While the industrial powers of Europe were expanding overseas, the United States acquired by purchase and conquest the remainder of its Manifest Destiny—a dominion from sea to sea that was “to bring the blessings of liberty” to the entire continent. The United States believed it had a moral obligation to expand in order to extend the area of freedom against monarchical or dictatorial governments.

The first American empire was solely within the continent. By the end of the century the Native American had been swept aside into reservations and was a ward of the state. Once the Native Americans were “pacified”— the last major battle was fought at Wounded Knee in Dakota Territory, in December 1890—and the frontier was thought to be closed, the main thrust of the westward movement was over, and Americans would have to look elsewhere for new worlds to conquer.

By the 1870s a national consensus was emerging that the new frontiers should be sought overseas, particularly in the Caribbean and the Pacific. Control of the harbors of San Diego, San Francisco, and the Juan de Fuca Strait (near present-day Seattle) was a primary aim. Such needs strengthened the desire of American statesmen to find a peaceful solution to their controversy with the British over the Oregon Territory (1846); and the acquisition of California in 1848 was seen as essential to American advancement into the Pacific.

In 1854 Admiral Perry persuaded the Japanese to open two ports to American vessels by the Treaty of Kanagawa. But if the China trade and the expected Japan trade were to flourish, American vessels needed repair and refueling facilities elsewhere in the Pacific. The Hawaiian Islands now took on added significance, for, besides refuge, they also afforded supplies of sandalwood for the China trade. After the discovery of gold in California in 1848, the islands provided the mainland with badly needed sugar and foodstuffs.

In 1875 the sugar growers in Hawaii, largely Americans, obtained a reciprocal trading agreement with the United States that stipulated that no part of Hawaii might be given by the Hawaiian Kingdom to any other country. Sugar exports to America increased, until the islands were utterly dependent upon the continental market, and in 1884, when the agreement was renewed, the United States was granted exclusive use of Pearl Harbor as a naval base. In the meantime, the indigenous population declined rapidly, and the planters, in need of labor, imported thousands of Chinese, Japanese, and Portuguese. Hawaii was annexed on July 7,1898, the first land outside the North American continent to fly the American flag on a permanent basis.

As early as 1823 the Monroe Doctrine had made it clear that the United States saw itself as exerting a strong moral influence in Latin America. The Monroe Doctrine was given a corollary in 1895, when President Grover Cleveland (1837-1908) intervened in a boundary controversy between Venezuela and Britain, asserting that the United States had an obligation to the free nations of the entire Western Hemisphere to protect them from abuse by European powers.

In the same year Cuba revolted against Spain. As the revolt spread, American sugar and tobacco growers and iron mine owners on the island complained of the destruction of their property. Outnumbered by the Spanish troops in Cuba, the revolutionaries turned to guerrilla warfare, hoping to draw the United States into intervening. A new governor, appointed in 1896, sought to limit the effects of guerrilla tactics by forcing large elements of the rural population into concentration camps. There thousands died. While American business opposed direct intervention in so unstable a situation, the “yellow” press printed atrocity stories that stirred up prorevolutionary sympathy. Then, on February 15,1898, the U.S. battleship Maine, at anchor in Havana harbor, was destroyed by an explosion that killed 260 officers and men.

President William McKinley (1843-1901) sent an ultimatum to Spain demanding an armistice in the revolution and an end to the concentration camps. Spain revoked the camp policy at once, and instructions were sent to the governor ordering an armistice. But without waiting to learn the details of the Spanish armistice order, McKinley presented the Cuban crisis to Congress with the charge that Spain’s response had been “disappointing.”

After lengthy debate, Congress voted recognition of Cuban independence on April 19, authorized the use of American troops to make recognition effective, and pledged “to leave the government and control of the Island to its people.” McKinley signed the resolution, and the United States served an ultimatum upon Spain to grant Cuban independence. Spain broke diplomatic relations; the American navy blockaded Cuban ports; Spain declared war against the United States; and the United States countered with a declaration of war against Spain.

The Spanish-American War lasted 115 days, and the American forces swept all before them. The Spanish empire was broken, its army crushed, and virtually all of its battle fleet sunk or driven onto the beaches. Five days after war was declared, Admiral George Dewey (18371917), forewarned two months earlier by Theodore Roosevelt, then assistant secretary of the navy, to sail for Hong Kong, reached Manila Bay. There he methodically destroyed a larger Spanish fleet, and thirteen days later American troops, reinforced by Filipino guerrillas under General Emilio Aguinaldo (1869-1964), occupied Manila.

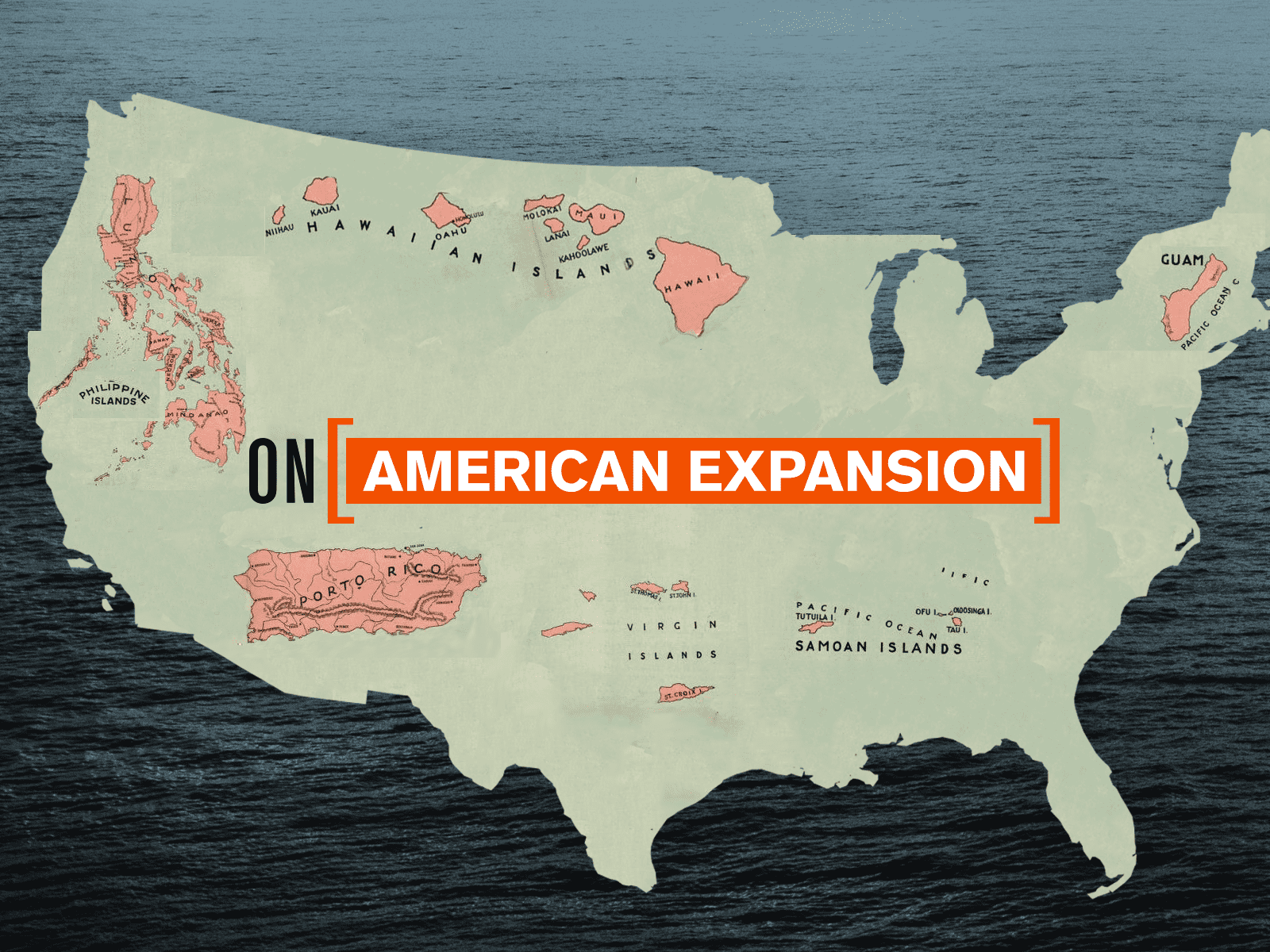

The Treaty of Paris, by which the Philippines were ceded to the United States, was signed on December 10. Spain surrendered all claim to Cuba, assumed the Cuban debt, ceded Puerto Rico and the Pacific island of Guam to the United States as indemnity, and received $20 million in payment for the Philippines. In one quick step the United States had become a maritime empire with interests in both the Caribbean and the Far East.

American troops remained in control of Cuba until 1902. In effect, Cuba became an American protectorate and the second largest recipient of American investments in the Western Hemisphere. Investment required stability, and from 1917 until 1934, the American government made it clear that it would recognize no hostile regime in Cuba.

The Pacific continued to be the testing ground for the growth of an American empire, however. To maintain control over Caribbean areas seemed natural, for Americans had long considered themselves to be the guardian of the New World. To attempt the same in the remote Pacific invited new dangers. The Filipinos felt betrayed by the continued presence of the American army, and when Aguinaldo learned that the Treaty of Paris had given the Philippines to the United States, he organized an armed revolt that continued as guerrilla warfare until mid-1902.

A special commission established by President McKinley recommended ultimate independence for the islands, with American rule to continue indefinitely until the Filipinos proved themselves “ready for self- government.” One condition of such proof was to terminate the rebellion and accept American rule. In 1916 partial home rule was granted to the Philippines; in 1935 the islands became a commonwealth; and in 1946 they were granted full independence.

On the whole, American imperialism in Asia was nonterritorial, since the British naval presence in the area made outright colonial expansion by the United States difficult and in most cases unnecessary. American policy was best symbolized by the Open Door concept. The Opium War of 1841 between Britain and China, the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), and the disintegration of the Manchu Empire in the 1890s had left the Chinese open to demands by European nations for political and economic concessions and the carving up of the China trade into spheres of influence.

The British had taken Hong Kong, and the French, Germans, and Russians were on the move. The British suggested that the United States join in guaranteeing equality of commercial access to China for all Western nations. In a circular letter of September 6,1899, Secretary of State John Hay (1838-1905) asked for assurances from Germany, Russia, and Britain (and later from France, Italy, and Japan as well) that none would interfere with any treaty ports in China and that none would discriminate in favor of their own subjects when collecting railroad charges and harbor dues. Although he received evasive replies, Hay announced in March 1900 that the principle of the Open Door was “final and definitive.”

The Panama Canal Zone added a third and final chapter to the American attempt to compromise between economic advantage and political interest. Concluding that intervention in the Caribbean and Central America would continue to be necessary to the United States, Theodore Roosevelt moved forward on two fronts. Roosevelt saw the election of 1900 as a mandate on imperialism. Desiring canal rights in Central America, he encouraged a Panamanian revolt against Colombia, immediately recognized the independence of Panama, and in November 1903, with the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty, gained perpetual rights of use and control of a canal zone across the isthmus of Panama for the United States, in exchange for $10 million and an annual fee.

A year later “TR” added a further corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, fearing armed European intervention in Venezuela after that nation had defaulted on debts to Britain and Germany. Roosevelt stated that if Latin American nations could not administer their own financial affairs, and if they gave European nations cause for intervention, then the United States might be forced to “exercise . . .

an international police power” in the Western Hemisphere. This was especially applicable to nations that could threaten access to the canal route, and when the Panama Canal was opened on August 15, 1914, the United States had further reason to protect its Caribbean approaches. Under Roosevelt’s corollary, Santo Domingo became an American protectorate in 1907, as did Haiti in 1915.

American marines were stationed in Nicaragua from 1912 until 1925; in 1916 the United States acquired the right to construct a canal across Nicaragua; and the Virgin Islands were purchased from Denmark in 1917. Even revolution in Mexico—which began in 1913 and led to American intervention at Vera Cruz in 1914 and along the northern border two years later—did not disturb the flow of commerce, investment, and shipping in the Caribbean, which had become “an American lake.”