traveler from an antique land Who said “Two vast and trunkless legs of stone Stand…

-

An Age of Feeling and Poetry, 1790-1830 | Romanticism, Reaction, and Revolution

Romanticism is best revealed through literature. Literary romanticism may be traced back to the mid-eighteenth century—to novels of “sensibility” like Rousseau’s La Nouvelle Héloïse and to the sentimental “tearful comedies” of the French stage. In the 1770s and 1780s a new intensity appeared in the very popular works of the German Sturm and Drang, for…

-

The Romantic Protest | Romanticism, Reaction, and Revolution

The romantic period (usually dated 1780 to 1830) was one in which political and cultural thought showed such a varied concern for tradition that many historians dispute that there was sufficient unity of thought to refer to a “movement” at all. Moreover, writers of “the romantic school” in Germany were quite different from writers in…

-

Romanticism, Reaction, and Revolution

The origins of the Modern West lay in the French Revolution, and the rising nationalism stimulated by it and by the conquests of Napoleon. They lay also in the developments of the short, intense period between the Congress of Vienna and the wave of revolutions that moved across Europe in 1848. During this time and…

-

Summary | The French Revolution and Napoleon

Years of fiscal mismanagement contributed to the severe financial crisis that precipitated the French Revolution. Louis XVI, irresolute and stubborn, was unable to meet the overwhelming need for reform. The third estate, which constituted over 97 percent of the population, held some land, but rural poverty was widespread.

-

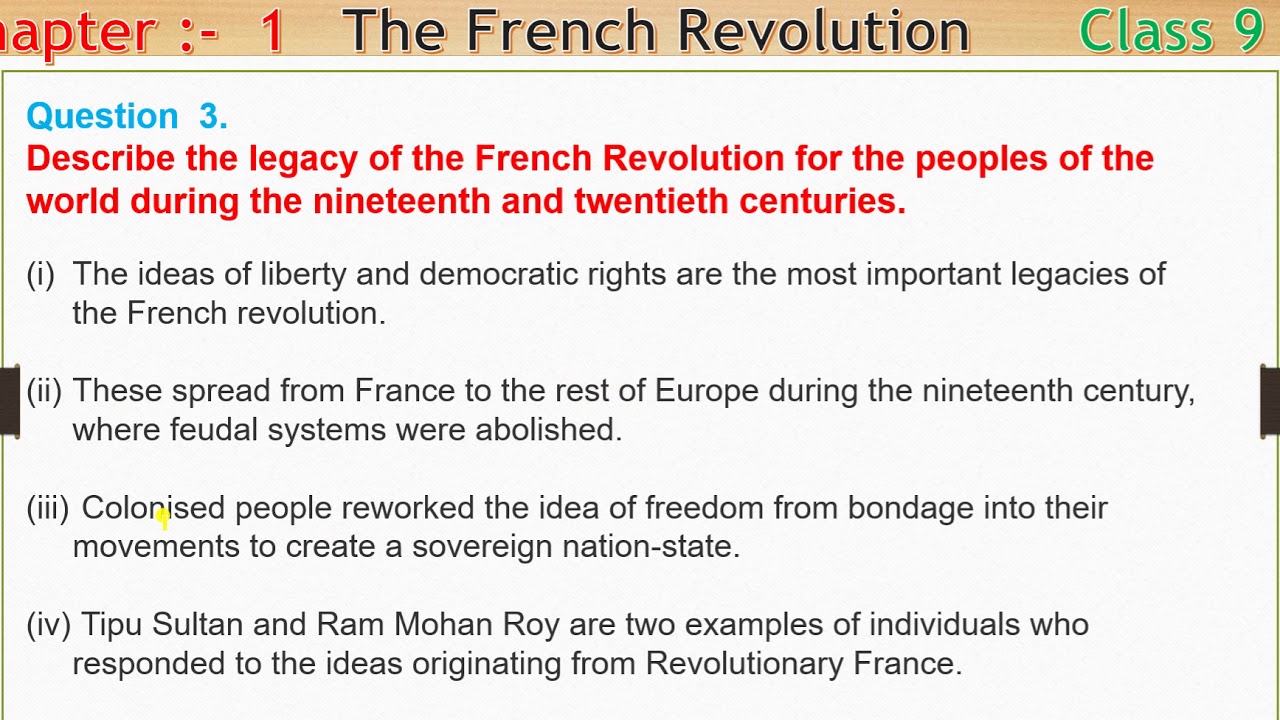

The Legacy of the Revolution | The French Revolution

The French Revolution was the most fundamental event of the nineteenth century, and its meaning, its causes, and its impact continue to be debated. One debate is whether there was an autonomous peasant revolution directed against feudalism imbedded within the larger revolution, with the peasants seeking their own road to capitalism. Clearly hostility to harvest…

-

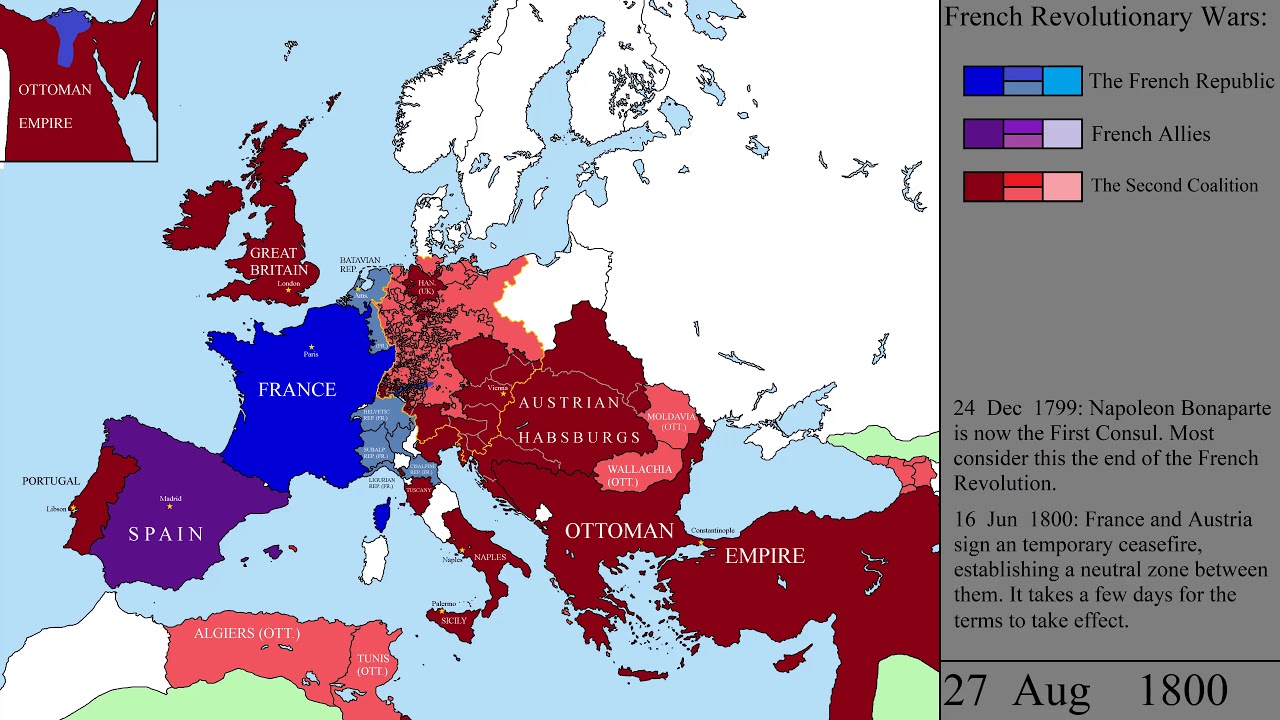

Napoleon’s Fall, 1813-1815 | Napoleon and Europe

The British had been the first to resist Napoleon successfully, at Trafalgar and on the economic battlefields of the Continental System. Then had come Spanish resistance, followed by Russian. Now in 1813 almost every nation in Europe joined the final coalition against the French. Napoleon raised a new army, but he could not so readily…

-

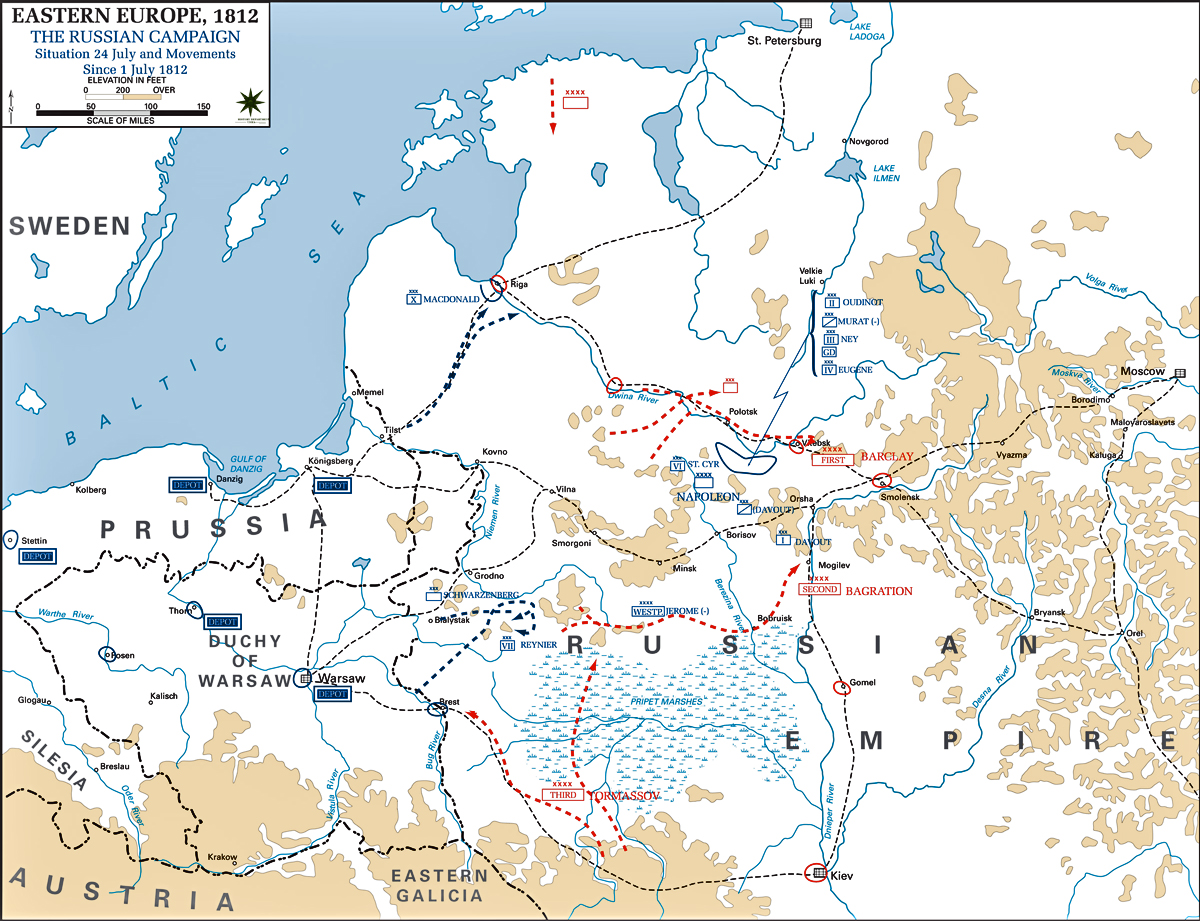

The Russian Campaign, 1812-1813 | Napoleon and Europe

The event that defeated Napoleon’s great designs was the French debacle in Russia. French actions after 1807 soon convinced Czar Alexander that Napoleon was not keeping the Tilsit bargain and was intruding on Russia’s sphere in eastern Europe.

-

German National Awakening | Napoleon and Europe

German intellectuals launched a campaign to check the great influence that the French language and French culture had gained over their divided lands.

-

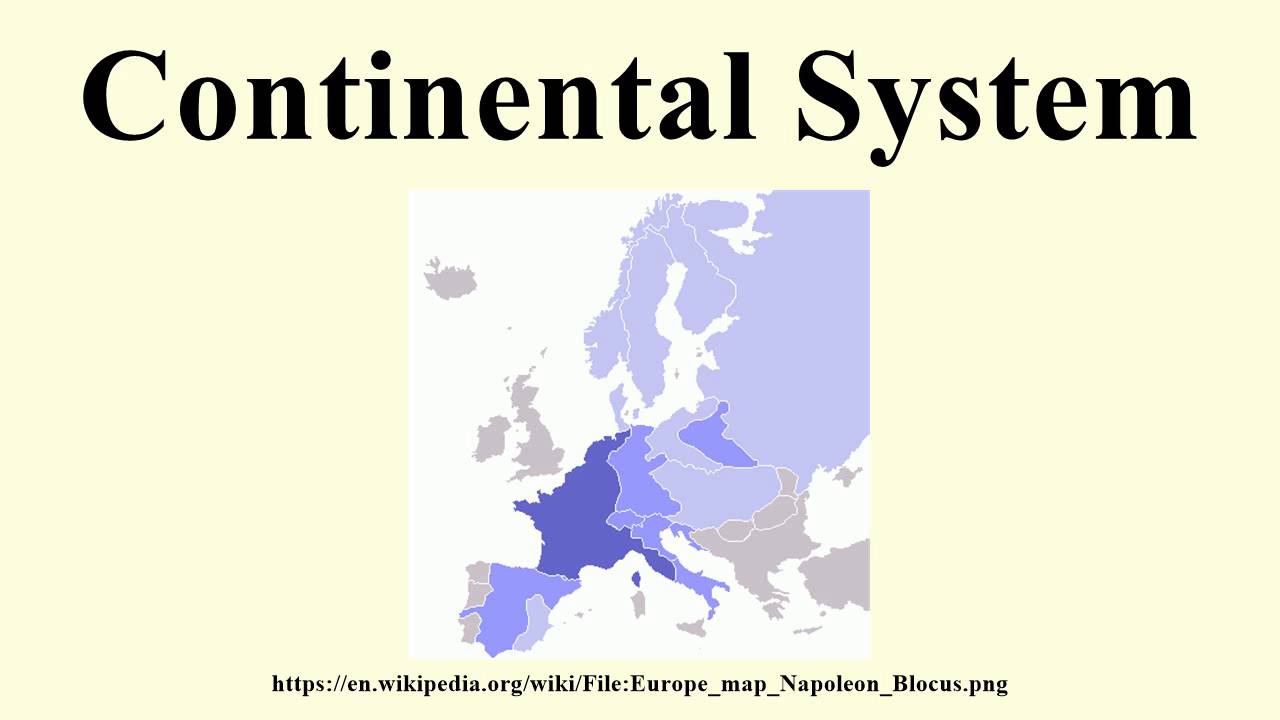

The Peninsular War, 1808-1813 | Napoleon and Europe

In Europe the political and military consequences of the Continental System formed a decisive and disastrous chapter in Napoleonic history, a chapter that opened in 1807 when the emperor decided to impose the system on Britain’s traditional ally, Portugal. The Portuguese expedition furnished Napoleon with an excuse for the military occupation of neighboring Spain. In…

-

The Continental System | Napoleon and Europe

Nowhere was Napoleon’s imperialism more evident than in the Continental System. This was an attempt to regulate the economy of the whole Continent. It had a double aim: to build up the export trade of France and to cripple that of Britain.

-

Napoleon Rallies His Troops

In the Italian campaign Major General Bonaparte, still only in his twenties, cleared the Austrians out of their strongholds in one year and made them sue for peace. He showed a remarkable ability to strike quickly and to surprise his opponents before they could consolidate their defenses. He also showed a gift for propaganda and…

-

The War, 1800-1807 | Napoleon and Europe

Napoleon had barely launched the Consulate when he took to the field again. The second coalition was falling to pieces. Czar Paul of Russia alarmed Britain and Austria by his interest in Italy, and Britain offended him by retaining Malta, the headquarters of his Knights. Accordingly, the czar formed a Baltic League of Armed Neutrality…

-

Napoleon and Europe

To many in France, Napoleon was and remains the most brilliant ruler in French history. To many Europeans, on the other hand, Napoleon was a foreigner who imposed French control and French reforms. Napoleonic France succeeded in building up a vast and generally stable empire, but only at the cost of arousing the enmity of…

A History of Civilization