Early in Nicholas’s reign, Russian professors and students, influenced by German philosophers, were devoting themselves to discussions on art, philosophy, and religion. Russian universities were generally excellent and at the cutting edge of the great variety of modernizing ideas associated with the nineteenth century.

Many intellectuals outside the universities followed suit. These were the first groups to be known as intelligentsia, originally a class limited to Russia, though the concept of the intelligentsia soon spread to the rest of the European Continent and drew upon themes from the Enlightenment.

By the 1830s the intelligentsia was beginning to discuss Russia’s place in the world, and especially its relationship to the West. Out of its debates arose two important opposing schools of thought: the Westerners and the Slavophiles.

The Westerners stated their case in a document called the Philosophical Letter, published in 1836 though written earlier. Its author, Peter Chaadaev (c. 17941856), lamented the damaging effect of Byzantine Christianity and Tatar invasion upon Russian development and declared that Russia had made no contribution of importance to the world.

Nicholas I had Chaadaev certified as insane and commanded that he be put under house arrest, while the journal in which the letter appeared was banned and its editor sent into exile. Yet despite scorn and censorship, the Westerners continued to declare that Russia was a society fundamentally like the West, though far behind it, and that Russia should now catch up.

In contrast, the Slavophiles vigorously argued that Russia had its own national spirit. Russia was, they maintained, essentially different from the West. The orthodox religion of the Slays was not legalistic, rationalistic, and particularistic, like that of the Roman Catholic states of the West, but emotional and organically unified.

The Slavophiles attacked Peter the Great for embarking Russia on a false course. The West ought not be imitated, but opposed. The Russian upper classes should turn away from their Europeanized manners and look instead for inspiration to the Russian peasant, who lived in the truly Russian institution of the village commune. Western Europe was urban and bourgeois; Russia was rural and agrarian. Western Europe was materialistic; Russia was deeply spiritual.

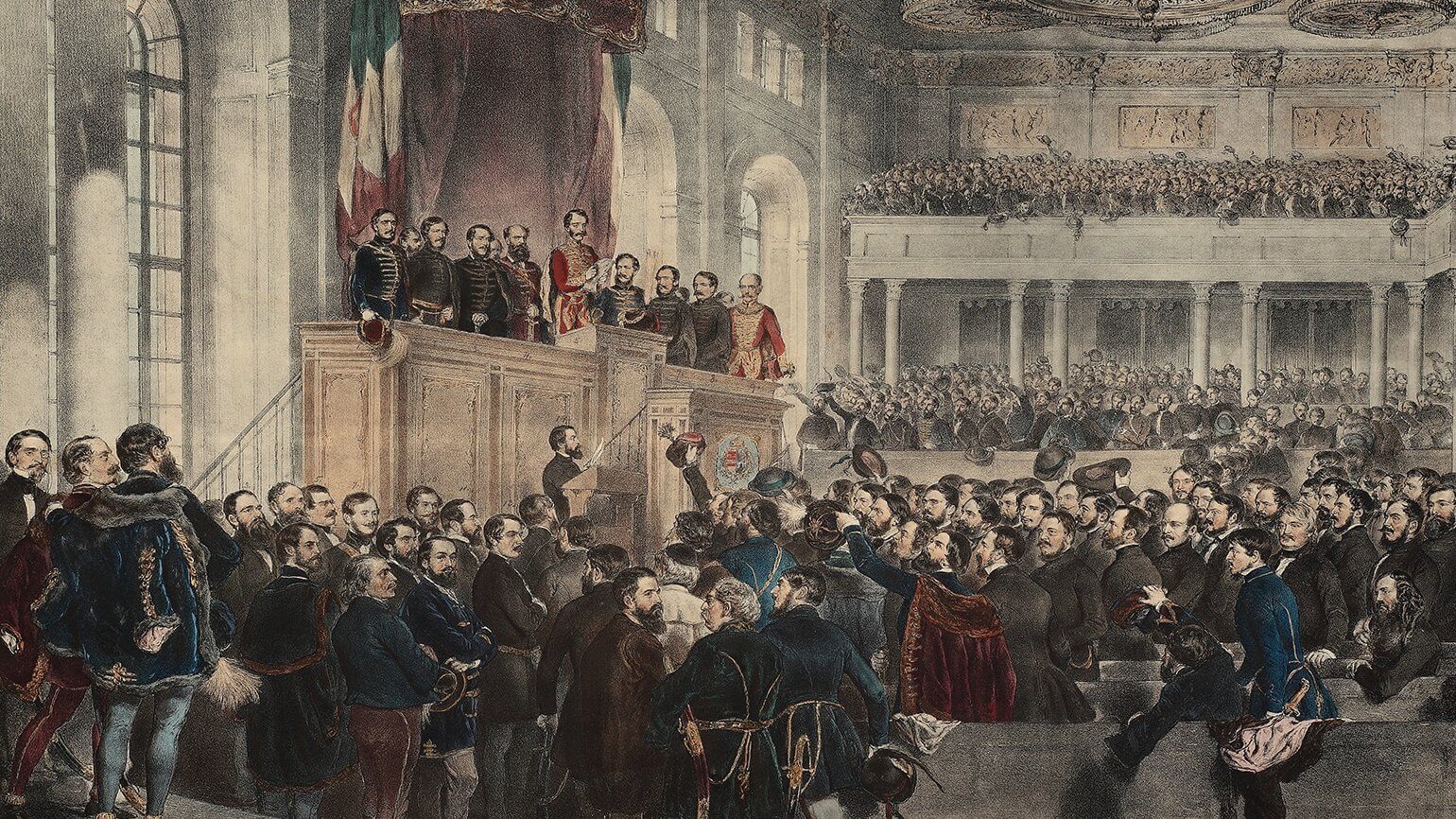

This view also led to a demand for a thorough change in the country, however. The Slavophiles opposed the tyranny and the bureaucracy of Nicholas I as bitterly as did the Westerners, but they wanted a patriarchal, benevolent monarchy of the kind they argued had existed before Peter the Great, instead of a constitutional regime on the Western pattern. Instead of a central parliament, they looked back to the feudal Muscovite assembly, to the zemski sobor, and to other institutions of czardom before Peter.

Michael Bakunin (1814-1876) pushed these ideas to an extreme. He was a tactician of violence who advocated “anarchism, collectivism, and atheism.” He looked forward to a great revolution spreading perhaps from Prague to Moscow and thence to the rest of Europe, followed by a tight dictatorship; beyond this he was entirely vague about the future. Atheism was a fundamental part of his program. In his long career, Bakunin was to exert from exile abroad a considerable influence on Russian radicals.

The Russian intelligentsia, like intellectuals elsewhere in Europe, reacted against the romanticism of their predecessors. They turned to a narrowly utilitarian view of art and society. All art must have a social purpose, and those bonds holding the individual tightly to the traditions of society must be smashed: parental authority, the marriage tie, the tyranny of custom. For these people, the name nihilist (a person who believes in nothing) quickly became fashionable.

In the 1860s many young Russian intellectuals went to Switzerland. Also present in Switzerland were two important Russian revolutionary thinkers, Peter Lavrov and Peter Tkachev. Lavrov (1823-1900) taught his followers that as intellectuals they owed a great debt to the Russian peasant, whose labor had enabled their ancestors to enjoy leisure and had made their own education possible. Lavrov advised the nihilist students to complete their education and then return to Russia and go among the peasants, educating them and spreading among them propaganda for an eventual, revolution of the masses. On the other hand, Tkachev (1844-1886) taught that revolution would have to come from a tightly controlled revolutionary elite, a little knot of conspirators who would seize power.

Under the influence of these teachers, especially Bakunin and Lavrov, Russian nihilists turned to a new kind of movement, called populism. Young men and women of education decided to return to Russia and live among the peasants. When a government decree in 1872 actually summoned them back, they found that a parallel movement had already begun at home. About three thousand young people now took posts as teachers, innkeepers, or store managers in the villages.

Their romantic views of the peasantry were soon dispelled, however. Suspicious of their motives, the peasants often betrayed them. The populists became conspicuous and were easily traced by the police, who arrested them. Two mass trials were held in the 1870s. After the trials those populists who remained at large decided that they needed a determined revolutionary organization. With the formation of the Land and Freedom Society in 1876, the childhood of the Russian revolutionary movement was over.

The revolutionaries had been further stimulated by Alexander II’s grant of reforms. So great had the discontent become that it is doubtful whether an’ Russian government could have proceeded fast enough to suit the radicals. Russian socialism was not yet greatly influenced by the gradualism of Marx. It was not urban but rural, not evolutionary but revolutionary, not a mass political parry but a conspiracy. The movement became more and more radical, and in 1879 those who believed in the use of conspiracy and terror separated from the others and founded a group called the People’s Will; the antiterrorists called themselves the Black Partition. The first deeply influenced Lenin’s parry; the second was an ideological ancestor of Bolshevism.

The members of the People’s Will now systematically went on a hunt for Czar Alexander II himself. They shot at him and he crawled on the ground to safety. They mined the track on which his train was traveling, and blew up his baggage train instead. They put dynamite under the dining room of the palace and exploded it, but the czar was late for dinner that night, and eleven servants were killed instead. They rented a shop on one of the streets along which he drove and tunneled under it. Finally, in March of 1881, they killed him with a handmade grenade, which also blew up the assassin.

Not all Russian intellectual life was so directly concerned with the problem of revolution and social reform. Many intellectuals preferred to work within the creative arts. Here, too, artists tended to be taken up with the kinds of issues that divided the Westerners and the Slavophiles. For example, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov had used the sounds of folk music in his compositions, and in his operatic work Modest Moussorgsky had given Russians pride in their national past.

Above all, Russian prose writers of the late nineteenth century towered above the cultural landscape. All of Europe read Alexander Pushkin, Ivan Turgenev, Anton Chekhov, Nikolai Gogol, or the poet Mikhail Lermontov (1814-1841). To non-Russian readers, two writers seemed to best express the romantic sense of despair to be found in the Russian revolutionaries.

One, Feodor Dostoevsky, had died in 1881, but his brilliant, disturbed work seemed best to represent the trend of Russian thought: compassion for all humanity, an almost frenzied desire to remake society—a mixture of socialist commitment and religious conviction that was both understandable and exotic to the West. In Crime and Punishment, The Possessed, and The Brothers Karamazov, the last completed in 1880, he had shown himself to be a giant of modern literature.

The most influential voice of the time in circles outside Russia was that of Count Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910), who had participated in the Crimean War and, in War and Peace (1865-1869), had pungently revealed the failings of the Russian nobility during the Napoleonic wars. In 1876, while writing Anna Karenina, a masterpiece of moral tragedy, he underwent what he called a conversion to a belief in Christian love and nonresistance to evil.

He shared the romantics’ view that the Russian future lay with the peasants, for urban society became inevitably corrupt and violent. He thus became a spokesman for pastoral simplicity and Christian anarchism, and he was widely read in Russia and abroad.