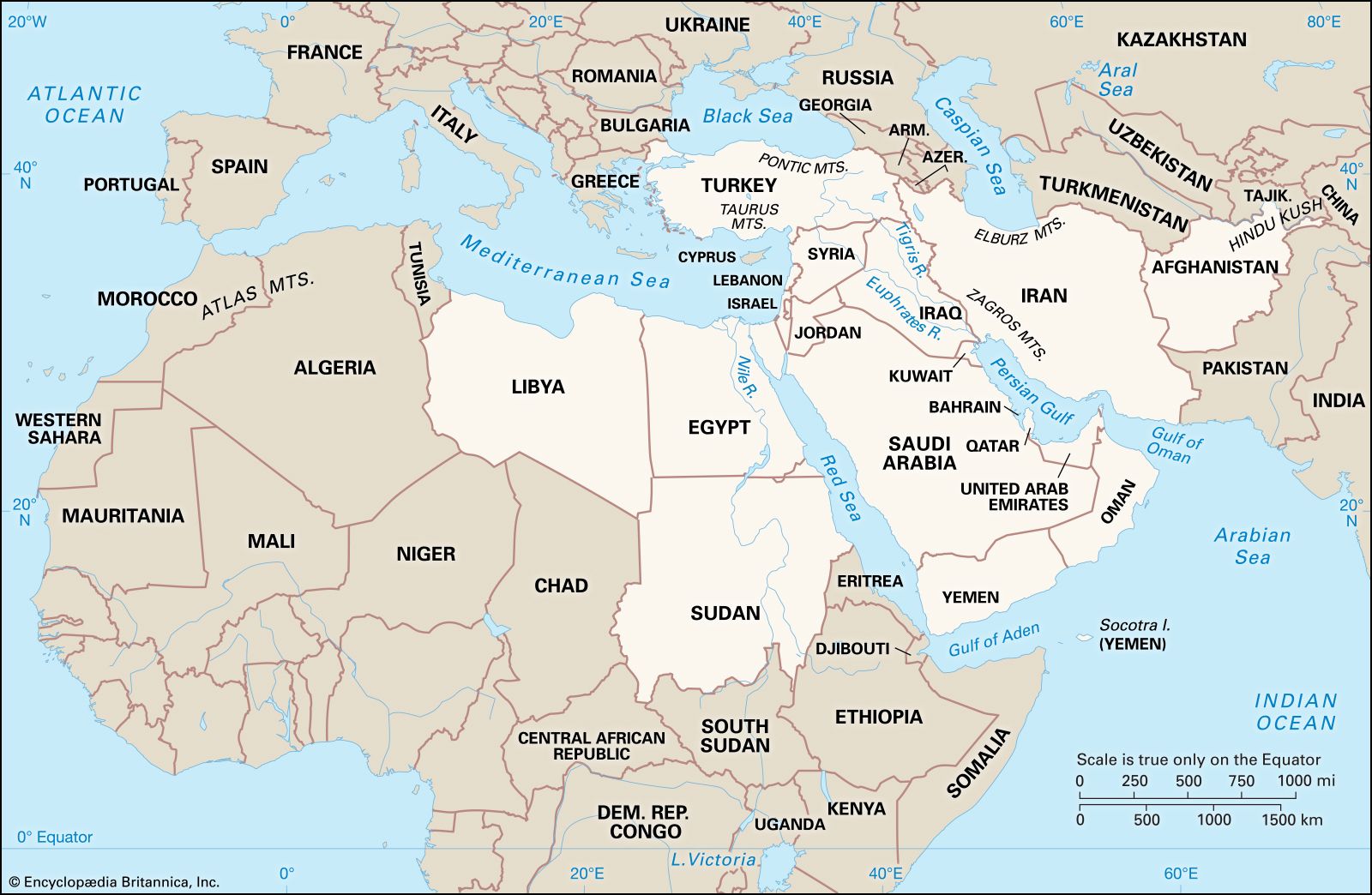

In Saudi Arabia, in the small states along the Persian Gulf, and in Iraq and Iran, the Middle East possessed the greatest oil reserves in the world. Developed by European and American companies that paid royalties to the local governments, these oil resources influenced the policies of all the powers.

Many of the oil-producing states had banded together in 1960 to form the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), and they quickly discovered a powerful new weapon in international diplomacy. They used the mechanism of oil pricing and threatened increases both to frighten Western industrial nations dependent on a continued flow of oil and to manipulate Western foreign policies toward Israel.

When the British withdrew their forces from Palestine in 1948, the Jews proclaimed the state of Israel and secured its recognition by the United Nations. The Arab nations declared the proclamation illegal and invaded the new state from all directions. Outnumbered but faced by an inefficient enemy, the Israelis won the war.

A truce that was not a formal peace was patched together under the auspices of the United Nations in 1949. Israel secured more of Palestine than the UN had proposed, taking over the western part of Jerusalem, a city the UN had proposed to neutralize. However, the eastern part, or “old city” of Jerusalem together with eastern Palestine, remained in the hands of the Arab state of Jordan.

During the 1948 war almost a million Palestinian Arabs fled from Israel to the surrounding Arab states. The United Nations organized a special agency that built camps and gave relief to the refugees and tried to arrange for their permanent resettlement. The Arab states, however, did not wish to absorb them, and many refugees regarded resettlement as an abandonment of their belief that the Israelis would soon “be pushed into the sea,” and that they themselves would then return to their old homes. This problem made the truce of 1949 very delicate.

The new state of Israel continued to admit as many Jewish immigrants as possible, from Europe, North Africa, Yemen, and later the Soviet Union. The welding of these human elements into a single nationality was a formidable task. Much of Israel was mountainous, and some of it was desert. The Israelis applied talents and training derived from the West to make the best use of their limited resources, and they depended on outside aid, especially from their many supporters in the United States.

In 1952, less than four years after the Arab defeat in Palestine, revolution broke out in Egypt, where the corrupt monarchy was overthrown by a group of army officers led by Gamal Abdel Nasser (1918-1970). They established a republic, encouraged the emancipation of women, and pared down the role of the conservative religious courts.

Only one parry was tolerated, and elections were closely supervised. As an enemy of the West, which he associated not only with colonialism but with support for Israel, Nasser turned for aid to the Soviets. Czechoslovak and Soviet arms flowed into Egypt, and Soviet technicians followed.

Nasser’s chief showpiece of revolutionary planning was to be a new high dam on the Nile at Aswan. He had expected the United States to contribute largely to its construction, but in mid-1956 the United States changed its mind. In retaliation, Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal, previously operated by a Franco-British company, and announced that he would use the revenues thus obtained to build the dam. For several months, contrary to expectations, the new Egyptian management kept canal traffic moving smoothly. The French and British governments, however, secretly allied themselves with Israel.

In the fall of 1956 Israeli forces invaded Egyptian territom and French and British troops landed at Suez. The Soviet Union threatened to send “volunteers” to defend Egypt. Nor did the United States, angry at its British and French allies for concealing their plans, give its support to them.

With the United States and the Soviet Union on the same side of an issue for once, the United Nations condemned the British-French-Israeli attack, and eventually a United Nations force was moved into the Egyptian-Israeli frontier areas, while the canal, blocked by the Egyptians, was reopened and finally bought by Nasser.

After the Suez crisis, Nasser’s economic policy was governed by the grim struggle to support a fast-growing population. He undertook programs to reclaim land from the desert by exploiting underground water, and to limit the size of landholdings so that landless peasantry might hope to acquire land. To provide more jobs and to bolster national pride, he also accelerated the pace of industrialization. Most foreign enterprises in Egypt were nationalized.

In 1967 Nasser demanded that the United Nations troops that had kept the Egyptians and Israelis separated since 1956 be removed. UN Secretary General U Thant complied. The Egyptians began a propaganda barrage against Israel and closed the Strait of Tiran, the only water access to the newly developed Israeli port of Elath. The Israelis then struck the first blow in a new war, destroying the Egyptian air force on the ground and also hitting at the air forces of the other Arab states.

In six days they overran the Sinai peninsula, all of Palestine west of the Jordan, including the Jordanian portion of Jerusalem, and the Golan heights on their northern frontier with Syria, from which the Syrians had been launching raids for several years. This third Arab-Israeli war in nineteen years ended in an all-out Israeli victory.

It was a humiliation not only for Nasser but also for the Soviet Union, which had supplied much of the equipment that had been abandoned as the Egyptian army retreated. The Soviets moved vigorously to support the Arab position, arguing their case in the United Nations, denouncing Israel, and rearming Egypt. Israeli armies remained in control of all the territory they had occupied.

Had negotiations begun soon after the war, much of this territory could perhaps have been recovered, but as time passed the Israeli attitude hardened, and it became difficult for any Israeli government to give up any part of Jerusalem or the Golan heights, whose possession ensured Israeli territory against Syrian attack. Sinai, the Gaza strip, and perhaps the West Bank of the Jordan might be negotiable.

But the Arabs, led by Nasser, refused to negotiate directly with the Israelis or to take any step that would recognize the existence of the state of Israel. Rearmed and retrained partly by the Soviets, the Egyptians repeatedly proclaimed their intention of renewing the war. Israel existed as an armed camp, its men and women serving equally in the military forces, ever prepared for an attack.

In 1969 and 1970 tension again mounted dangerously in the Middle East. Arab Palestinians organized guerrilla attacks on Israel or on Israeli-occupied territory from Jordan, Syria, and Lebanon. The Lebanese government—precariously balanced between Christians and Muslims—was threatened by the Palestinian guerrillas and forced to concede Lebanese territory nearest the Israeli frontier.

In various airports—Zurich, Athens, Tel Aviv— terrorists attacked planes carrying Israelis. At times the Palestinian Arab terrorist movement took on the aspects of an independent power, negotiating with the Chinese, compelling Nasser to modify his pronouncements, and demanding that its leaders be heard in the United Nations. In the autumn of 1970 terrorists hijacked four large planes—Swiss, British, German, and American—in a single day, holding the passengers as hostages in Jordan for the release of certain captives of their own.

During the tense negotiations that followed, full-scale hostilities broke out between the Arab guerrillas and the Jordanian government. The Syrians intervened on the side of the guerrillas, and the threat of American intervention on the side of Jordan’s King Hussein (1935– ) and of a Soviet response was suddenly very real. Jordanian successes, Syrian withdrawal, and American and Soviet restraint helped the critical moment pass.

Just as grave was the continual Arab-Israeli confrontation in Egypt. Here Egyptian raids across the Suez Canal into Israeli-occupied territory in the Sinai were followed by Israeli commando raids into Egyptian territory on the west side of the canal and by Israeli air raids deep into Egypt. During 1970 the installation of Soviet missile sites near the canal forced the suspension of the Israeli attacks.

But the Soviet involvement in Egyptian defense also threatened open confrontation between the Soviet Union and the United States. To avoid this danger, the United States, Britain, and France held four-power discussions with the Soviets on the Arab-Israeli conflict. With the Soviets totally committed to the Arab side and the French increasingly pro-Arab, with Britain balancing between the two sides, and with the United States trying to help Israel but determined to avoid another entanglement like Vietnam, the Israelis regarded with skepticism the possibility of any favorable solution emerging from the big powers’ discussions.

They insisted that only direct talks between themselves and the Arabs could lead to a satisfactory settlement. Arab insistence that a return of all occupied territory must precede any discussions rendered such meetings impossible. In the summer of 1970, however, the Egyptians and Israelis agreed to a cease-fire. But as hopes were renewed that discussions might at least begin, President Nasser died suddenly, to be replaced by Mohammed Anwar el-Sadat (1918-1981), who pledged himself to regain all occupied territories.

Sadat became suspicious of the Soviets’ intentions, and in 1972 he expelled them from Egypt. Determined to regain Egypt’s lost lands, he attacked Israeli-held territory, in concert with Syrian forces, on the Jewish holy day of Yom Kippur in October 1973. For the first time the Israelis were caught by surprise, and the Egyptians inflicted heavy losses.

An Israeli counterattack turned the Egyptians back, however, and in November a truce was signed in the Sinai by Israel’s prime minister, Golda Meir (1898-1978). Oil diplomacy now demonstrated its force. At the outbreak of the war, the Arab oil-producing states cut off the flow of oil to Europe and the United States to force the West to bring pressure on Israel. While Americans had alternative sources of supply, many European nations had none, and the Arabs’ policy had the desired response of pressure on Israel.

Sadat, however, was convinced that his people needed relief from constant conflict. In 1977 he committed himself to achieving Egyptian-Israeli peace. Flying to Israel, he addressed the parliament and met with the new Israeli prime minister, Menachim Begin (1913— ). Begin had taken a particularly hard line on all issues relating to the Arab states, including the question of a homeland for the Palestinians. Though immediately condemned by most Arab states, Sadat persevered, and both he and Begin later accepted an invitation to meet with the American president, Jimmy Carter, at Camp David outside Washington. There a series of accords was worked out in September 1978 as the basis for future negotiations on a wide range of Middle Eastern questions.

But the “spirit of Camp Daviddid not last. The Arab states refused to join Egypt in negotiations. The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), as the principal voice for the Palestinian refugees, mounted an increased terrorist campaign. PLO leader Yasir Arafat (1929— ), helped by growing Western disenchantment with Begin’s tough bargaining positions, began to make inroads into Western support for Israel.

Then three blows disrupted the delicate peace once again. In October 1981 Sadat was assassinated in Cairo by Muslim extremists. Two months later the Israeli parliament annexed the Golan heights. Charges of bad faith drove a wedge between the new Reagan administration and Israel. Then in 1982 the long explosive situation in Lebanon was ignited.

Determined to drive the Palestinians out of south Lebanon, the Israeli army had previously staged a massive invasion in 1978 and had withdrawn in favor of a United Nations peacekeeping force. However, Israel continued to aid Christian forces in Lebanon. A second Israeli occupation of southern Lebanon occurred in 1980 in retaliation for a raid on a kibbutz (Israeli collectivist agricultural settlement). Israel next declared Jerusalem to be its capital. In response to an Israeli attack on Syrian helicopters, Syria moved Soviet-built surface-to-air-missiles into Lebanon. In June 1981 an Israeli air strike on an Iraqi atomic reactor near Baghdad was widely condemned even by Israel’s friends.

Even though the new Egyptian leader, Hosni Mubarak (1929– ), stood by the spirit of Camp David, the Arab-Israeli conflict continued to make the Middle East the world’s most unstable region. Begin, narrowly reelected in 1981, was determined not to appease the Palestinians. In the fall of 1982 he and his military advisers decided that they must at last clear the Palestinians out of all of Lebanon; They mounted a massively destructive attack on the city of Beirut. Shortly thereafter a Lebanese Christian Phalangist militia was allowed—probably with Israeli knowledge and clearly without sufficient Israeli supervision—to move into two large Palestinian refugee camps and massacre men, women, and children.

Even as Israel moved to institute a full inquiry into the killings at the Lebanese camp, tensions ran high in Israel and throughout the world. The investigating commission found several top Israeli military and government officials “indirectly responsible,” which led to their demotion or dismissal. Weary and in poor health, Begin resigned in October 1983, and Israeli politics fell into a period of instability.

Iraq, at first closely aligned with the British after World War II, had ousted its monarchy and proclaimed a leftist, pan-Arab republic in 1958. Extremists of the left and right thereafter subjected the country to a series of coups and abortive coups. In 1968 the Bdath (Renaissance) party took control, and within three years one of its activists, Saddam Hussein (1937– ), had emerged as leader.

The party ruled by decree; in 1972 it signed an aid pact with the Soviet Union and began to receive heavy armaments in great quantities, and it supported Syria against Israel. Between 1969 and 1978 Iraq developed the most terror-ridden regime of the Arab states. Iraq and Syria—also in the hands of a Ba’ath party—soon became enemies.

Saddam Hussein had sought to conciliate Iraq’s largest minority, the Kurds, who had been in sporadic rebellion for decades in quest of the autonomy promised to them by the Treaty of Sevres in 1920, a promise broken by the Treaty of Lausanne three years later. The Kurdish leader, Mustafa al-Barzani (1901-1979), led a revolt in Iraq from 1960 to 1970 and, convinced that he could not trust Saddam, renewed the rebellion in 1974, continuing until his death. Iran had supported the Kurds until 1975, and the continued revolt led to Iraqi bombing of Kurdish villages in neighboring Iran.

In September 1980 Iraq and Iran entered into open warfare with air strikes and heavy ground fighting. The war expanded into the Persian Gulf in 1984, with attacks on oil fields and oil tankers. This fierce war ended in August 1988, when Iraq accepted a United Nations resolution for a cease-fire. Saddam then turned his forces against the Kurds once again, thoroughly crushing all opposition. He also continued to acquire the instruments of war from a variety of sources until, by 1990, he had one of the largest and best equipped armies in the world. The Western nations, particularly the United States, had thus far been content to see Iraq engage Iran, which had turned against the West and decreed the United States to be “the Great Satan.”

Saddam Hussein declared in July 1990 that some Persian Gulf states, inspired by America, had conspired to keep oil prices down through overproduction and that Iraq’s oil-rich and small neighbor Kuwait was part of an “imperialist-Zionist plan” to deny just free market prices to Iraq for its oil. At the end of the month the OPEC ministers agreed to a rise in oil prices, though not sufficiently high to satisfy Saddam.

Iraq had claimed sovereignty over Kuwait since 1961, insisting that it was the artificial creation of the Saudi monarchy supported by the West, and before dawn on August 2 Saddam sent Iraqi tanks and infantry into Kuwait, occupying and looting the state. Later that day the United States denounced Iraq’s aggression, the United Nations condemned the invasion and demanded the withdrawal of Iraqi troops from Kuwait, and the Soviet Union suspended arms sales to Saddam’s army. Fourteen of the Arab League’s twenty-one members also voted against Iraq’s aggression, and the United Nations called for a boycott of Iraq.

The West, as well as Saudi Arabia, hoped that economic and moral pressure would force Iraq to withdraw. The United States President, George Bush, wanted a firm deadline to be given to Saddam, and the UN named January 15, 1991. Fearful that Iraq might launch an attack on Saudi Arabia, the Western nations began a massive troop movement to take up positions along the Iraqi and Kuwaiti borders. With financial aid from Saudi Arabia, West Germany, and Japan, and troop contingents from several Western nations, the United States took the lead in putting pressure on Saddam to withdraw.

When Saddam had not done so by the announced deadline, the United States led a concerted air attack against Iraq on January 16. Iraq replied by sending missiles against Saudi and Israeli targets, by the latter hoping to draw a response from Israel that would fracture the anti-Iraq coalition and lead to the withdrawal of some of its Arab members. Jordan, caught between the contending forces, turned from its formerly pro-Western stance to show increasing sympathy for Iraq.

In just two months, the coalition had thoroughly defeated the Iraqi armies, and Saddam Hussein had agreed to accept UN observers, to destroy Iraq’s nuclear stores, and to rescind his annexation of Kuwait. In the United States, President George Bush’s (1924— ) popularity soared, and the sense of disenchantment with the military, pervasive since the war in Vietnam, was replaced with widespread patriotism and enthusiasm for the victorious American generals, in particular the Chief of Staff, Colin Powell (1937— ) and the commanding officer in Kuwait and Iraq,

General Norman Schwartzkopf (1934— ). There were unforeseen results of the war as well: As the Iraqis retreated from Kuwait, they set fire to virtually all of that nation’s oil wells, sending into the Persian Gulf unprecedented airborne pollution that would take years to correct; and millions of Kurds fled from Iraq into Iran and Turkey. The United Nations coalition failed to achieve one of its goals in the Gulf War: bringing down Saddam Hussein, who remained firmly in power.

He employed chemical weapons in his ongoing war against the Kurds, attempted to defy the teams sent by the UN to verify that Iraq had dismantled its nuclear capacity, and in 1994 declared himself to be prime minister as well as president. The Middle East remained a powder keg, though there was hopeful movement on the Arab-Israeli conflict.

When the Labor party of Yitzhak Rabin (1922— ) was elected in 1992, Rabin called for reconciliation with Israel’s neighbors, and despite repeated incidents of terrorism, Rabin and Arafat met to conclude an agreement in September 1993 by which the PLO recognized Israel’s right to exist and Israel recognized the PLO as the representative of the Palestinians.

Self-rule was extended to the Gaza strip and in the West Bank, and on July 25, 1994, Israel and Jordan signed a declaration ending their state of war forty-six years after it had begun.