Nationalism and the accompanying shifts in the balance of power both influenced and were profoundly influenced by public opinion, often shaped by the public press.

Throughout western Europe and in the United States a jingoistic press, often intent on increasing circulation, competed for “news,” and not all papers were careful to separate the verifiable from the rumor, the emotional atrocity story (even when true) from the background account that would explain the context for the emotion.

Technology made printing far cheaper than it had ever been. In 1711 the highly influential English paper The Spectator sold two thousand copies a day, and there was only a handful of effective competitors; in 1916 a Paris-based newspaper sold over 2 million copies a day, and there were hundreds of other newspapers. This revolution in communicating the printed word had taken place in the nineteenth century.

The Times of London began to use steam presses in 1814, producing copies four times as fast as before. In Britain and France and later in central Europe, the railway made a national press possible— the papers of Paris could be read anywhere in France the next day. After the 1840s the invention of the telegraph encouraged the creation of news services and the use of foreign correspondents, so that the same story might appear throughout the nation though in different papers.

When Richard Hoe (1812-1886), a New Yorker, invented a rotary press in 1847 that could produce twenty thousand sheets an hour, the modern newspaper was born. Linotype and, from the 1880s, monotype machines were also used to set books, and by 1914 there had been a massive leap in the sale of all reading matter. This in turn gave rise to greater censorship in some societies, and everywhere to an awareness that the printed word could be manipulated to political purposes.

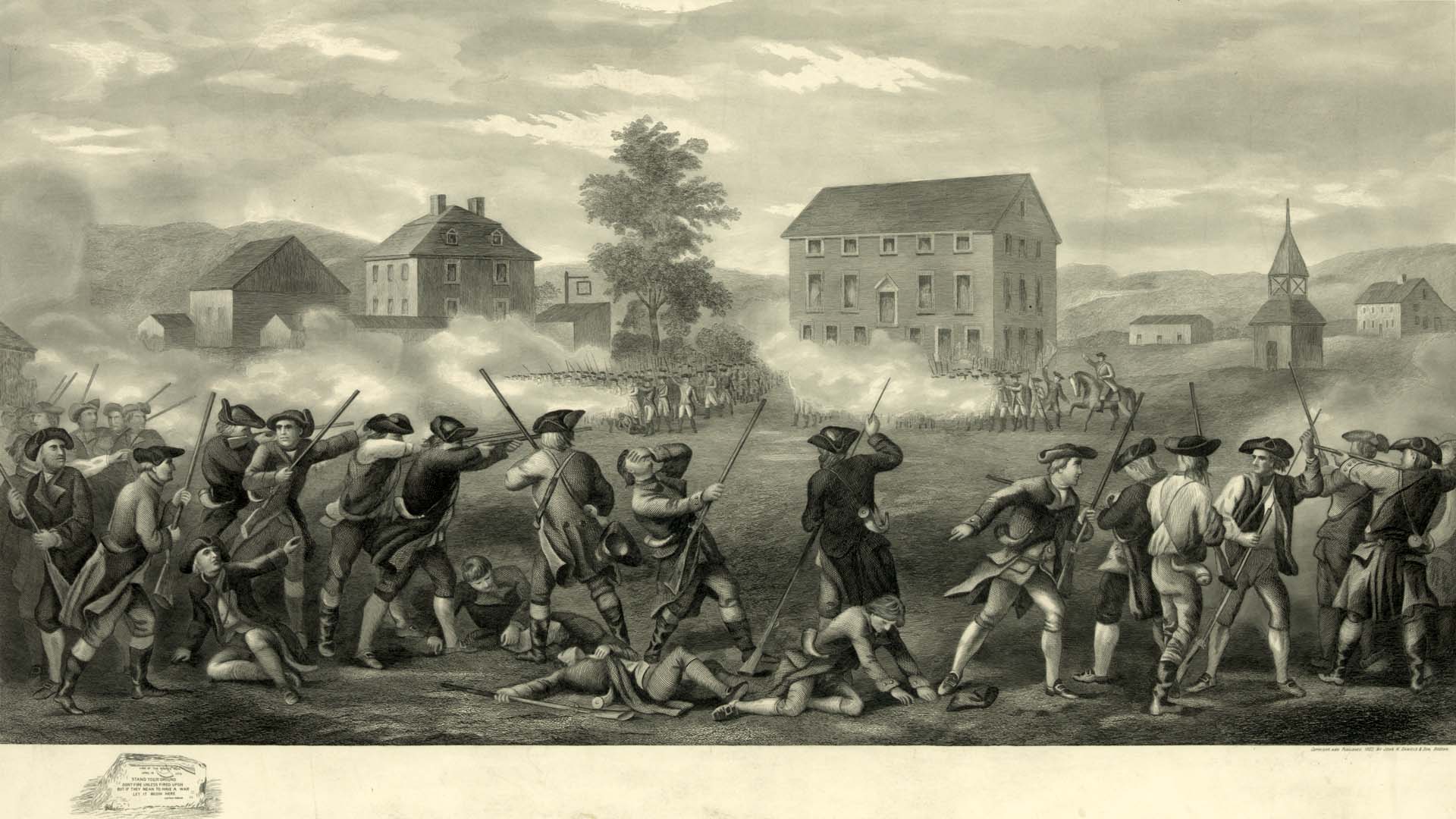

The printed word was supplemented by illustrations. The battle map was introduced to the public in the American Civil War. After 1839 daguerreotypes began to replace painting as a means of conveying reality. In the 1880s, mass-produced cameras became available. A simple box camera, the Kodak, was invented in 1888, and with the concurrent commercialization of the halftone screen, newspaper pictures became commonplace.

Newspapers became more important in political life. In Britain Alfred Harmsworth (1865-1922), in France Charles Dupuy (1844-1919), and in the United States two competitors, Joseph Pulitzer (1847-1911) and William Randolph Hearst (1863-1951), brought all the elements together to create mass journalism. The two Americans worked to promote war with Spain in 1898, and all these papers supported the establishment and jingoist views.

The introduction of universal peacetime conscription by the Continental powers further stimulated the introduction of compulsory universal elementary education, and later of universal manhood suffrage. These led to a further growth in the number of readers, to greater political content in the press, and to the quest for technological innovation in rapid typesetting. One could, by 1900, genuinely speak of “public opinion” as a force in world affairs.

Thus the outbreak of war in 1914 saw in each belligerent nation broad public support of the government. Men marched off to war convinced that war was necessary. Even the socialists supported the war. Yet, public opinion might as easily have been led against war, had an increasingly complex alliance system not cut off national options and individual leaders not chosen the course they did.

For example, in the hectic five weeks after the assassination at Sarajevo, the German kaiser, William II, belatedly tried to avoid a general war. But in the decisive years between 1888 and 1914 he had been an aggressive leader of patriotic expansion, encouraging German youth to believe that while their enemies were numerically superior, Germany’s spiritual qualities would more than compensate for brute strength.

German ambitions and German fears had produced an intense hatred of Britain. At first few English returned this hate, but as the expensive race between Britain and Germany in naval armaments continued and as German wares progressively undersold British wares in Europe, in North and South America, and in Asia, the British began to worry about their prosperity and leadership. The British were worried about their obsolescent industrial plants and their apparent inability to produce goods as efficiently as the Germans; they were critical of their commercial failures abroad and some feared their increasingly stodgy self-satisfaction. There was, in effect, a crisis of imperialism in British domestic politics.

In France prewar opinions on international politics ran the gamut. A large socialist left was committed to pacifism and to an international general strike of workers at the threat of actual war. However, an embittered group of patriots wanted revanche or revenge for the defeat of 1870. The revanchists organized patriotic societies and edited patriotic journals.

The French, like the British, had supported movements for international peace—the Red Cross, conferences at the Hague in 1899 and 1907, and various abortive initiatives by the inter- national labor movement. But French diplomats continued to preserve and strengthen the system of alliances against Germany, and in July 1914 it was clear that France was ready for war.