Even more than the writers and preachers of the Renaissance, its artists displayed an extraordinary range of originality in their interests and talents. They found patrons both among the princes of the church and among merchant princes, condottieri, and secular rulers. They took as subjects their own patrons and the pagan gods and heroes of antiquity, as well as Christ, the Virgin, and the saints. Although their income was often meager, they enjoyed increasing status both as technicians and as creative personalities.

The artists liberated painting and sculpture from subordination to architecture. The statues, carvings, altarpieces, and stained glass contributing so much to Romanesque and Gothic churches had usually been only parts of a larger whole. In the Renaissance the number of freestanding pictures and sculptures steadily increased.

Important advances in painting came with the further development of chiaroscuro, stressing contrasts of light and shade, and with the growing use of perspective. In the early Renaissance painters worked in fresco or tempera; in fresco they applied pigments to the wet plaster of a wall, and the painters had to work swiftly before the plaster dried; in tempera they mixed pigments with a sizing, often of eggs, which allowed them to work after the plaster had dried but gave the end product a muddy look. Oil paints overcame the deficiencies of fresco and tempera by permitting leisurely, delicate work and ensuring clearer and more permanent colors.

Without Leonardo, Michelangelo, and other Italian artists of genius, the Renaissance could never have become one of the great ages in the history of art. In sculpture it rivaled the golden centuries of Greece; in painting it transformed a rather limited medium into a dazzling new instrument. It is no wonder that historians often use Italian designations for these centuries; trecento, quattrocento, and cinquecento (literally, “300s,” “400s,” and “500s,” abbreviated references to the 1300s, 1400s and 1500s).

Florence was the artistic capital of the Renaissance in Italy. Lorenzo the Magnificent subsidized the painter Sandro Botticelli (c. 1444-1510) as well as the humanists of the Platonic Academy. Court painters were commonplace in other states, both in Italy and elsewhere. In Milan, II Moro made Leonardo da Vinci in effect his minister of fine arts and director of public works; after Sforza’s fortunes collapsed, Leonardo found new patrons in Cesare Borgia, the pope, and the French kings Louis XII and Francis I.

The mixture of worldly and religious motives among patrons also characterized the works they commissioned. Artists applied equal skill to scenes from classical mythology, to portraits of their secular contemporaries, and to such religious subjects as the Madonna, the Nativity, and the Crucifixion. Often the sacred and the secular could be found in the same picture; for example, in the Last Judgment, in the Arena Chapel, Giotto portrayed Scrovegni, who had commissioned the work, on the same scale as the saints.

Patronage, like art, was a complex matter. Many patrons were lay men and women who wanted a religious painting for their house; many were corporate and ecclesiastical, such as religious brotherhoods who wished a painting on the theme of the saint after whom their church was named; many were corporate and secular, such as the wool guild, who might wish to illustrate a specific theme; many were individual and ecclesiastical, such as the popes, archbishops, and bishops of the church; and there was always the state, as when the Florentine government commissioned Michelangelo to make a bronze David (as opposed to his marble David). Patrons could and did dictate the trends in themes, the use of materials, the placement of finished objects. Thus commerce, prestige, a sense of place, the desire to honor an occasion, and social customs all shaped art and were in turn shaped by the artists’ responses to their commissions.

Renaissance artists at first painted classical and pagan subjects like Jupiter or Venus as just another lord and lady of the chivalric class. Later they restored the sense of historical appropriateness by using classical settings and painting the figures in the nude; at the same time, however, they also created an otherworldly quality. When Botticelli was commissioned by the Medici to do The Birth of Venus (1485), he made the goddess, emerging full grown from a seashell, more ethereal than sensual, and he placed the figures in the arrangement usual for the baptism of Christ. In Primavera (c. 1478), Botticelli’s allegory of spring, the chief figures—Mercury, Venus, the Three Graces, Flora (bedecked with blossoms), and Spring herself (wafted in by the West Wind)—are all youthful, delicate, and serene.

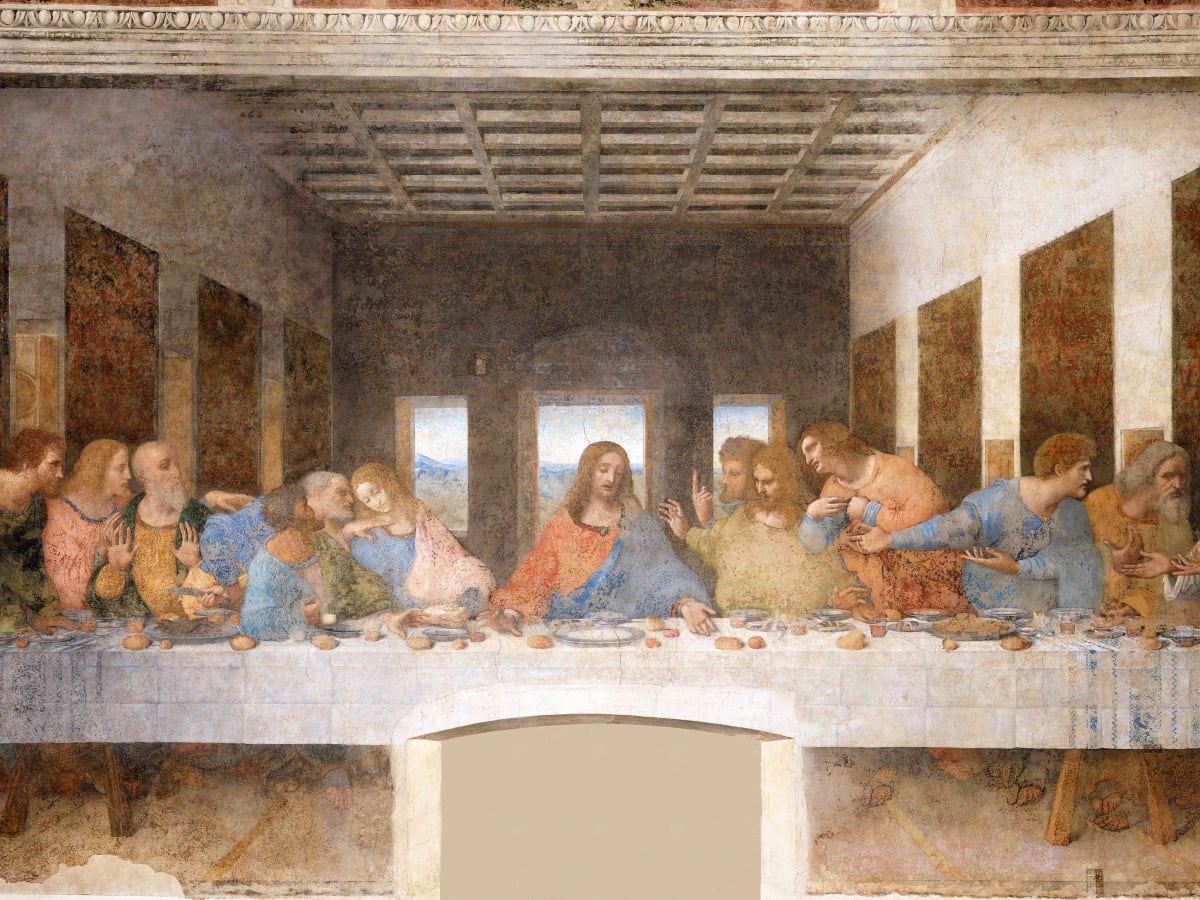

Leonardo da Vinci completed relatively few pictures, since his scientific activities consumed much of his energy. Moreover, his celebrated fresco, The Last Supper (1495— 1498), began to deteriorate during his own lifetime because the mold on the damp monastery wall in Milan destroyed the clarity of the oil pigments he used. Luckily, Leonardo’s talent and his extraordinary range of interests can also be studied in his drawings and notebooks. The drawings include preliminary sketches of paintings, fanciful war machines, and doodles, along with realistic portrayals of human embryos and of deformed suffering individuals.

In composing The Last Supper Leonardo departed dramatically from previous interpretations. He divided the apostles into four groups of three men around the central figure of Christ. His second departure was to choose the tense moment when Jesus announced the coming betrayal, and to place Judas among the apostles, relying on facial expression and bodily posture to convey the guilt of the one and the consternation of the others.

Michelangelo Buonarotti (1475-1564), though best known as a sculptor, ranks among the immortals of painting as a result of the frescoes he executed for the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican. He covered a huge area with 343 separate figures and spent four years working almost alone, assisted only by a plasterer and a color mixer, painting on his back atop a scaffold, sometimes not even descending for his night’s rest.

He began over the chapel entrance with The Drunkenness of Noah and ended over the altar with The Creation. God appears repeatedly. Hovering over the waters, he is benign; giving life to the motionless Adam or directing Eve to arise, he is gently commanding; creating the sun and the moon, he is the formidable, all-powerful deity.

Both Michelangelo and Leonardo had received their artistic training in Florence. Titian (1477-1576) was identified with Venice, and the rich reds and purples that are his hallmark exemplify the flamboyance and pageantry of that city. At the start he was engaged to do frescoes for the Venetian headquarters of German merchants, and he went on to portraits of rich merchants, Madonnas, altarpieces for churches and monasteries, and a great battle scene for the palace of the doge. He was offered commissions by half the despots of Italy and crowned heads of Europe.