By the early eighteenth century, Poland and the Ottoman Empire still bulked large on the map, but both states suffered from incompetent government, a backward economy, and the presence of large national and religious minorities. The Orthodox Christians in Catholic Poland and Muslim Turkey were beginning to look to Russia for protection.

Moreover, the evident decay of both states stimulated the aggressive appetites of their stronger neighbors. Poland would disappear as an independent power before the end of the century, partitioned by Russia, Austria, and Prussia. Turkey would hold on, but was already beginning to acquire its reputation as “the Sick Man of Europe.”

The Polish government was a political curiosity. The monarchy was elective: Each time the throne fell vacant, the Diet chose a successor, usually the candidate who had offered the largest bribes, and sometimes even a foreigner. Once elected, the king was nearly powerless. The Diet was dominated by the nobility and since the 1650s had practiced the liberum veto, whereby any one of its members could block any proposal by shouting “I do not wish it!” The Diet was not a parliament but as assembly of aristocrats, each of whom acted as a power unto himself; unanimity was therefore almost impossible. This loosely knit state had no regular army, no diplomatic corps, no central bureaucracy.

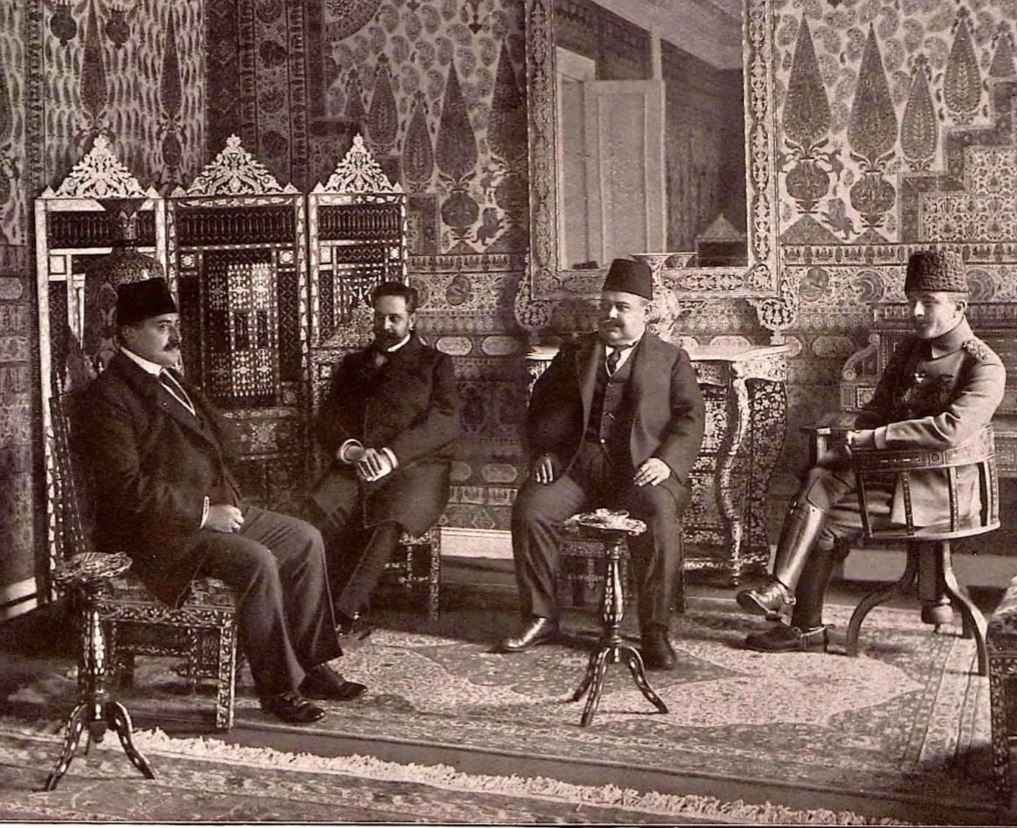

The Ottoman Empire was still a functioning state, yet it was falling further and further behind the major European powers, particularly in fiscal stability and technology. Not until the nineteenth century did it produce a sultan who would attempt the kind of massive assault on tradition that Peter the Great had mounted.

In the eighteenth century, with rare exceptions, the sultans were captives of harem intrigue and could do little to discipline such powerful groups as the janissaries—members of the elite military caste—who exploited their privileges and neglected their soldierly duties. This backward government did at least govern, however, and it showed considerable staying power in war. The so-called Polish and Turkish questions would dominate international politics for the next half-century.