In a sense, nationalism was a doctrine invented in Europe in the nineteenth century to account for social, economic, and political changes that required a single descriptive term.

The notion of nationhood easily led to the assumption that humanity was divided—by divine intent, nature, or the material force of history—into nations, and that therefore the course of history was toward the self-determination of those peoples. The American Declaration of Independence had asserted such a principle, and by the mid-nineteenth century most people in western Europe appear to have assumed that the only legitimate type of government was that which carried a society toward independence.

Most commentators on nationalism argue that certain common characteristics can be identified, so that a “nation” can be objectively defined. These characteristics include a shared language, a common object of love (usually called the homeland), a shared life in a common territory under similar influences of nature and common outside political pressures, and the creation of a state of mind that strives toward a sense of homogeneity within the group.

This sense of common identity is fostered by holding to common symbols, rituals, and social conventions through a common language (or variant of it), religion, and sense of mutual interdependence. Usually the positive aspects of such a sense of group identity will be strengthened by a negative emphasis on those who lack such characteristics.

Nationalism may be fed by what some historians call “vital lies”—beliefs held to be so true and so central to a sense of identity that to question them at all is to be disloyal. Thus certain historical ideas may be untrue— even lies consciously fostered—but because of widespread belief in them, they have the vitality and thus the function of truth. Most modern societies think of their way of life as superior to others. Most peoples believe themselves chosen—whether by God or by history.

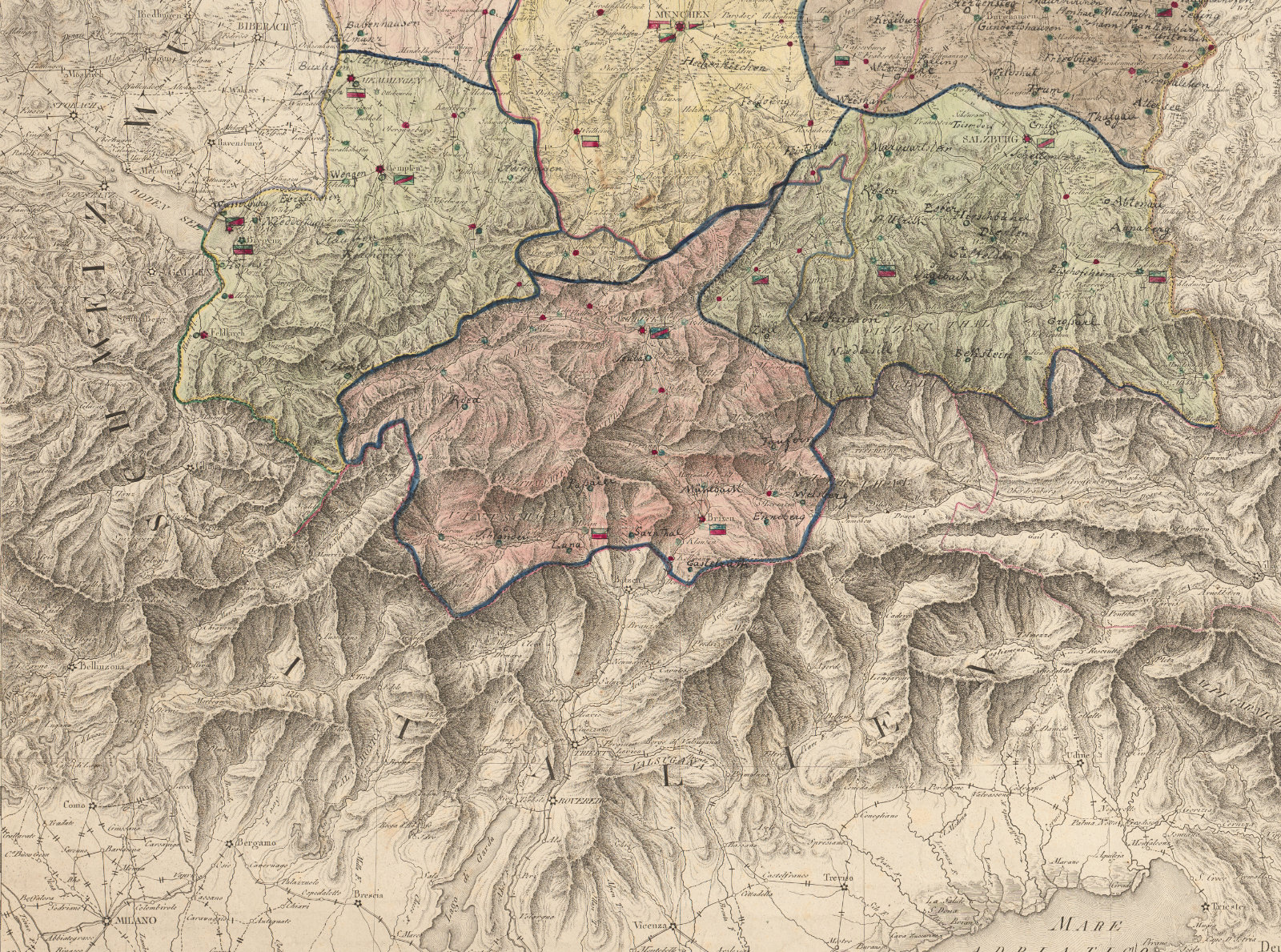

In the twentieth century such assumptions about national identity and the nation as the source of group and individual security and stability are commonplace. But what now seems natural was, in fact, unfamiliar or still emerging as part of the process of modernization in the nineteenth century. This was especially so among the many language groups of the Habsburg Empire. For the Habsburg Empire, “modernization” did not mean unification. It meant fragmentation and a trend toward representative government only in relation to divisive nationalisms, not toward new national unities.

For over sixty years, from 1848 to 1916, the German-speaking emperor Francis Joseph sat on the Habsburg throne. Immensely conscientious, he worked hard reading and signing state papers for hours every day. But he was without imagination, inflexibly old-fashioned and conservative. He was intensely pious, and his mere longevity inspired loyalty. His decisions usually came too late and conceded too little. His responsibility for the course of events is large.

Habsburg history between 1850 and 1914 divides naturally into equal portions at 1867, when the empire became the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary. After the suppression of the revolution of 1848, there was a decade of repression usually called the Bach system, from the name of the minister of the interior, Alexander Bach (1813-1893), ending in 1859 with the war against Piedmont and France. Eight years of political experimentation followed, from 1859 to 1867, punctuated by the war of 1866 with Prussia.

In 1849 all parts of the empire were for the first time unified and directly ruled from Vienna by German- speaking officials. In 1855 the state signed a concordat with the Catholic church giving clerics a greater influence in education and other fields than they had enjoyed since the reforms of Joseph II. The repressive domestic policies of the Bach period required expensive armies and policemen.

Instead of investing in railroads and industry, Austria went into debt to pursue centralization, an enlarged bureaucracy, and Germanization. These expenditures left it at a disadvantage compared with Prussia. Then during the Crimean War Francis Joseph failed to assist the Russians and kept them in fear of an attack by occupying the Danubian principalities (modern Romania). Defeat in 1859 at the hands of the French and Italians and the loss of Lombardy with its great city of Milan brought about the end of the Bach system.

War continued to threaten, and the nationalities inside the empire, especially the Magyars, could not be left in a state of perpetual discontent, which would render their troops unreliable. Several solutions were tried in an effort to create a structure that would withstand the domestic and foreign strains but that would not jeopardize the emperor’s position. Francis Joseph listened first to the nobles, who favored loose federalism, and then to the bureaucrats, who favored tight centralism. In 1860 he set up a central legislature to deal with economic and military problems. To it the provincial assemblies (diets) throughout the empire would send delegates.

All other problems were left to the provincial diets, elected by a system that worked to disfranchise the peasants. This solution, known as the October Diploma, did not satisfy the Magyar nobility of Hungary. Even so, Austrian liberals and bureaucrats felt that the October Diploma gave the Magyars too much. It seemed to them that the empire was being dismembered on behalf of the nobility, who dominated the provincial assemblies. Therefore, in 1861 the February Patent reinterpreted the Diploma, creating an even more centralized scheme. A bicameral imperial legislature took over most of the powers that the October Diploma had reserved for the provincial assemblies or diets.

Naturally, the Magyars objected to this second solution even more than to the first, and they flatly refused to participate. To the applause of the Germans in Vienna, including the liberals, Hungary returned to authoritarian rule. Czechs and Poles also eventually withdrew from the central parliaments and left only a German rump. Disturbed, the emperor suspended the February Patent and began to negotiate with the Magyars, who were represented by the intelligent and moderate Ferenc Deal( (1803-1876).

The negotiations were interrupted by the war with Prussia in 1866. The Austrian defeat at Sadowa, the expulsion of Austria from Germany, and the loss of Venetia threatened the entire Habsburg system. Clearly Austria could not risk war with any combination of Prussia, France, or Russia. Francis Joseph resumed negotiations with the Magyars. In 1867 a formula was found that was to govern and preserve the Habsburg domain down to the World War of 1914-1918.