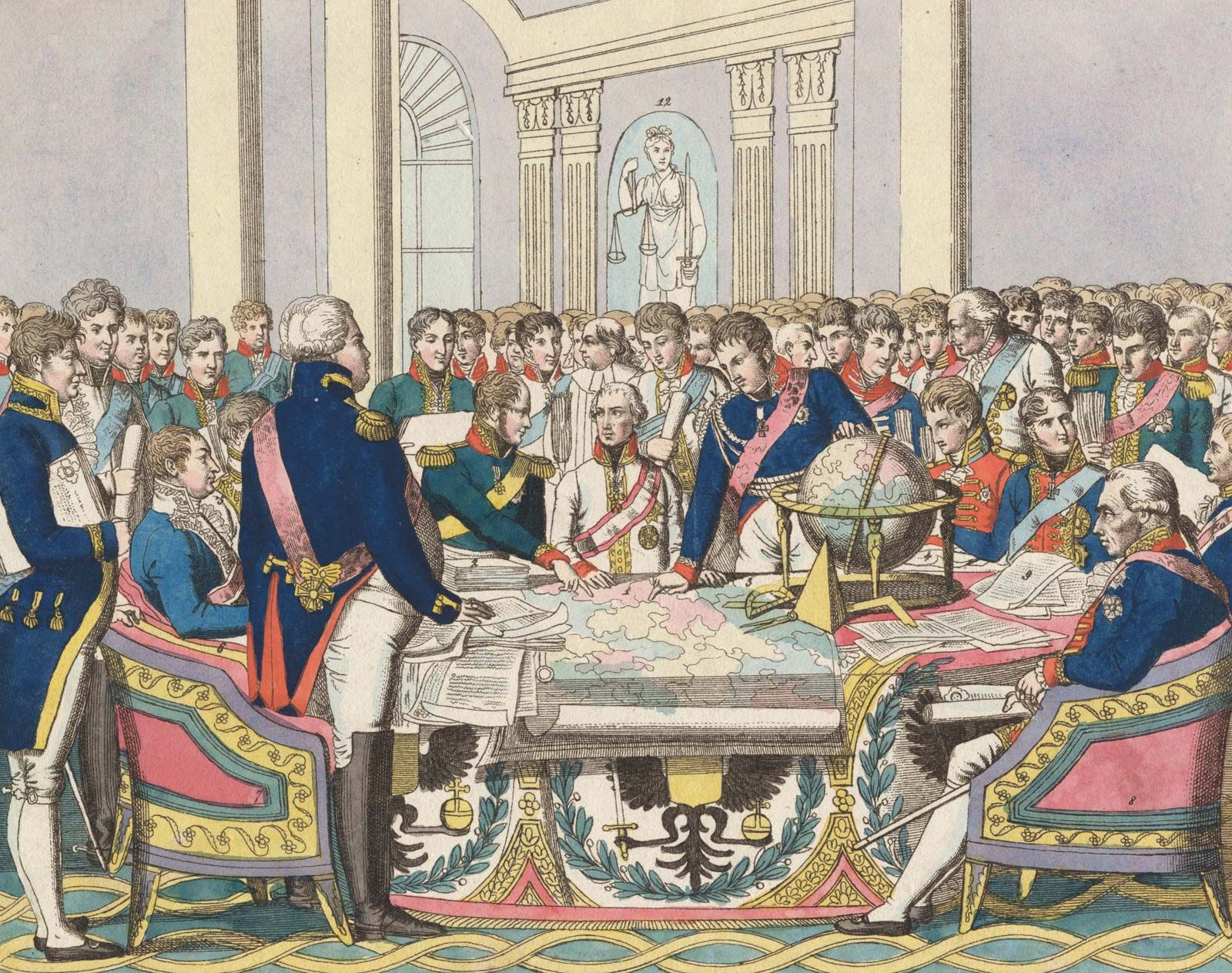

In 1814 and 1815 Metternich was host to the Congress of Vienna, which approached its task of rebuilding Europe with conservative deliberateness. For the larger part of a year, the diplomats indulged in balls and banquets, concerts and hunting parties. “The Congress dances,” quipped an observer, “but it does not march.” Actually, the brilliant social life distracted hangers-on while the important diplomats settled matters in private.

Four men made most of the major decisions at Vienna: Metternich; Czar Alexander I; Viscount Castlereagh (1769-1822), the British foreign secretary; and Charles Maurice de Talleyrand (1754-1838), the French foreign minister. Castlereagh was at Vienna, he said, “not to collect trophies, but to bring the world back to peaceful habits.” The best way to do this, he believed, was to restore the balance of power and keep the major states, including France, from becoming either too strong or too weak.

At Vienna, Talleyrand scored the greatest success of his long career. Originally a worldly bishop of the Old Regime, he had in succession rallied to the Revolution in 1789, become one of the very few bishops to support the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, served as Napoleon’s foreign minister, and then, while still holding office, intrigued against him after 1807. This adaptable diplomat soon maneuvered himself into the inner circle at Vienna. He was particularly adept in exploiting the differences that divided the victors.

To these differences Alexander I contributed greatly. Alexander’s Polish policy nearly disrupted the Congress. He proposed a partial restoration of eighteenth-century Poland, with himself as its monarch; Austria and Prussia would lose their Polish lands. Alexander won the support of Prussia by backing its demands for the annexation of Saxony. Metternich, however, did not want Prussia to make such a substantial gain. Moreover, both Metternich and Castlereagh disliked the prospect of a large, Russian- dominated Poland.

Talleyrand joined Metternich and Castlereagh in threatening both Prussia and Russia with war unless they moderated their demands. The threat produced an immediate settlement. Alexander obtained Poland but agreed to reduce its size and to allow Prussia and Austria to keep part of their gains from the partitions. Prussia took about half of Saxony, while the king of Saxony was allowed to keep the rest.

Once the Saxon-Polish question was out of the way, the Congress was able to turn to other important dynastic and territorial questions. According to what Talleyrand christened “the sacred principle of legitimacy,” thrones and frontiers were to be reestablished as they had existed in 1789. In practice, however, legitimacy was ignored almost as often as it was applied, since the diplomats realized that they could not undo all the changes brought about by the Revolution and Napoleon.

Although they sanctioned the return of the Bourbons to the thrones of France, Spain, and Naples in the name of legitimacy, they did not attempt to resurrect the republic of Venice or to revive all the hundreds of German states that had vanished since 1789. In Germany the Congress provided for thirty-nine states grouped in a weak confederation. The Diet, chief organ of the German Confederation, was to be a council of diplomats from sovereign states rather than a representative national assembly. Its most important members were to be Prussia and Austria, for the German- speaking provinces of the Habsburg realm were considered part of Germany.

The land exchanges were complex and often cynical, with little or no regard for the wishes of the people. Prussia, besides annexing part of Saxony, added the Napoleonic kingdom of Westphalia to its scattered lands in western Germany, creating the imposing Rhine Province.

Austria lost Belgium, which was incorporated into the kingdom of the Netherlands to strengthen the northern buffer against France. But Austria recovered the eastern Adriatic shore and the old Habsburg possession of Lombardy, to which Venetia was now joined. The Congress of Vienna restored the Bourbon kingdom of Naples, the States of the Church, and, on their northern flank, the grand duchy of Tuscany. The kingdom of Piedmont- Sardinia acquired Genoa as a buttress against France.

Another buttress was established in the republic of Switzerland, now independent again and slightly enlarged. The Congress confirmed the earlier transfer of Finland from Sweden to Russia and compensated Sweden by the transfer of Norway from the rule of Denmark to that of Sweden. Finally, Great Britain received the strategic Mediterranean islands of Malta and the Ionians at the mouth of the Adriatic Sea and, outside Europe, the former Dutch colonies of Ceylon and the Cape of Good Hope, plus some minor French outposts.

France at first was given its boundaries of 1792, which included minor territorial acquisitions made during the early days of the Revolution. Then came Napoleon’s escape from Elba and the Hundred Days. The final settlement reached after Waterloo assigned France the frontiers of 1790, substantially those of the Old Regime plus Avignon.

To quarantine any possible new French aggression, Castlereagh conceived the policy of strengthening France’s neighbors. Thus, to the north the French faced the Belgians and the Dutch combined in the single kingdom of the Netherlands; on the northeast they faced the Rhine Province of Prussia; and on the east, the expanded states of Switzerland and Piedmont. In the Quadruple Alliance, signed in November 1815, the four allies—Britain, Prussia, Austria, and Russia—agreed to use force, if necessary, to preserve the Vienna settlement.

The Holy Alliance, signed in September 1815, was dedicated to the proposition that “the policy of the powers . . . ought to be guided by the sublime truths taught by the eternal religion of God our Savior.” However, neither the Holy Alliance nor the Quadruple Alliance fulfilled the expectations of their architects. At the first meeting of the Quadruple Alliance, in 1818, the allies agreed to withdraw their occupation forces from France, which had paid its indemnity. At the next meeting of the allies, two years later, Metternich and Castlereagh would find themselves ranged on opposite sides on the issue of putting down revolutions under international auspices.

For these revolutions of 1820-1821 the Congress of Vienna was itself partly to blame, through its attempt to suppress liberal and nationalist aspirations. Yet as major international settlements go, that of Vienna was a sound one. There was to be no war involving several powers until the Crimean conflict of the 1850s, and no major war embroiling the whole of Europe until 1914.

Seldom have victors treated a defeated aggressor with the wisdom and generosity displayed in 1815. Most of the leading diplomats at Vienna could have said with Castlereagh that they acted “to bring the world back to peaceful habits.”