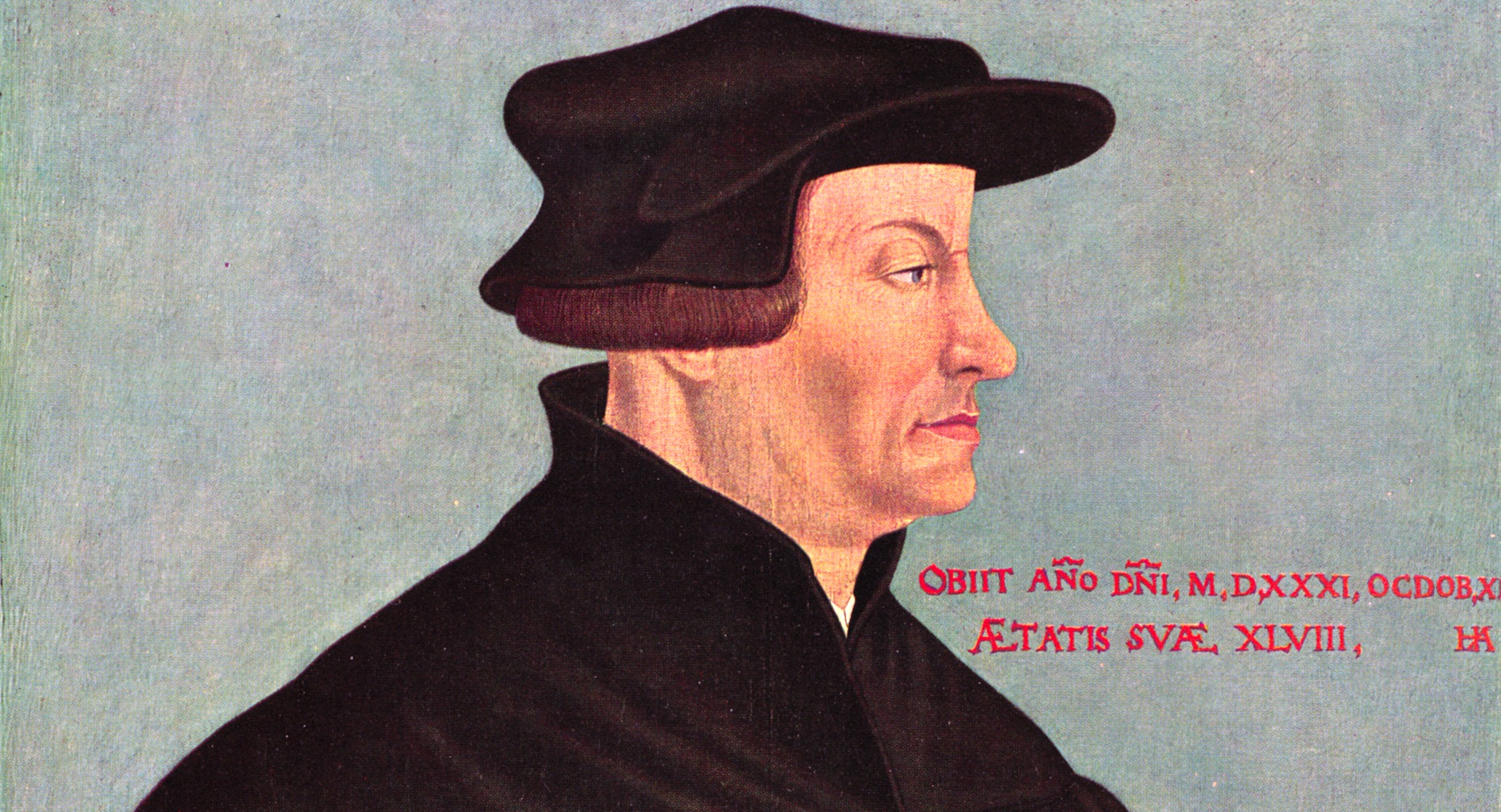

There were many other figures who attacked the Church of Rome. Some of these, like Thomas Miintzer (c. 1470— 1525), strongly opposed Luther’s views. But among the many founders of what came to be known as Protestantism, the first in sequence was Ulrich Zwingli (1484– 1531), the first in importance John Calvin (1509-1564).

At about the time of Luther’s revolt, Zwingli, a German, began a quieter reform in the Swiss city of Zurich that soon spread to Bern and Basel in Switzerland and to Augsburg and other south German cities. Zwingli’s reform extended and deepened some of the fundamental theological and moral concepts of Protestantism.

A scholarly humanist trained in the tradition of Erasmus, Zwingli sought to combat what seemed to him the perversion of primitive Christianity that endowed the consecrated priest with a miraculous power not shared by the laity. He preached a community discipline that would promote righteous living. This discipline would arise from the social conscience of enlightened and emancipated people led by their pastors.

Zwingli believed in a personal God, powerful and real, yet far above the petty world of sense experience. He was more hostile to the sacraments than Luther was. He distrusted belief in saints and the use of images, incense, and candles, which he thought likely to lead to superstition among the ignorant. In the early 1520s Zwingli began to abolish the Catholic liturgy, making the sermon and a responsive reading the core of the service and simplifying the church building into an undecorated hall, in which a simple communion table replaced the elevated Catholic altar.

A good example of Zwingli’s attitude is his view of communion. The Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation held that by the miraculous power of Christ the elements in the Eucharist, the bread and wine, became in substance the body and blood of Christ, although their “accidents,” their chemical makeup, remained those of bread and wine.

In rejecting transubstantiation, Luther put forward a difficult doctrine called consubstantiation, which held that in communion the body and blood were mysteriously present in the bread and wine. Zwingli, however, adopted what became the usual Protestant position: that partaking of the elements in communion commemorated Christ’s last supper in a purely symbolic way.