The Greeks are the first ancient society with which modern society feels an immediate affinity. We can identify with Greek art, Greek politics, Greek curiosity, and the Greek sense of history. The polis, roughly translated as the city-state, was the prevailing social and political unit of ancient Greece. Athens and Sparta were the two most significant poleis.

Sparta was a conservative military oligarchy ruled jointly by two kings and a council of elders. It had an excellent army, but its society was highly regimented. Sparta produced little of artistic or cultural importance.

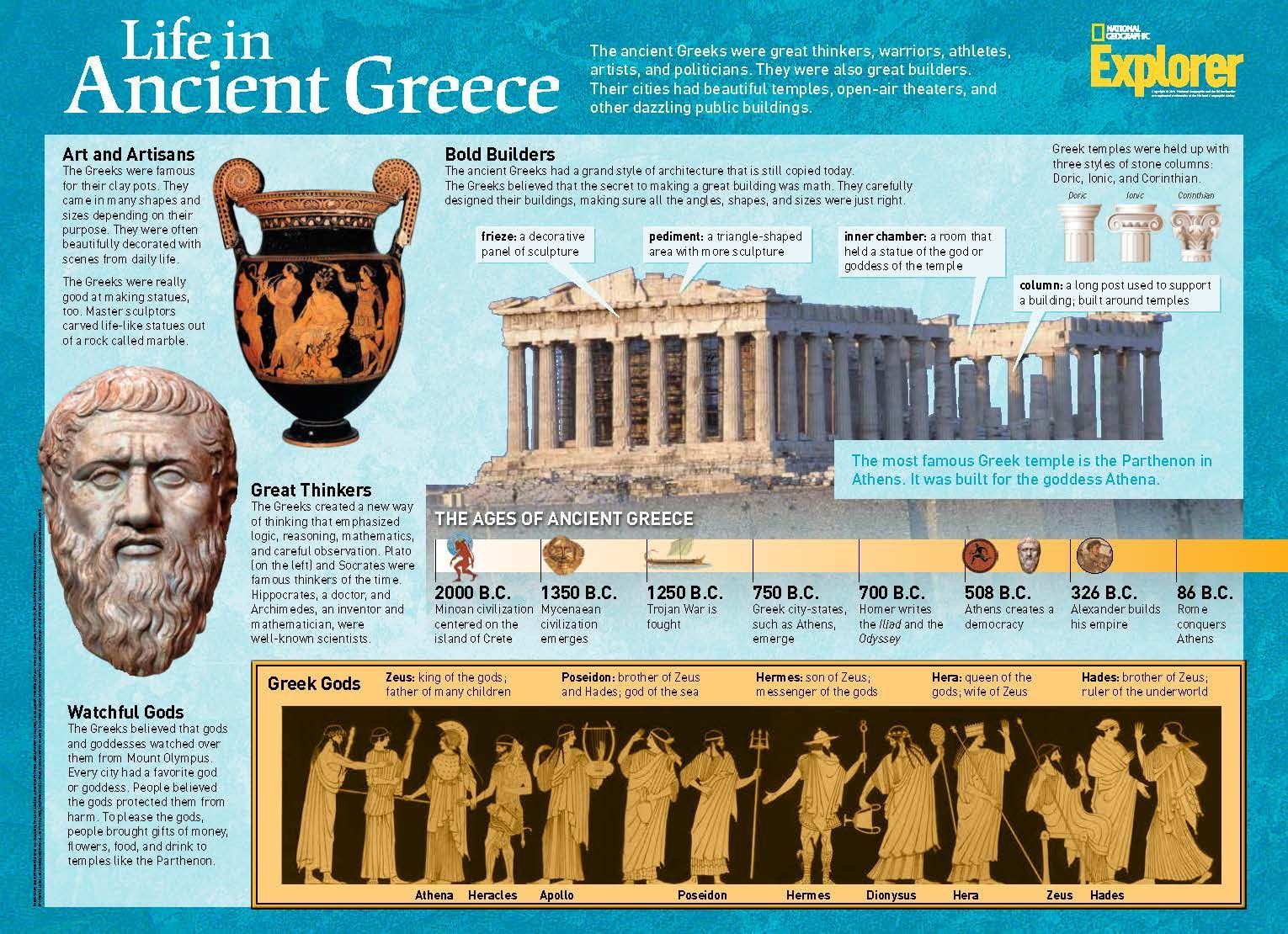

Athens progressed from an old-fashioned, aristocratic tribal state in the eighth century B.C. to a tyranny and then to a democracy by the fifth century B.C. Among the most important leaders of this transition from a state based on ties of kinship to one based on political citizenship were the lawgivers Draco and Solon, the tyrant Pisistratus, and the reformer Cleisthenes.

Athens depended, as did all Greek states, upon the systematic exploitation of slaves. Although influential in the home, women were also a subject group. Fathers and husbands determined the extent of their personal freedom.

By the fifth century B.C., the Persian Empire, which had subjugated all of the Near East, including the Greek cities of Asia Minor (Ionia), was extending its rule into northern Greece. Two Persian invasions of Greece were defeated: by the Athenians at Marathon (490 B.C.) and by united Greek forces at the battles of Salamis (480) and Plataea (479).

After the defeat of Persia, Athens and Sparta were rivals for the leadership of Greece. The Athenian Empire that emerged from the Persian defeat was brought to its zenith by Pericles, who beautified Athens and advanced the democratization of its constitution.

Rivalry between Athens and Sparta led to the Peloponnesian Wars (460-445, 431-404 B.C.), in which Athens was eventually defeated after a plague ravaged the city and a great expedition to Sicily met with disaster.

Thereafter, neither Sparta, nor Thebes, nor a revived Athens, could successfully lead Greece. In the 330s Greek disunity led to domination by Philip, king of Macedon, a semi-Greek kingdom to the north.

Philip’s son Alexander, the Great, invaded and conquered the Persian Empire in 334-327 B.C. Alexander’s conquests spread Greek colonists and culture from Egypt to the borders of India.

After Alexander’s death in 323 three main successor dynasties emerged, each founded by one of his generals: the Ptolemies in Egypt, the Seleucids in Syria and Mesopotamia, and the Antigonids in Macedon and Asia Minor. All of these states were eventually absorbed by Rome.

Greek religion was centered upon the worship of the Olympian gods. Greek drama developed out of a festival at Athens in honor of the god Dionysus. The chief Greek playwrights who have survived are the tragedians Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides and the comic writers Aristophanes and Menander. The principal Greek historians whose work has come down to us are Herodotus, who wrote about the Persian Wars; Thucydides, the historian of the Peloponnesian Wars; and Polybius, whose subject was the rise of Roman power.

The Greeks attributed many of the workings of nature to natural rather than to supernatural causes. In medicine, geography, geometry, physics, and astronomy, their achievements still command respect.

Greek philosophy had its roots in natural science and in the tendency of science to question established beliefs and traditions. Socrates taught that the truth could be found only in a never-ending debate, a process of question and answer-the famous “Socratic method.” His pupil Plato’s theory of Ideas is one of the great wellsprings of Western thought. Plato’s pupil Aristotle was the first to use scientific method, classifying living things, beliefs, and systems of government. The Epicurean and Stoic schools of philosophy sought to show people how to live contented lives in a troubled world. The influence of Greek art and architecture on Western civilization is incalculable.