Quite as clear, though still the subject of complex debate among Americans, was the emergence of the United States as a great international power. From the very beginning it had a department of state and a traditional apparatus of ministers, consuls, and, later, ambassadors.

By the Monroe Doctrine of the 1820s it took the firm position that European powers were not to extend further their existing territories in the Western hemisphere. This was an active expression of American claims to a far wider sphere of influence than the continental United States.

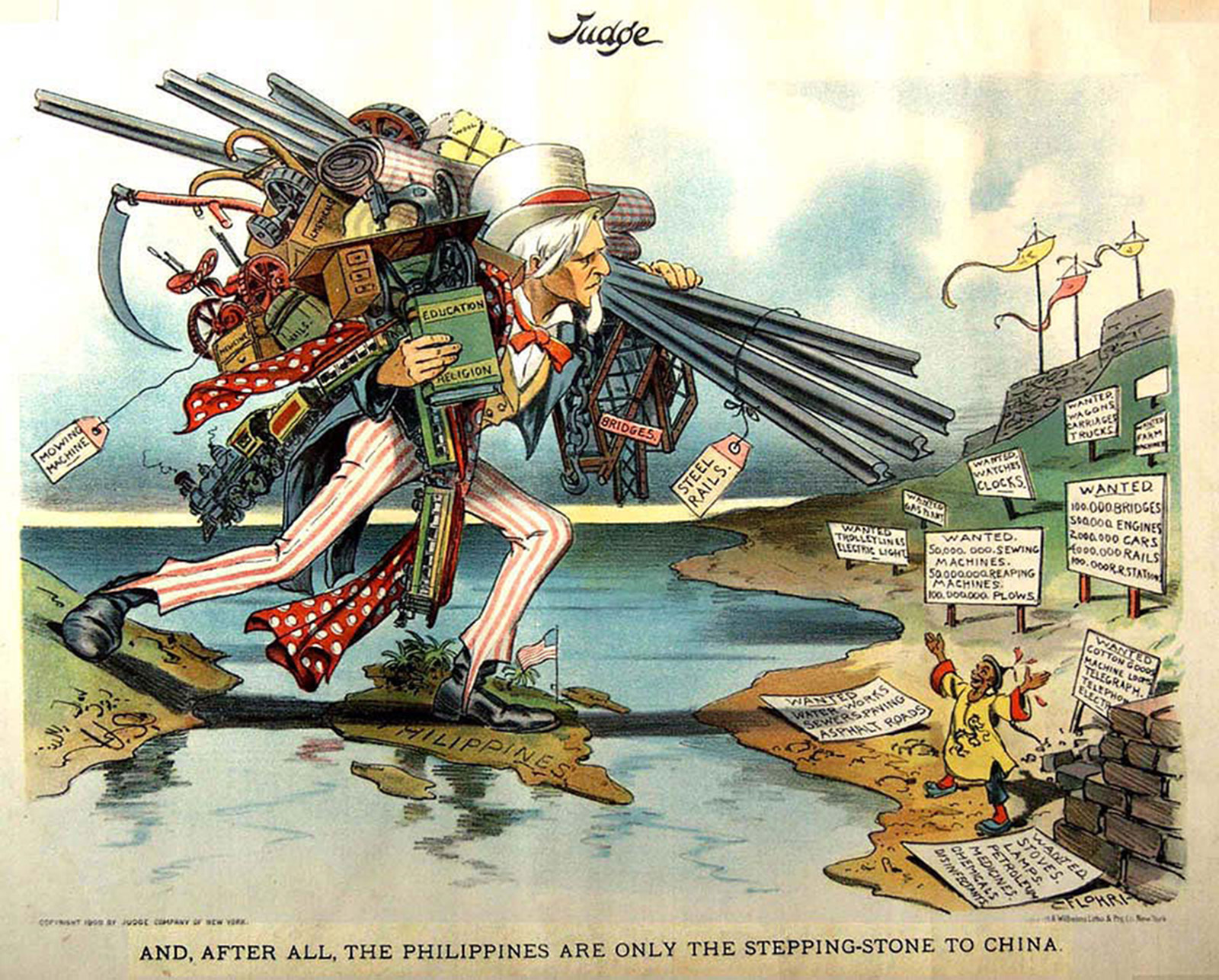

Although Americans took no direct part in the nineteenth-century balance-of-power politics in Europe, they showed an increasing concern with a balance of power in the Far East, where they had long traded and wanted an “Open Door” to commerce. As a result of a brief war in 1898 with Spain that broke out in Cuba, the United States annexed the Philippine Islands and Puerto Rico from Spain. The newly “independent” Cuba became a veiled American protectorate, and in 1900 Hawaii became a territory of the United States (see Chapter 22). All this seemed to many to constitute an American empire.

Theodore Roosevelt, who owed his rapid political rise partly to his military exploits in the Spanish-American War, was a vigorous expansionist. He pressed the building of the Panama Canal, which opened in 1914, stretched the Monroe Doctrine to justify American military intervention in Latin American republics, upheld the Far Eastern interests of the United States, and advocated a larger navy. Roosevelt wanted to see his country play an active part in world affairs, as exemplified by his arbitrating the peace settlement between Russia and Japan in 1905.

After over a century of expanding wealth and trade, the United States had come to take full part in international commercial relations. Except when the federal government was blockading the Confederacy, it had stood firmly for rights to trade. This fact alone might have brought the United States into the world war of 1914-1918, as it had brought it previously into the world war of 1792-1815.

But in 1917 America was an active participant in the world state system, even though it had avoided any formal, permanent entangling alliances. The great themes of modern European history—industrialization, modernization, national unity and nationalism, imperialism, intellectual ferment—were all so evident that Americans could not question that they were part of the broad stream of history.