What to Christians was persecution, to the Roman authorities was simply the performance of their duty as defenders of public order against those who seemed to be traitors to the Empire or irresponsible madmen. The Christians ran afoul of Roman civil law not so much for their beliefs and practices as for their refusal to make concessions to paganism. To cultivated Greeks and Romans, Christians seemed wild enthusiasts; to the masses they were disturbers, cranks, revolutionaries.

The Empire was not very deeply concerned with details about the morals and faiths of its hundreds of component city-states, tribes, and nations. Scores of gods and goddesses, innumerable spirits and demons, filled the minds of the millions under Roman rule, and the rulers were willing to tolerate them all as part of the nature of things.

There was, however, a practical limit to this religious freedom. To hold this motley collection of peoples in a common allegiance and give them something like the equivalent of a modern national identity, the emperor was deified. Simple rites of sacrifice to him were added to local religious customs. Those who did not believe in the customary local gods—and such disbelief was widespread in the Roman Empire—had no trouble in doing what was expected of them, for they did not take any religion, new or old, with undue seriousness.

The Christians, however, would not sacrifice to the emperor any more than the Jews of old would sacrifice to Baal. Indeed, they felt that if an emperor pretended to be a god, he revealed that he was in fact a devil. The more cautious administrators of the growing Christian church were anxious to live down their reputation for dis¬orderliness, and they did not want to antagonize the civil authorities. But sacrifice clearly was a “thing of God’s”; the dedicated Christian, then, could not make what to an outsider or a skeptic was merely a decent gesture of respect to the beliefs of others. Moreover, if he was a very ardent Christian, he might feel a sacrifice to Caesar was wicked, even when performed by non-Christians.

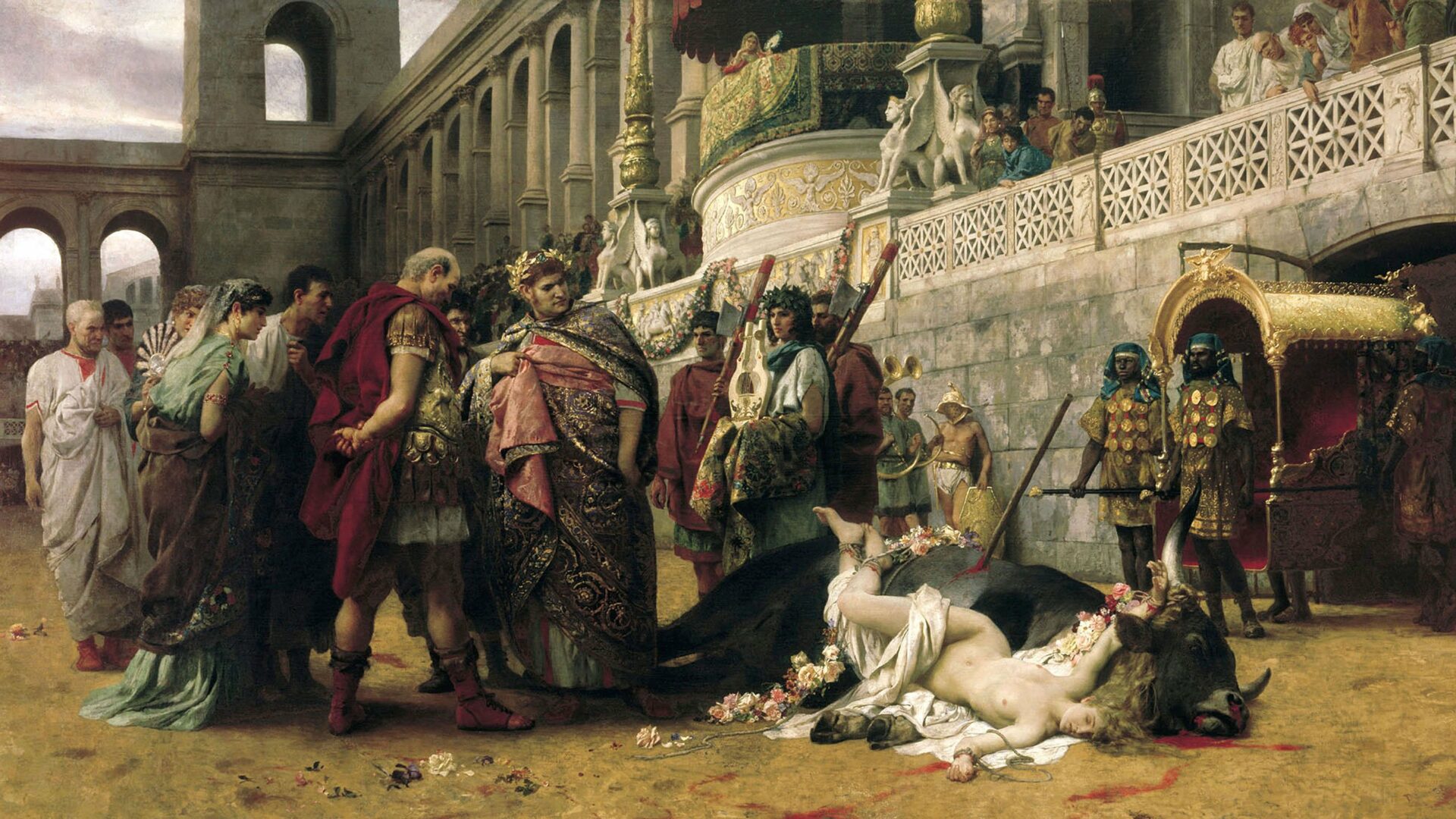

The imperial authorities did not consistently seek to stamp out the Christian religion, and persecutions were sporadic over the course of three centuries, varying in severity at different times and different places. The first systematic persecution was under Nero in 64, who had some of the Christians torn to pieces by wild beasts and others set alight as torches in the dark. A generation or so later, in c. 110-111, an imperial administrator, Pliny the Younger, wrote from his post in Asia Minor to the emperor Trajan that he was puzzled about how to treat the Christians, and asked for instructions.

Should he make allowance for age, or punish children as severely as adults? Should he pardon a former Christian who now recanted? Should he punish people simply as Christians, or must he have evidence that they had committed the crimes associated publicly with their name? Up to now Pliny had asked the accused if they were Christians, and if they three times said they were, he had them executed. Pliny had interrogated the alleged Christians partly on the basis of an anonymous document listing their names. He had acquitted all who denied that they were Christians, who offered incense before the emperor’s statue, and who cursed Christ, and all who admitted that they had once been Christians but had recanted.

Trajan answered with moderation that Pliny had done right. He left the question of sparing children to Pliny’s own judgment. He said that Christians need not be sought out, though any who were denounced and found guilty must be punished, as Pliny had done. Any who denied that they were Christians, even if they had been suspect in the past, should gain pardon by penitent prayer to the Roman gods. As for “any anonymous documents you may receive,” they “must be ignored in any prosecution. This sort of thing creates the worst sort of precedent, and is out of keeping with the spirit of our times.” Trajan thus established the guidelines by which the Romans dealt with the Christians under the law until the reign of Decius, in 249-251, when vigorous persecution was renewed.

Alone among the emperor’s subjects, however, unrepentent Christians might be killed “for the name alone,” presumably because their “atheism,” as Trajan saw it, threatened to bring down the wrath of the gods on the community that tolerated it. The Jews, equally “atheist” in this sense, could be forgiven because they were continuing to practice their ancestral religion—worthy in itself in Roman eyes—and because Rome had long since officially tolerated the Jewish faith, provided that the Jews did not rebel against the Roman state. A single act of religious conformity brought acquittal.

Not until the third century, when the Roman world felt threatened from within and without, did persecutions become frequent and severe. By then Christians were far more numerous, as the faith had spread rapidly. After an anti-Christian riot in Alexandria, Decius commanded that on a given day everyone in the Empire must sacrifice to the gods and obtain a certificate to prove having done so. The pope, the bishops of Antioch and Jerusalem, nineteen Christians of Alexandria, and six at Rome are known to have been executed.

No bishop in North Africa died, though there were cases of torture. In Spain two bishops recanted. Many Christians who had not obeyed the edict escaped arrest afterward for failing to have the certificate; some hid until the persecution had died down, and in parts of the Empire the edict was not enforced. In the Latin West others bribed officials to issue them false certificates saying that they had sacrificed; later they were received back into their churches with some protest. In the Greek East, the same bribery probably took place but apparently was not regarded as sinful.

Under Valerian in 257-259, the government for the first time tried to interfere with the assembly of Christians for worship, and the clergy were ordered to sacrifice. After Valerian had been captured by the Persians, however, his successor granted toleration. But the systematic persecution begun in 303 by Diocletian was the most intense of all, especially in the East, where it lasted a full decade, as compared to about two years in the West. Churches were to be destroyed and all sacred books and church property handed over. In Palestine nearly a hundred Christians were martyred.

Persecution as a policy was a failure; it did not eliminate Christianity. Quite the contrary—many influential persons in the Empire had become Christians. Moreover, persecution did not avert disasters, which continued to befall the Roman state whether it persecuted Christians or not. In 311 and 313, respectively, the persecuting emperors Galerius and Maximinus officially abandoned the policy. In 313 the Edict of Milan confirmed that Christians might exist again, own property, and build their own churches, so long as they did nothing against public order. The state was to be neutral in matters of religion.