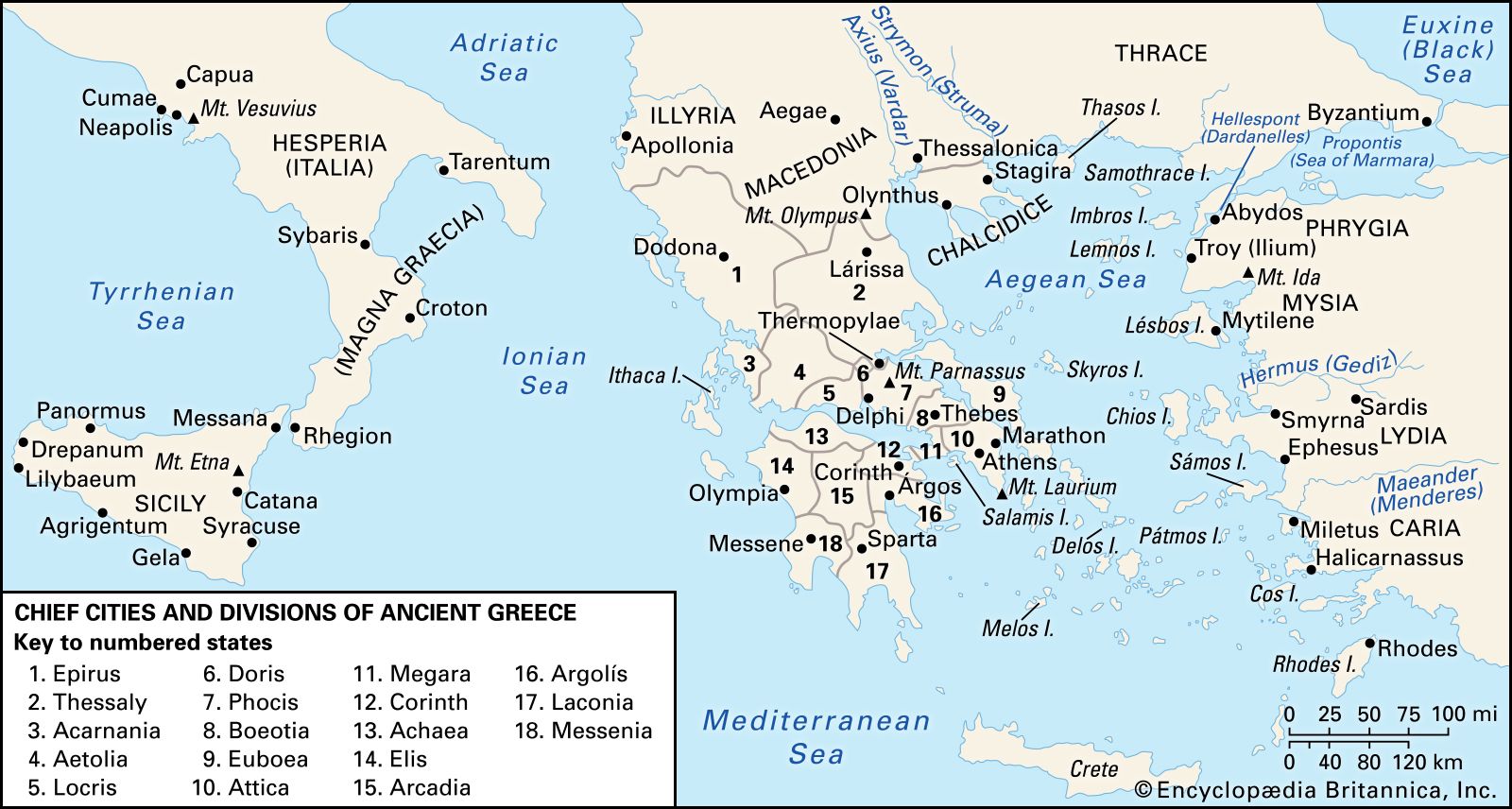

The new Persian rulers would not allow their subjects political freedom, which was what the now-captive Ionian Greek cities most valued. Their prosperity declined, as the Persians drew away from Ionia the wealth from the trade routes that had formerly so enriched Aegean towns. By 513 B.C. the Persians had crossed the Bosporus, sailed up the Danube, and moved north across modern Romania into the Ukraine in a campaign against a nomadic people called Scythians. Though tentative, the new advance into Europe alarmed the Greeks; it looked as if Darius would move south against European Greece from his new base in the northern Balkans.

Some of the Greek poleis were hostile to the Persians, but there were others that had pro-Persian rulers. Pisistratus’s son Hippias had taken refuge at the Persian court, awaiting his return to Athens, but the Athenians refused to accept him and helped the captive Ionian cities to resist Persian rule. The Ionians rebelled in 499; with Athenian assistance, they burned down Sardis, the former Lydian capital that was now the Persian headquarters in Asia Minor. Many other Greek cities then joined the rebellion.

The Persians struck back with fury and by 495 B.C. had defeated the Ionian fleet. They burned the most important Ionian city, Miletus, massacred many of its men, and deported its women and children into slavery. By 493 B.C. the Ionian revolt was over, and in the next two years the Persians extended their authority along the northern coasts of Greece proper, directly threatening Athens. It was probably Hippias who advised the Persian commanders to land at Marathon in a region once loyal to his father, Pisistratus, about twenty-five miles north of Athens. There a far smaller Athenian force, decisively led by Miltiades, a professional soldier who had served the Persians and angered Darius, defeated his former colleagues in 490 and for ten years ended the Persian threat to Greece.