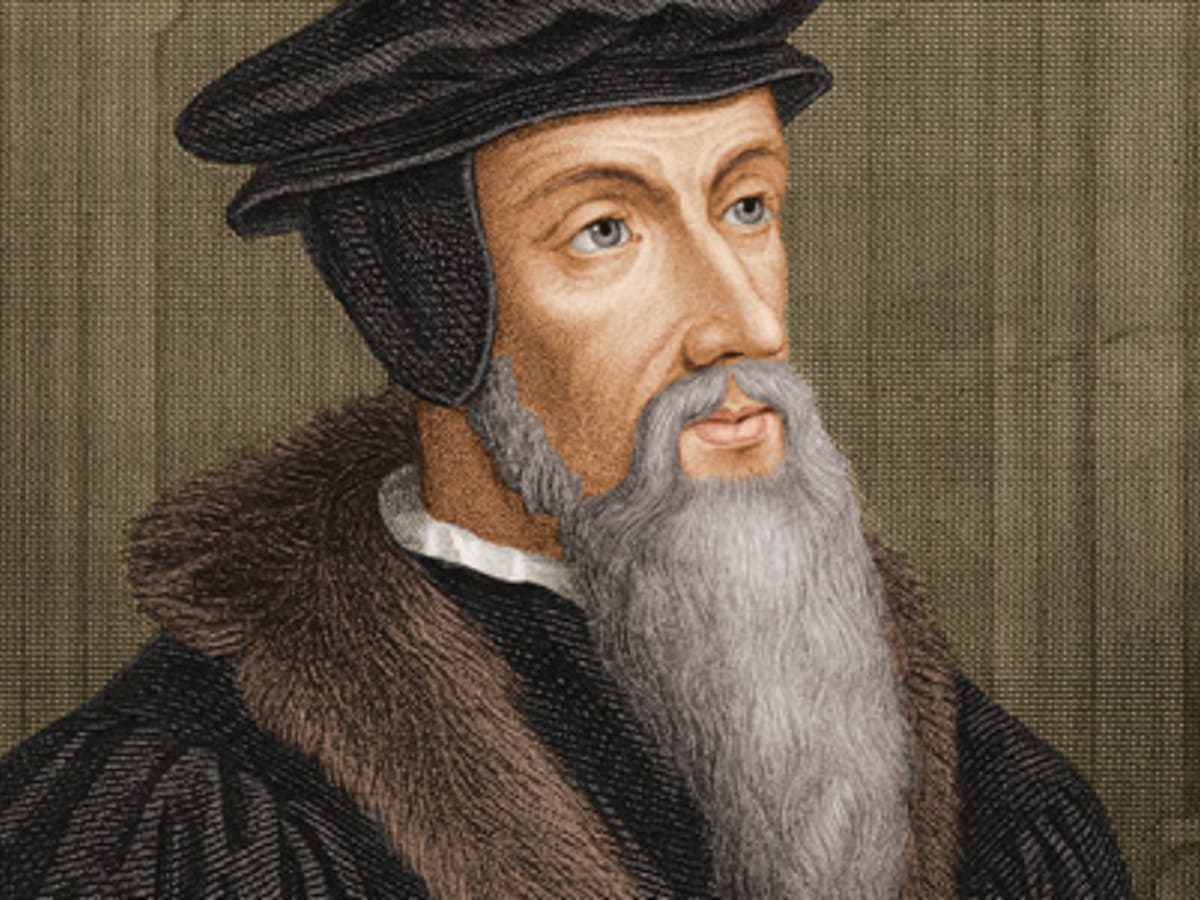

Another Swiss city ripe for Protestant domination was Geneva. A new religious and political regime developed there under the leadership of the French-born Jean Chauvin—John Calvin. Calvin shaped the Protestant movement as a faith and a way of life in a manner that gave it a more broadly European basis. Both Calvin and Zwingli worked their reforms through and with the town councils of their respective cities. Once again lay piety, a growing literacy, and a desire for local control aided the reformers.

Calvin’s career had many parallels with Luther’s. Both men had ambitious fathers who had made their way up the economic and social ladder; both gave their sons superior educations; the young Calvin studied theology and, to please his father, law. Both young men experienced spiritual crises, Calvin’s resulting in his conversion to Protestantism in his early twenties.

In temperament, however, the two men differed markedly. In contrast to the emotional, outgoing Luther, Calvin was a very private man, an intellectual, austere, very certain of his convictions and of his vocation to convert others to them, vet filled with anxieties over the formlessness of any life that would be attempted without doctrine.

In 1536 Calvin published in Basel his Institutes of the Christian Religion, which laid the doctrinal foundation for a Protestantism that, like Zwingli’s, broke completely with Catholic church organization and ritual. Calvin’s system had a logical rigor and completeness that gave it great conviction. Also in 1536 Calvin passed through Geneva and was invited to remain.

There he set about organizing his City of God and made Geneva a magnet for Protestant refugees from many parts of Europe who were indoctrinated in Calvin’s faith and then returned to promote his teachings in their own countries. Within a generation or two Calvinism had spread to Scotland, where it was led by a great preacher and organizer, John Knox (c. 1510-1572); then to England, whence it was brought to Plymouth in New England; to parts of the Rhineland; to the Low Countries, where it was to play a major role in the Dutch revolt against Spanish rule; and to Bohemia, Hungary, and Poland.

In France, where concern over the worldliness of the Catholic church was very great, Calvin’s ideas also found ready acceptance. Soon there were organized Calvinist churches, called Huguenot, especially in the southwest. But King Francis I was not eager to challenge Rome. In 1516 he had signed with the pope the Concordat of Bologna, which increased royal authority over the Gallican church in exchange for certain revenues that went to Rome.

In the mid-sixteenth century few people could conceive of the possibility of subjects of the same ruler professing and practicing differing religious faiths. In France, therefore, Protestantism had to fight not for toleration, but to succeed Catholicism as the established faith. The attempt failed, but only after wars of religion lasting for a generation in the later 1500s (see Chapter 13) and after Calvinism had left its mark on French thought.