Victory seemed to give the Democrats a clear mandate to marshal the resources of the federal government against the depression. Franklin Roosevelt took office on March 4, 1933, during a financial crisis that had closed banks all over the country. He at once summoned Congress to an emergency session and declared a bank holiday.

Gradually the sound banks reopened, and the first phase of the New Deal began. In the early months of 1933 the mere fact that a national administration was trying to do something about the situation was a powerful boost to national morale. The nation emerged from the bank holiday with a new confidence, repeating the phrase from Roosevelt’s inaugural address that there was nothing to fear but “fear itself.”

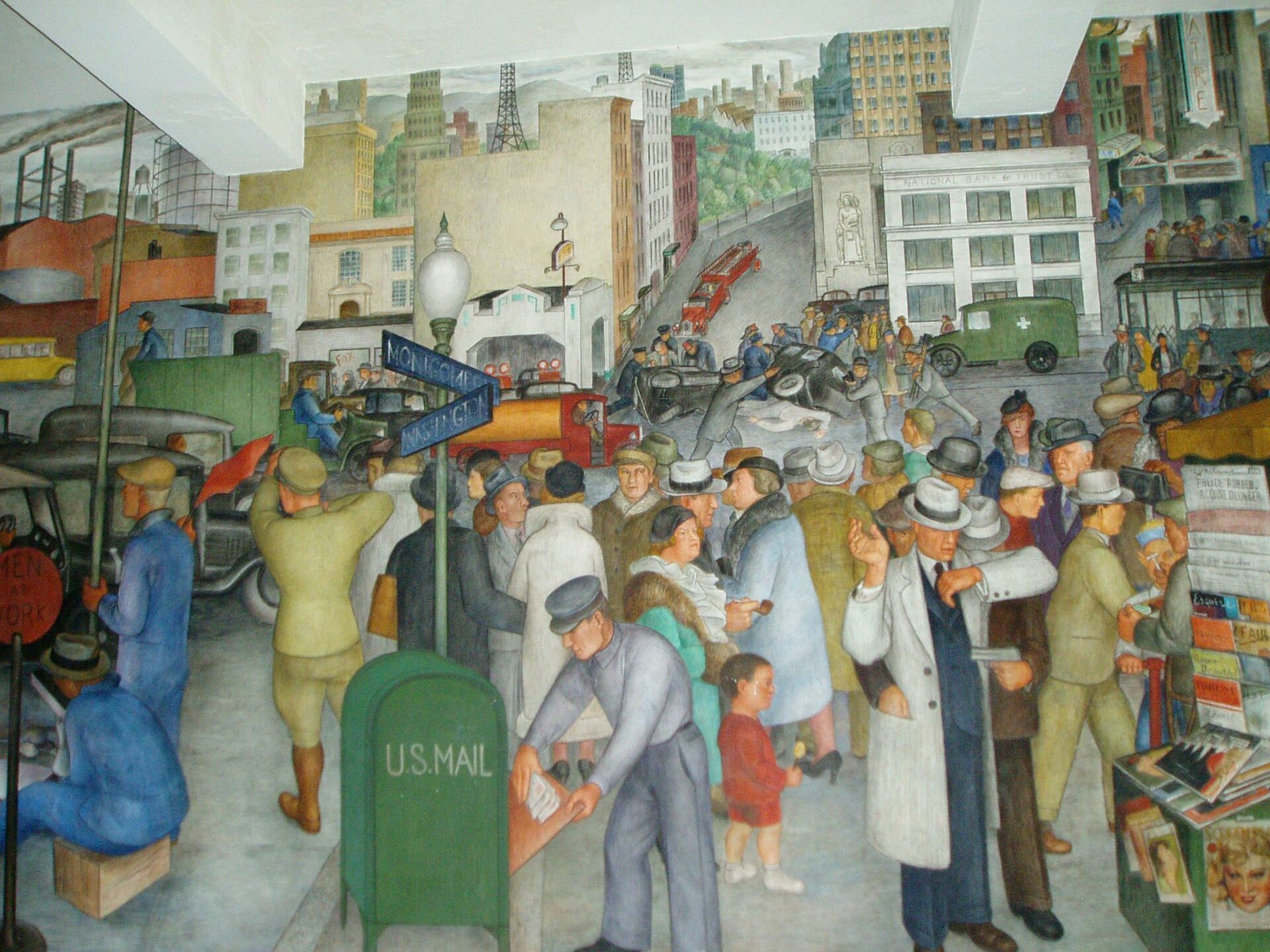

The New Deal was a series of measures aimed in part at immediate difficulties and in part at permanent changes in the structure of American society. It was the application to the United States, under the special pressures of the Great Depression, of measures that were being tried in European countries, measures often leading to the welfare state.

By releasing the dollar from its tie with gold, the short-term measures of the New Deal aimed to lower the price of American goods in a world that was abandoning the gold standard. They aimed to thaw out credit by extending the activities of the RFC and by creating such new governmental lending agencies as the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation.

They aimed to relieve unemployment by public works on a large scale, to safeguard bank deposits by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and to regulate speculation and other stock-market activities by the Securities and Exchange Commission. The National Recovery Act (NRA) of 1933 set up production codes in industry to regulate competition and to ensure labor’s right to organize and carry on collective bargaining. The historical significance of many of these innovations rested in the fact that they were undertaken not by private business or by state or local authorities but by the federal government.

The long-term measures of the New Deal were, of course, more important. The Social Security Act of 1935 introduced to the United States on a national scale the unemployment insurance, old-age pensions, and other benefits of the kind that Lloyd George had brought to Britain. By extending and revising tax structures, including the income tax authorized by the Sixteenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1913, Congress in effect redistributed wealth to some degree.

Congress also passed a series of acts on labor relations that strengthened and extended the role of organized labor. A series of acts on agriculture regulated crops and prices and provided subsidies on a large scale. And a great regional planning board, the Tennessee Valley Authority, used government power to make over the economic life of a relatively backward area by checking the erosion of farmlands, instituting flood control, and providing cheap electric power generated at government-built dams.

The presidential election of 1936 gave Roosevelt an emphatic popular endorsement. Yet the New Deal never regained the momentum it had in his first term. In retrospect it seems evident that the measures taken by the Roosevelt administration, combined with the resilience of American institutions and culture, pulled the United States at least part way out of the depression. Full recovery, however, did not come until the boom set oil by the outbreak of World War II.

The spring and summer of 1939 found Americans anxious to remain neutral if Europe should persist in going to war. Roosevelt and his Republican opponents had been for some time exchanging insults. Yet in the pinch of the international crisis of 1939 it became clear that, although the nation was not completely united, it was not deeply divided. As so often in American history, the violence of verbal politics—in which language is often used with more vehemence than in Europe—masked a basic unity.

When, on September 1, the war came, the United States had already made manv efforts to enlist the support of the Latin American states, so that the New World might once again redress the grievances of the Old. In 1930, before the so-called Roosevelt Revolution in American diplomacy, President Hoover’s State Department issued a memorandum specifically stating that the Monroe Doctrine did not concern itself with inter-American relations, but was directed against outside intervention in the affairs of the Western Hemisphere.

The United States was no longer to land Marines in a Central American republic; rather, American policy was to try to strengthen hemispheric solidarity. On these foundations, President Roosevelt built his celebrated Good Neighbor policy toward the other American nations, withdrawing the United States from Cuba and beginning the liquidation of formal American empire.