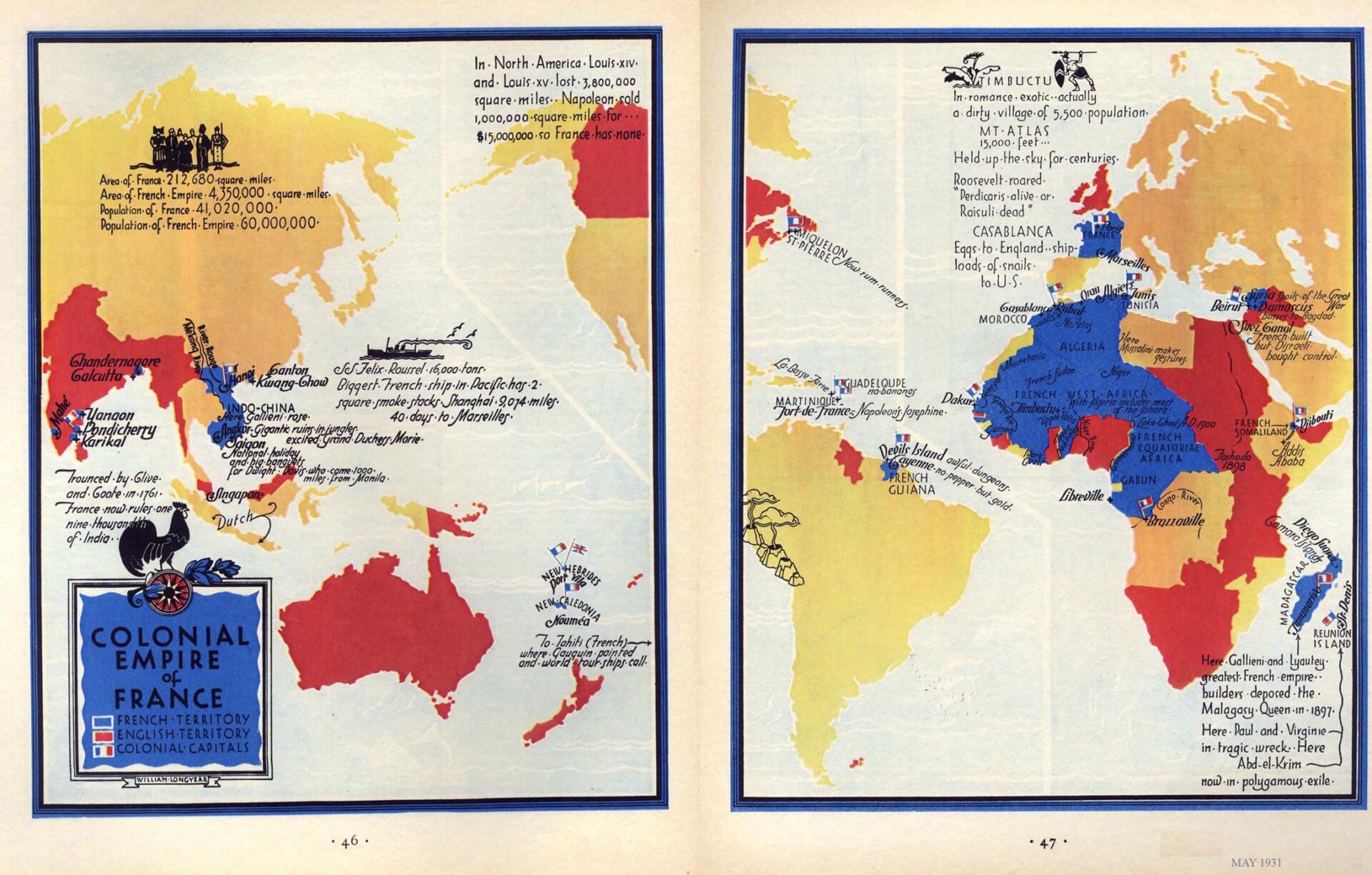

During the nineteenth century France acquired a colonial empire second in area only to that of the British. France, despite frequent revolutionary changes in government, maintained an imperialist policy that added some 50 million people and close to 3.5 million square miles to the lands under the French flag. This empire was concentrated in North, West, and Equatorial Africa, and in Indochina.

Little of this colonial empire was thought suitable for settlement by Europeans, especially since a third of it was taken up by the Sahara Desert. A major exception was French North Africa: Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco. These lands, with a typically Mediterranean climate, were inhabited chiefly by Berber and Arab peoples of Muslim faith.

Though the total indigenous population increased greatly under French rule, more than a million European colonists moved in. Mostly French, but including sizable groups of Italians and Spaniards, these colons took land from the native groups. Though they added to the total arable acreage by initiating irrigation projects and other improvements, they were hated by the native peoples.

The French spent forty years in “pacifying” the hinterland of Algiers in the face of stubborn local resistance. The French then added protectorates over Tunisia to the east (1881) and over Morocco to the west (1912). In 1904 Britain gave the French a free hand in Morocco as compensation for their exclusion from Egypt. In Algeria and Tunisia the French hoped to assimilate Africans into French civilization. They hoped to create an empire of “one hundred million Frenchmen,” more than half of them overseas, and to draw on abundant local manpower to fill up the ranks of the republic’s armies.

In the main, assimilation proved difficult and was only partly achieved. Militarily, the policy worked out pretty much as the French had hoped; black troops from Senegal and goums (Moroccan cavalry serving under French or Algerian Muslim officers) gained a reputation as tough fighters. The French, bequeathed their language and laws to part of the indigenous elite. Under the Third Republic they made Algeria politically a part of France itself, organizing it into three departments each with representatives to the Chamber of Deputies; the franchise was open to the relatively small group of Europeanized Algerians as well as to colons.

In Morocco the French took a somewhat different tack. They sought, in part successfully, to open the area to French business and to the international tourist trade. But even by World War I it was apparent that economies based in large measure on tourism were chronically dependent and unstable, so that a diversified economic base was badly needed.

In 1912 the French colonial administrator Marshal Hubert Lyautey (1854-1934) began to apply a “splash of oil” policy—that is, he pacified certain key centers by establishing firm working relations with the local population, and then hoped to let pacification spread over the surface of Morocco like a splash of oil on water. The sultan and his feudal subordinates were maintained in Morocco by the French, left relatively free to carry on traditional functions but stripped of real power.

Tunisia, like Morocco, was formally a regency. Because Tunisia was small and easily pacified, assimilation was pursued more intensively there than in other French possessions.

By 1914 the French had been very successful in the partition of Africa. In 1914 France had nearly as many inhabitants in Africa as in the home territories (about 39 million). Yet outside of North Africa and certain coastal towns where their administration and business enterprises were concentrated, the French had not achieved much progress toward assimilating or Westernizing their vast districts.

In Asia, the French took over lands that came to be called French Indochina, which included two rich, rice-growing deltas around Hanoi in the north and Saigon in the south, inhabited by peoples culturally and ethnically related to the Chinese. They also included Cambodia, culturally related to Siam, and the remote mountain lands of Laos.

In the process the French made many enemies: they fought the Vietnamese in 1883, forcing the status of a protectorate on the court at Hue in 1883; fought a war with China in 1884, since Peking claimed Vietnam as its own protectorate; assumed power in Cambodia in the face of a popular revolt; and claimed Laos by promoting a coup that threw off Siamese over- lordship in 1893.

The French sought to assimilate the local elite class, and they turned Saigon into a French-style city of broad boulevards. They brought substantial material progress in medicine and hygiene, communications, roads, education, industry, and agriculture. They also applied to proud societies European notions of hierarchy. Nationalist movements, nourished by educated local leaders who held jobs of less dignity and authority than they believed should be theirs, rose in strength as the years went on.