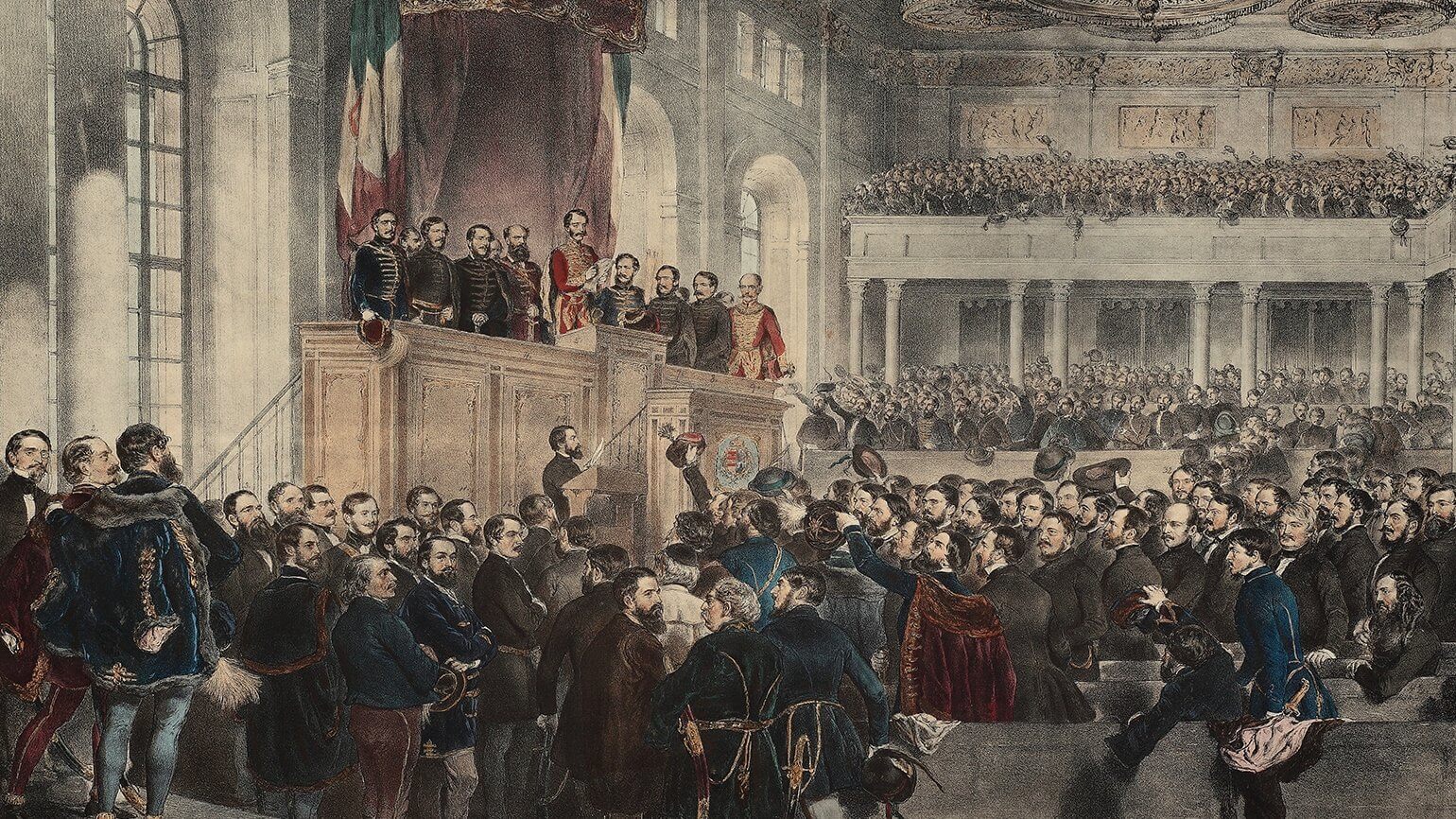

This formula was the Ausgleich, or “compromise,” which created the unique dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary. The Hungarian constitution of 1848 was restored, and the entire empire was reorganized as a strict partnership.

Austria and Hungary were united in the person of the emperor, who was always to be a Catholic and a legitimate Habsburg, and who was to be crowned king of Hungary in Budapest. For foreign policy, military affairs, and finance, the two states had joint ministers appointed by the emperor. A customs union, subject to renewal every ten years, united them. Every ten years the quota of common expenditure to be borne by each partner was to be renegotiated.

A unique body, the “delegations,” made up of sixty members from the Austrian parliament and sixty members from the Hungarian parliament, meeting alternately in Vienna and in Budapest, was to decide on the common budget, which had to be ratified by the full parliaments of both countries. The delegations also had supervisory authority over the three joint ministers and might summon them to account for their activities.

In practice, however, the delegations seldom met and were almost never consulted on questions of policy. The system favored Hungary, which had 40 percent of the population but never paid more than a third of the expenses. Every ten years, therefore, when the quota of expenses and the customs union needed joint consideration, a new crisis arose.

One overwhelming problem remained common to both halves of the monarchy: that of the national minorities who had not received their autonomy. Some of these minorities (Czechs, Poles, Ruthenes) were largely in Austria; others (Slovaks, Romanians) were largely in Hungary; the rest (Croats, Serbs, Slovenes) were in both states. These nationalities were at different stages of national self-consciousness.

Some were subject to pressures and manipulation from fellow nationals living outside the dual monarchy. All had some leaders who urged compromise and conciliation with the dominant Austrians and Magyars, as well as others who advocated resistance and even revolution. The result was a chronic and often unpredictable instability in the dual monarchy.

The Austrian constitution of 1867 provided that all nationalities should enjoy equal rights and guaranteed that each might use its own language in education, administration, and public life. And in 1868 the Hungarians passed a law that allowed the minorities to conduct local government in their own language, to hold the chief posts in the counties where they predominated, and to have their own schools. But in practice the minority nationalities suffered discrimination and persecution.