Immediately after the Russo-Japanese War the future Kadets held banquets throughout Russia to adopt a series of resolutions for presentation to a kind of national congress of zemstvo representatives.

Although the congress was not allowed to meet publicly, its program—a constitution, basic civil liberties, class and minority equality, and extension of zemstvo responsibilities—became widely known and approved. The czar issued a statement so vague that all hope for change was dimmed, and took measures to limit free discussion.

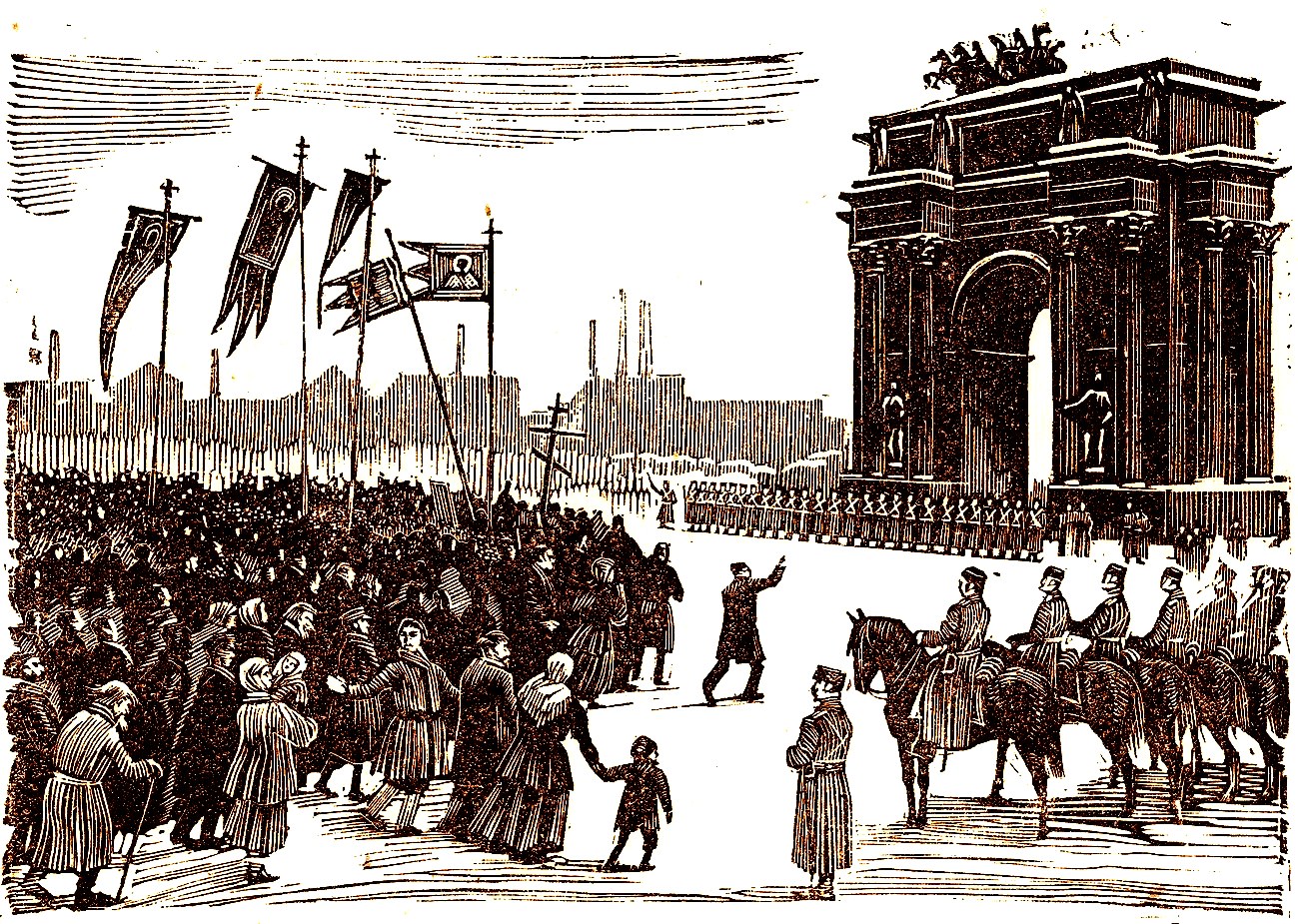

Ironically, it was a police agent of the government who struck the fatal spark. He had been planted in the St. Petersburg iron works to combat SD efforts to organize the workers, and to substitute his own union. He organized a parade of workers to demonstrate peacefully and to petition the czar directly for an eight-hour day, a national assembly, civil liberties, the right to strike, and other moderate demands.

When the workers tried to deliver the petition, Nicholas left town. Troops fired on the peaceful demonstrators, some of whom were carrying portraits of the czar to demonstrate their loyalty. Hundreds of workers were killed on “Bloody Sunday” (January 22, 1905).* The massacre made revolutionaries of the urban workers, and the increasingly desperate moderate opposition joined with the radical opposition.

Amid mounting excitement, the government at first seemed to favor the calling of a zemski sobor—consultative not legislative, but still a national assembly of sorts. But while the czar hesitated, demonstrations occurred throughout the summer of 1905. In October the printers struck. No newspapers appeared, and the printers, with SD aid, formed the first soviet, or workers’ council. When the railroad workers joined the strike, communications were cut off between Moscow and St. Petersburg. Soviets multiplied and relations between the czar and his subjects collapsed.

The Bolsheviks saw the soviet as an instrument for the establishment of a provisional government, for the proclamation of a democratic republic, and for the summoning of a constituent assembly. This program differed relatively little from the program of the moderate liberals, who originally had hoped to keep the monarchy and obtain their ends by pressure rather than by violence.

At the time, the Bolsheviks, like other Marxists, accepted the view that it was necessary for Russia to pass through a stage of bourgeois democracy before the time for the proletarian revolution could come. They were therefore eager to help along the bourgeois revolution.

Nicholas was faced, as Witte told him, with the alternatives of either imposing a military dictatorship or summoning a truly legislative assembly with veto power over the laws. The czar finally chose the latter course, and in October 1905 he issued a manifesto that promised full civil liberties at once, and a legislative assembly or duma to be elected by universal suffrage. In effect, this October Manifesto ended the autocracy, since the duma was to be superior to the czar in legislation.

Yet the October Manifesto did not meet with universal approval. On the right, a government-sponsored party called the Union of the Russian People demonstrated against the manifesto, proclaimed their undying loyalty to the autocrat, and organized their own storm troops, or Black Hundreds, which killed more than three thousand Jews in the first week after the issuance of the manifesto.

The armies that had returned from the Far East remained loyal to the government. On the left, the Bolsheviks and SRs made several attempts to launch their violent revolution but failed, and the government was able to arrest their leaders and to put them down after several days of street fighting in Moscow in December 1905.

In the center, one group of propertied liberals, pleased with the manifesto, urged that it be used as a rallying point for a moderate program; they were the Octobrists, so called after the month in which the manifesto had been issued. The other moderate group, the Kadets, wished to continue to agitate by legal means for further immediate reforms. But the fires of revolution burned out by early 1906 as Witte used the army to put down any new disturbances.