In 1556 Charles V abdicated both his Spanish and imperial crowns and retired to a monastery, where he died two years later. His brother, who became Emperor Ferdinand I (r. 1556-1564), secured the Austrian Habsburg territories; his son, Philip II of Spain (r. 1556— 1598), added the Spanish lands overseas (Mexico, Peru, and in the Caribbean), the Burgundian inheritance of the Netherlands, and Milan and Naples in Italy.

Even without Germany, Philip’s realm was a supranational state, drawing much gold and silver from the New World and threatening France, England, and the whole balance of power. Aware of the potential of such power, contemporary Italians were saying that “God has turned into a Spaniard.”

Like his father, Philip II found Protestantism intolerable. His attempt to invade England and restore Catholicism would make him one of the villains of Anglo- Saxon and Protestant tradition. In fact, he was no lover of war for its own sake, but was a serious, hard-working administrator who was both the most powerful monarch and the greatest civil servant of the age.

Charles V had come to count heavily on the wealth of the Netherlands to finance his constant wars. But he joined into a unified state the seventeen provinces of the Netherlands, which were jealous of their traditional autonomy. Each province had its own medieval Estates or assembly, dominated by the nobility and wealthy merchants, which raised taxes and armies. In the midsixteenth century the area was still overwhelmingly Catholic.

Whereas Charles V had liked the Netherlands, Philip II was thoroughly Spanish in outlook. Not only Philip’s temperament antagonized his subjects in the Low Countries, but also his ideas about centralized efficient rule, which led him to curtail their political and economic privileges. The inhabitants were intent on conducting business without the restrictions imposed on trade and industry by Spanish regulations. The Protestants among them resented and feared Philip’s use of the Inquisition in the Netherlands.

Philip sent Spanish garrisons to the Netherlands and attempted to enforce edicts against heretics. Opposition, which centered at first in the privileged classes, soon spread downward. In 1566, when two hundred nobles petitioned Philip’s regent to adopt a more moderate policy, an official sneeringly referred to “these beggars.” The name stuck and was proudly adopted by the rebels. The political restlessness, combined with an economic slump and the growing success of the Calvinists in winning converts, touched off riots in August 1566 that resulted in severe destruction of Catholic churches in Ghent, Antwerp, and Amsterdam.

Philip responded by dispatching to the Netherlands an army of ten thousand Spaniards headed by the unyielding, politically clumsy duke of Alva. Alva set up a Council of Troubles—later dubbed the Council of Blood— which resorted to large-scale executions, confiscations, and fines. The number of victims executed under the Council of Blood totaled about fifteen hundred, yet repression only heightened the opposition to Spanish policy. In 1573 Alva was recalled to Spain.

Meantime, the rebel “Beggars” turned to naval guerrilla warfare, gaining control of the ports of the populous northern province of Holland, which became a refuge for Protestants from other provinces. A split was developing between a largely Catholic south and a mainly Protestant north—to use modern terminology, between Belgium and Holland. North and south had much to unite them, and union of all seventeen provinces was the goal of the rebel leader, Prince William of Orange.

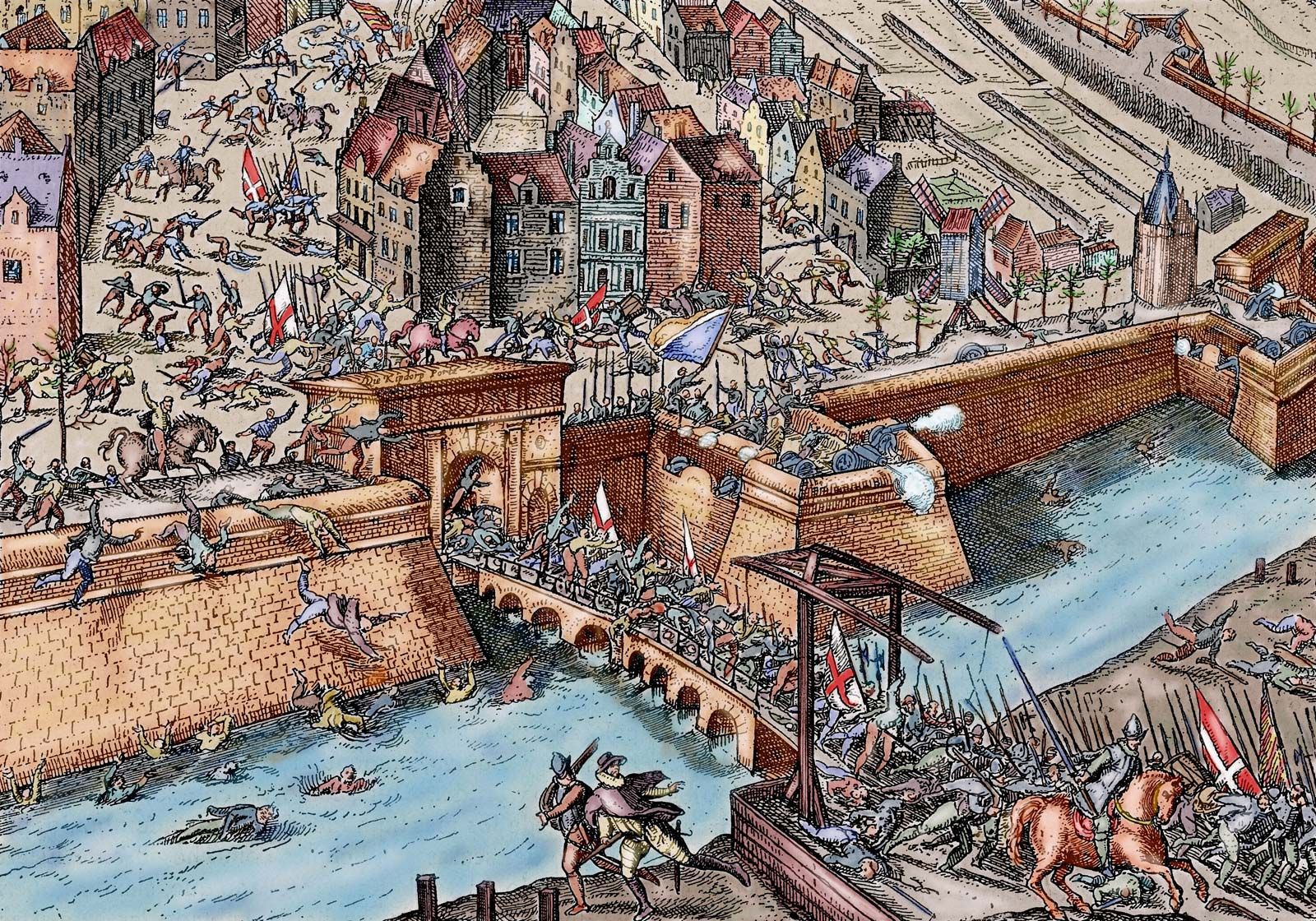

William’s goal of unification seemed almost assured in the wake of widespread revulsion at the “Spanish Fury” of 1576, when Spanish troops sacked Antwerp and massacred several thousand inhabitants. But in 1578, when the duke of Parma arrived to govern the Netherlands, Philip at last appeared willing to compromise. The cost of the war was becoming intolerable, and Spanish executions had made the Dutch resolve to fight to the last man. By restoring old privileges of self-rule, Parma won back the ten southern provinces, which remained largely Catholic; it was too late to win back the northern provinces.

In 1581 the Dutch took the decisive step of declaring themselves independent of the Spanish Crown. They made good that declaration by courageous use of their now much better-organized land forces. Moreover, Philip faced grave internal economic problems just when he was being drawn into fighting on other fronts. He had to cope with the Turks, the French Protestants, and the anti-Spanish moderate wing of French Catholics. In 1585 the English queen, Elizabeth I, came out on the side of the Dutch and sent an army to their aid.

The great armada of unwieldy men-of-war that Philip sent out to invade England was defeated in the English Channel in July 1588 by a skillfully deployed lighter English fleet and was further battered afterward by a great storm. This battle was the beginning of the end of Spanish preponderance, the start of English greatness in international politics, and the decisive step toward Dutch independence. These portentous results were not as evident in 1588 as they became later, but even at the time the defeat of the Spanish Armada was viewed as a great event, and the storm that finished its destruction was christened the “Protestant wind.”

In 1598 Philip II died. Save for the seven northern provinces of the Netherlands, the great possessions that had been his when he began his reign were intact. In 1580 he had added Portugal by conquest and brought the whole Iberian peninsula under a single rule. Yet after over forty years of rule he had left his kingdom worn out, drained of men and money, only sluggishly able to attend to the needs of a vast empire.