After the death of St. Louis, the French monarchy experienced a trend toward centralization and consolidation of administrative functions. This tendency began with the reign of St. Louis’s grandson, Philip IV (r. 1285-1314). Called “the Fair,” Philip ruthlessly pushed the royal power; the towns, the nobles, and the church suffered further invasions of their rights by his agents. Against the excesses of Philip the Fair, the medieval checks against tyranny failed to operate.

His humiliation of the papacy helped to end the idea of the Christian commonwealth. The vastly increased gens du roi, “the king’s men,” used propaganda, lies, and trickery to undermine all authority except that of the king. Members of the parlement now traveled to the remotest regions of France, bringing royal justice to all parts of the king’s own domain and more and more taking over the machinery of justice in the great lordships.

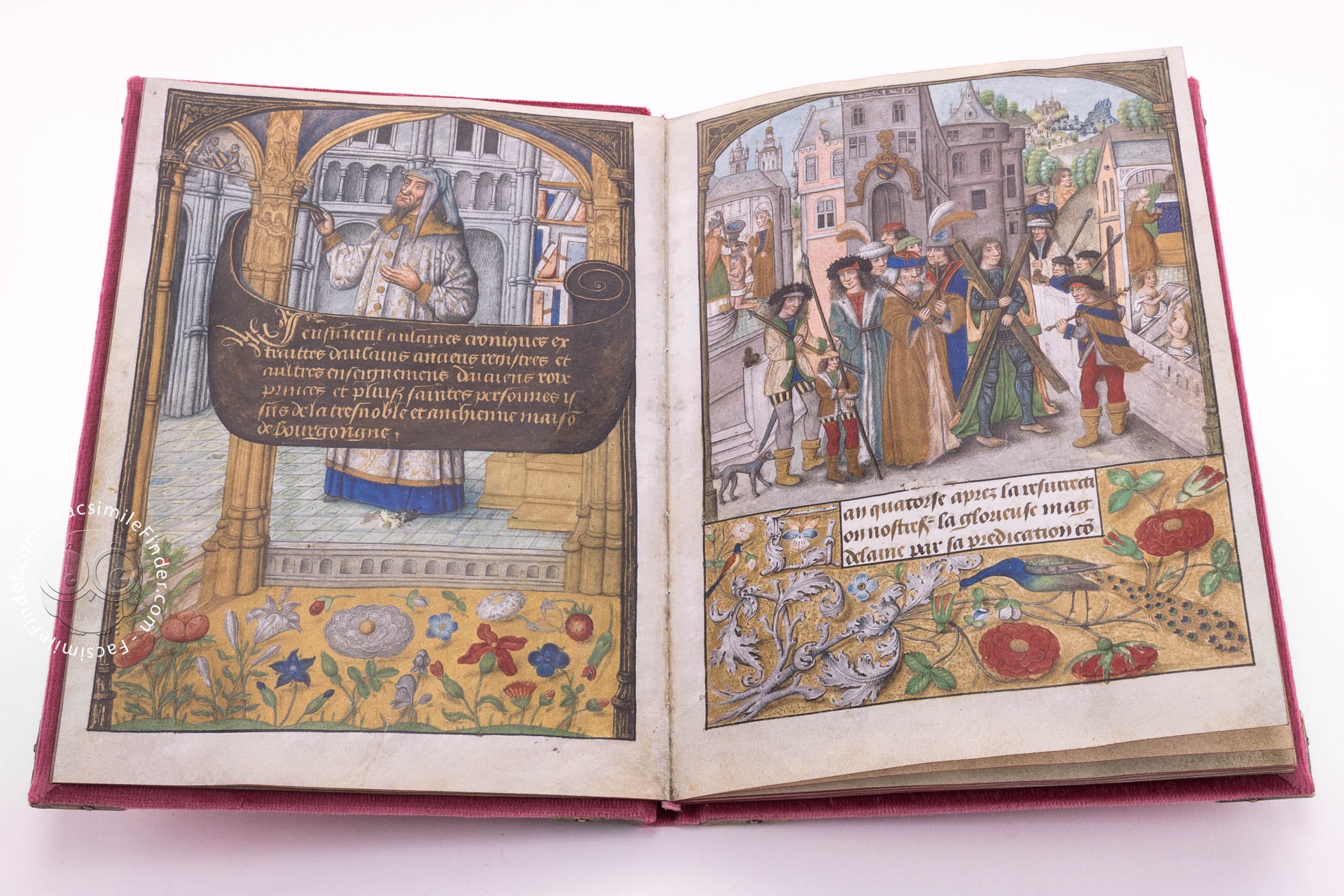

In the same period, the most intimate advisers of the king in the curia regis became differentiated as the “narrow” or “secret,” while the larger group of advisers, consisting of the remaining lords and high clerics, was called the “full council.” In 1302, apparently for the first time, representatives of the towns attended a meeting of this larger council. There began the long transition to a new kind of assembly, the Estates General. An estate is a social class; traditionally, the clergy is considered the first estate, the nobility the second, and the townspeople the third. When all three estates are present, an assembly is therefore an Estates General.

War with England and Flanders kept Philip pressed for cash during much of his reign. He summoned the estates to explain his need for money and to obtain their approval for his proceeding to raise it. Since medieval lords felt that no action was proper unless it was customary,whenever the king wanted to do anything new he had to try to make it seem like something old.

Philip tried all the known ways of getting money. One of the most effective was to demand military service of a man and then permit him to buy himself off. Forced loans, debasement of coinage, additional customs dues, and royal levies on commercial transactions also added to the royal income.

Although it was need for money for purely local problems that lay behind the most famous episode of Philip’s reign—his fierce quarrel with the papacy—its importance and the significance of its outcome had a major impact on the medieval world. In his papal opponent, Boniface VIII (r. 1294-1303), Philip was tangling with a fit successor to Gregory VII and Innocent III. A Roman aristocrat and already an old man when elected pope, Boniface suffered from a malady that kept him in great pain and probably partly accounted for his undoubted bad temper and fierce language.

Philip claimed the right to tax the clergy for the defense of France in his wars against England; the English monarch was taxing the clergy in his French possessions. Boniface issued an edict (known as a bull from the papal seal, or bulla, on it) declaring that kings lacked the right to tax clerics; Philip slapped an embargo on exports from France of precious metals, jewelry, and currency, which severely threatened the elaborate financial system of the papacy. The pope retreated, saying in 1297 that in an emergency the king of France could tax the clergy without papal consent, and that the king would decide when an emergency had arisen.

But a new quarrel arose in 1301. When Philip ordered Boniface’s legate to Paris arrested, tried, and convicted of heresy and treason, he asked for papal approval of the sentence. But Boniface flatly refused and declared that when a ruler was wicked, the pope might take a hand in the temporal affairs of that realm. The meeting of the Estates General in 1302 backed Philip.

Boniface pushed his claims still further in the famous bull Unam sanctam, which declared that it was necessary for salvation for every person throughout the world to be subject to the pope. This was the single strongest statement made concerning the authority of the church over the state.

When he also threatened to excommunicate the king, Philip issued a series of extreme charges against Boniface and sent a gang of thugs to kidnap him. They burst into the papal presence at the Italian town of Anagni and threatened the pope brutally, but did not dare put through their plan to seize him. Nonetheless, Boniface, who was over eighty, died not long after this humiliation.

In 1305 Philip obtained the election of a French pope, Clement V (r. 1305-1314), who went to Avignon, on the border between France and the Holy Roman Empire, and made this city his permanent residence. Thus began the “Babylonian captivity” of the papacy at Avignon (1309-1377). Clement issued bulls reversing Boniface’s claims, lifted the sentence of excommunication from Boniface’s attackers, and praised Philip the Fair for his piety. For three quarters of a century the papacy in Avignon was seen as a tool of the French monarchy.

Just before Philip died in 1314, the towns joined with the lords in protest against the king’s having raised money for a war in Flanders and then made peace instead of fighting. Louis X (r. 1314-1316) calmed the unrest by revoking the aid, returning some of the money, and making scapegoats of the more unpopular bureaucrats. He also issued a series of charters to several of the great vassals that confirmed their liberties.

But taxation was still thought of as inseparably connected with military service, and military service was an unquestioned feudal right of the king. So the king was still free to declare a military emergency, to summon his vassals to fight, and then to commute the service for money. For this reason the charters of Louis X did not effectively halt the advance of royal power.