The creation of a unified Italy and Germany altered the balance of power in Europe in the 1860s and 1870s. Nationalism, imperialism, great-power alliances, and public opinion—influenced by newspapers and photos—helped fuel tensions. By the early 1900s the Triple Alliance and the Triple Entente had taken shape. A naval arms race between Germany and Britain as well as diplomatic and military crises in Morocco, the Balkans, and elsewhere contributed to an uneasy peace.

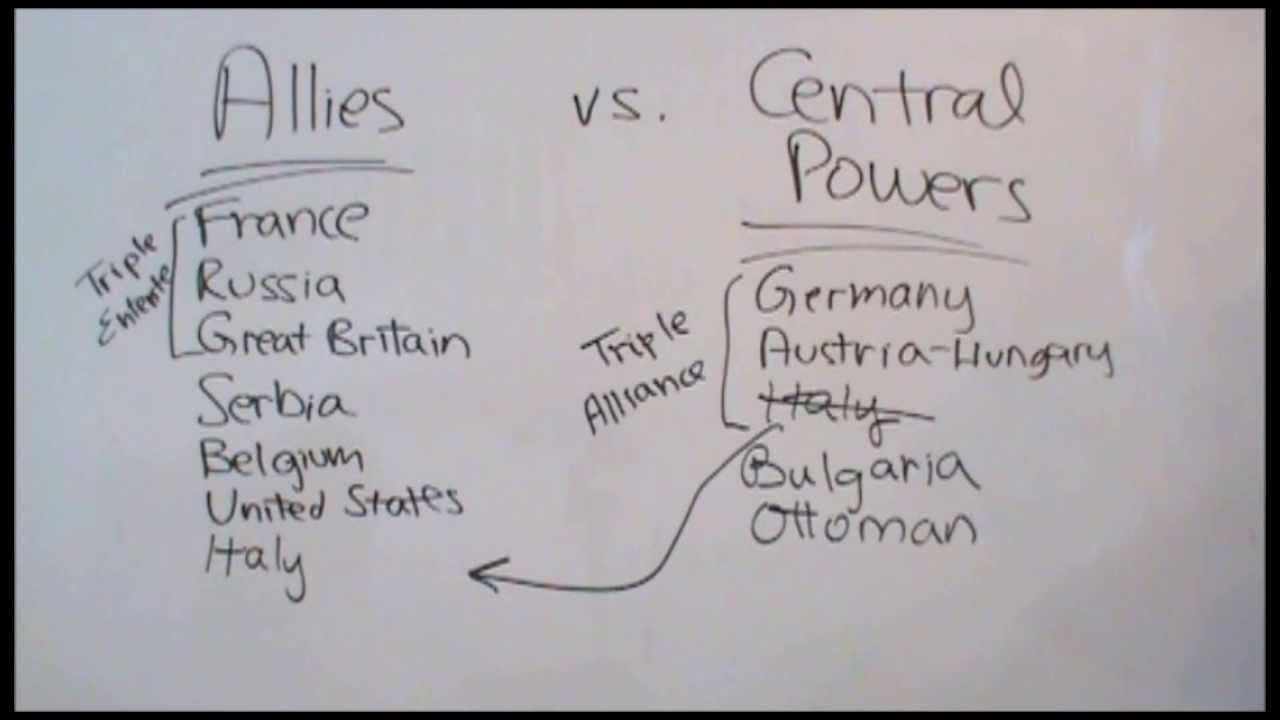

The assassination of Habsburg archduke Francis Ferdinand, heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary, set off a crisis that led to war. Austria took a strong stand against Serbia, holding it responsible for the assassination. When Serbia rejected demands, Austria declared war. Germany, Russia, France, and Britain aided their respective allies. Italy declared its neutrality but later joined the Allies. Other European nations were drawn into the conflict. By 1917 repeated violations of neutral shipping brought the United States into the war.

The Schlieffen plan for German armies to eliminate France before turning to the Russian front did not succeed. German soldiers were pinned down on the western front, where a stalemate existed throughout much of the war. Millions more were tied down on the eastern front until 1917, when Russia withdrew from the war. The war was fought on other fronts in the Near East, East Africa, and the Far East, as well as on the oceans of the world. The last German offensive in the spring of 1918 could not be sustained, and by that summer the Allies were advancing on the western front. On November 11, 1918, a defeated Germany signed an armistice.

On the home fronts, wartime economic planning anticipated the regulated economies of the postwar era. Both sides waged virulent propaganda warfare. War contributed to changes in social life and in moral codes.

President Wilson’s Fourteen Points embodied the hopes for peace. However, conflicting aims among the Allies over reparations, punishment of Germany, and territorial settlements soon dashed liberal hopes for peace. Russia and the Central Powers were not represented at Versailles as the Big Four—Wilson, Lloyd George, Clemenceau, and Orlando—bargained, com- promised, and established new nations. An international organization, the League of Nations, was set up with a consultative assembly, but it did not fulfill the hopes of its early supporters.

In the end, the United States refused to ratify the treaty. France, weakened by the war, had its way with reparations, while Germany, still potentially the strongest nation in Europe, reluctantly accepted the treaty.

Strikes and shortages of bread as well as huge losses in the war prepared the way for revolution in Russia in 1917. From the outset, the provisional government and soviets were in conflict. When the moderate provisional government failed to meet crises at home and abroad, Lenin, who had returned to Russia from exile, called for a program that appealed to the Russian people.

In November 1917 the Bolsheviks seized power in Petrograd. The Bolshevik revolution brought great changes to Russia, although the new regime displayed much continuity with old Russia—an autocratic dictator, an elite of bureaucrats and managers, secret police, and Russian nationalism.