The Middle Ages saw considerable achievement in natural science. Modern scholars have revised downward the reputation of the Oxford Franciscan Roger Bacon (c. 1214-1294) as a lone, heroic devotee of “true” experimental methods; but they have revised upward such reputations as those of Adelard of Bath (twelfth century), who was a pioneer in the study of Arab science; William of Conches (twelfth century), whose greatly improved cosmology was cited for its particularly elegant clarity; and Robert Grossteste (c. 1175-1253) at Oxford, who clearly did employ experimental methods. In many ways modern Western science goes back at least to the thirteenth century.

First, real progress took place in the technologies that underlie modern science—in agriculture, in mining and metallurgy, and in the industrial arts generally. Accurate clockwork, optical instruments, and the compass all emerged from the later Middle Ages. Even such sports as falconry and such dubious subjects as astrology and alchemy helped lay the foundations of modern science.

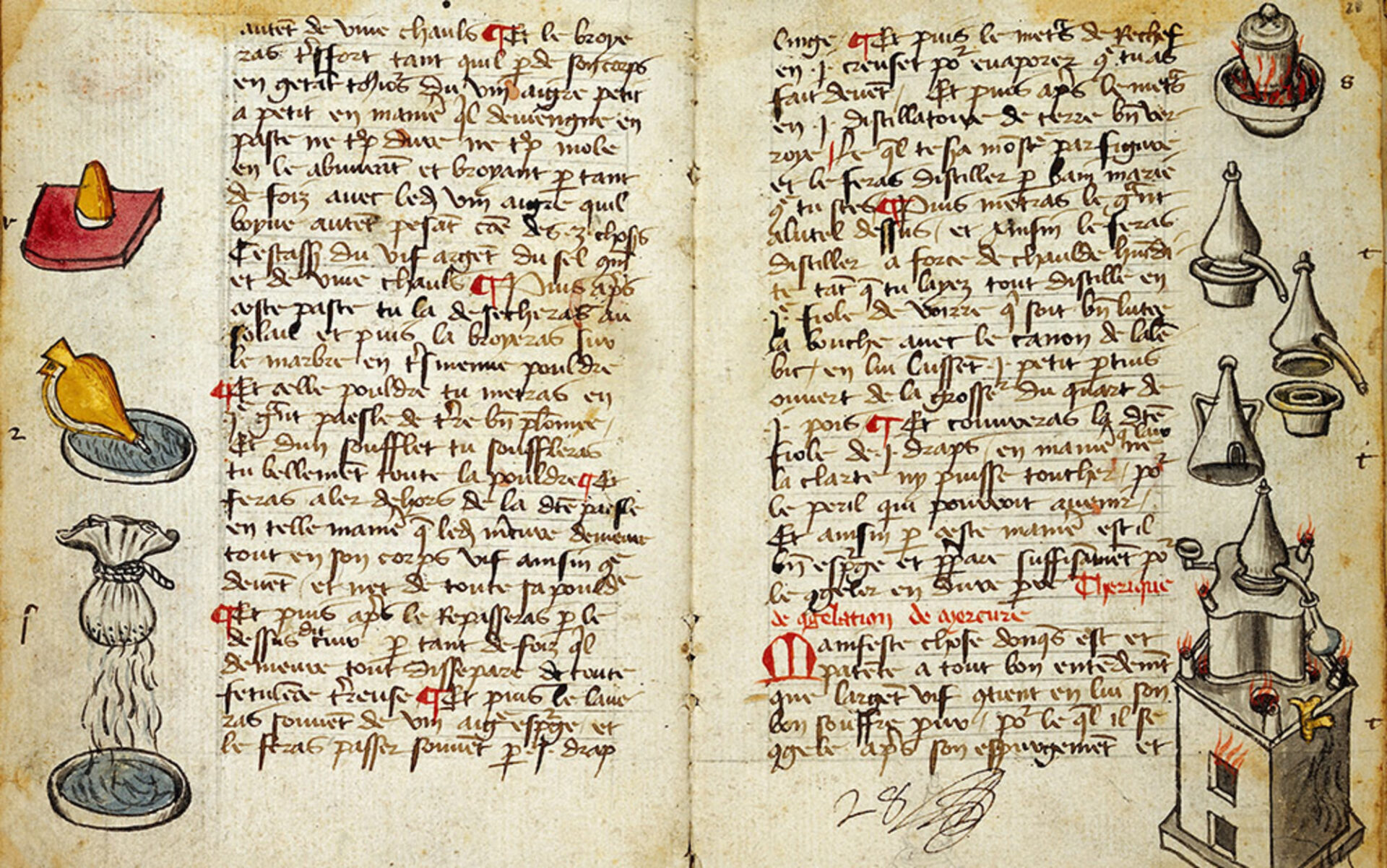

The breeding and training of falcons taught close observation of the birds’ behavior; astrology involved close observation of the heavens and complicated calculations; alchemy the identification and rough classification of elements and compounds. Second, mathematics was pursued throughout the period. Through the Arabs, medieval Europeans learned Arabic numerals and the symbol for zero—a small thing, but one without which the modern world could hardly get along.

Finally, and most important, the discipline of Scholasticism formed a trained scholarly community that was accustomed to a rigorous intellectual discipline. Natural science uses deduction as well as induction, and early modern science inherited from the deductive Scholasticism of the Middle Ages the meticulous care, patience, and logical rigor without which all the inductive accumulation of facts would be of little use to scientists.